Electric scooters, known locally as “електрически тротинетки” or trottinettes, have rapidly transformed urban mobility in Bulgaria in recent years. What began as a novelty has become a common sight on the streets of Sofia, Plovdiv, Varna, and other cities. Shared e-scooter services launched in the capital around 2019 and quickly gained popularity across all age groups (inyourpocket.com). On August 22, 2019, Lime – one of the world’s largest micromobility companies – deployed over 100 scooters in central Sofia, marking the city’s first major foray into e-scooter sharing. Within weeks, competitors followed suit; Bird (another US-based operator) launched in Sofia soon after, partnering with local company BRUM. A Bulgarian startup, Hobo, also rolled out its own e-scooter fleet by September 2019 (trendingtopics.eu), demonstrating the local enthusiasm for this trend.

By the early 2020s, the e-scooter phenomenon had firmly taken root. Sofia’s streets are now buzzing with privately owned scooters and app-based rentals alike. City officials estimated that by 2022, there were over 10,000 electric scooters in Sofia, including roughly 2,000 units offered by three main rental operators, novinite.com. Other urban centers have joined in: the Black Sea cities of Varna and Burgas see seasonal scooter use (especially in summer tourist months), and in 2023, the company Bolt (known for ride-hailing) launched an e-scooter service in Plovdiv, deploying 300 scooters with plans to expand further (micromobility.io). Bolt was already operating in Sofia, Varna, and Burgas prior to that, signalling that micromobility is not limited to the capital. This rapid adoption in multiple cities underscores how Bulgaria has embraced e-scooters as a modern mobility solution, offering a convenient way to zip through traffic, bridge “last mile” gaps in public transit, and enjoy urban sightseeing.

We Talk About

- Major Cities Embrace Micromobility

- Recent Issues: Injuries, Nuisance, and Social Costs

- Key Facts and Statistics in Bulgaria’s E-Scooter Boom

- Companies Operating in Bulgaria: Local and International Players

- Current E-Scooter Regulations in Bulgaria

- What Bulgarian Regulations Lack (Compared to Other Countries)

- Economic and Socio-Economic Impact

- Comparison with Other Countries: Regulation and Integration

- Why Bulgaria’s Regulatory Approach Lags or Differs

- Possible Recommendations for Improving Bulgaria’s E-Scooter Situation

- Final Words

- Sources

Major Cities Embrace Micromobility

Sofia led the e-scooter wave in Bulgaria. The city’s youthful tech-savvy population and chronic traffic congestion created ripe conditions for micromobility. Lime’s arrival in 2019 was quickly met with curiosity and demand – hundreds of Sofians tried the bright green scooters in the first days. Bird’s entry (with 15 minutes of free ride promos) further spurred interest. Meanwhile, local entrepreneurs saw an opportunity: Hobo, founded by two Bulgarians after experiencing scooters abroad, brought in a test fleet and coordinated with Sofia Municipality on regulations. They chose sturdy models (by U.S. manufacturer Acton) designed for rough urban terrain and introduced competitive pricing (BGN 1.60 unlock + 0.20 per minute) to undercut international rivals (trendingtopics.eu). Within months, Sofia had multiple brands of scooters on its streets, and usage soared. Riders praise the ability to cover 2–3 km distances much faster than walking, without waiting for a bus or tram. Tourists also find them a fun way to explore Sofia’s parks and landmarks. By late 2022, the City Council chairman noted the “rapid increase in the number of scooters” as “logical and expected” for a modern city, given their role in reducing traffic and pollution.

Plovdiv, Bulgaria’s second-largest city, was somewhat later to the trend but is catching up fast. In mid-2023, Bolt officially launched e-scooter rentals in Plovdiv, initially with 300 scooters spread around key areas. The service targeted both daily commuters and the city’s many students and tourists. Plovdiv’s historic old town with its cobbled streets poses challenges, but scooters have become popular along the flatter, modern parts of the city. Following Bolt’s entry, other providers signaled interest in Plovdiv’s market, seeing demand beyond Sofia. Varna and Burgas, on the Black Sea coast, have also seen e-scooter deployments. Bolt operates in these cities, and during summer months, the scooters are especially visible along seafront promenades and downtown areas, catering to beach-goers and young people out for leisure rides. Even smaller cities and tourist resorts have experimented with trottinettes, though on a more limited scale. The overall trend is clear: from capital city boulevards to coastal boardwalks, e-scooters have become ingrained in Bulgaria’s urban landscape.

The Allure and Benefits of E-Scooters

Why have trottinettes caught on so quickly in Bulgaria? Several factors explain their appeal. First, convenience and speed: stand-up e-scooters can weave through congested traffic and often cut travel times for short trips. In Sofia, where driving a car even for a 2 km city trip can be slow due to jams or scarce parking, hopping on an e-scooter is an attractive alternative. A user simply locates a nearby scooter via smartphone, unlocks it, and zips off – bypassing both traffic and the hunt for a parking spot. Many young professionals and students use scooters to cover the “last mile” from a metro or bus stop to their final destination, or for quick errands around town.

Second, affordability contributes to their popularity. Riding a shared scooter is cheaper than taking a taxi and often comparable to public transport for short hops. For example, Lime’s rates in Sofia launched at about 1.50 BGN (€0.77) to unlock + 0.30 BGN (€0.15) per minute. A 10-minute ride (covering roughly 2–3 kilometers) thus costs around 4.5 BGN (€2.30). This is roughly the price of two transit tickets or significantly less than a taxi fare for the same distance. Local startup Hobo set its pricing even lower, with BGN 0.80 unlock + BGN 0.20 per minute to entice cost-conscious users. Shareascoot, a Bulgarian service offering seated electric mopeds, advertises rates of 5.90 BGN for the first 10 minutes and 0.39 BGN per minute thereafter, making day-long rentals (24 hours for 59 BGN) feasible for tourists or day trips (shareascoot.bg). These price points, while not trivial for daily use, make e-scooters an accessible treat for occasional trips or as a supplement to commuting. Furthermore, many operators periodically offer promo codes or free unlocks, further boosting usage, especially among young riders.

Another oft-touted benefit is environmental friendliness. E-scooter companies market their services as “eco-friendly and sustainable”, highlighting that the vehicles are 100% electric with 0% tailpipe emissions (shareascoot.bg). In a country where air pollution and car emissions are concerns in big cities, the prospect of replacing car trips with zero-emission scooters is appealing. Indeed, city officials in Sofia have noted that scooters can be an “important factor in reducing air pollution, carbon emissions and traffic congestion” (novinite.com). Every scooter ride potentially means one less car on the road. Additionally, e-scooters are quiet, helping reduce noise pollution in busy urban centers. While the true environmental impact of shared scooters has been debated (considering production, battery charging, and van collection operations), newer industry practices are improving their green credentials. For instance, companies like Lime and Bolt have introduced scooters with swappable batteries (so that only batteries are retrieved for charging, rather than the whole scooter, reducing van mileage) and durable designs that extend scooter lifespan to multiple years. Over time, these improvements can lower the life-cycle carbon footprint of each scooter ride.

Finally, there’s a simple reason: e-scooters are fun. Many users describe riding a trottinette as an enjoyable experience – “explore the city with a smile on your face” as Shareascoot puts it (shareascoot.bg). The novelty and thrill of gliding through streets appeal to tourists and locals alike. This “fun factor” has turned e-scooters into not just transport, but also a form of recreation. In Sofia, groups of friends rent scooters to cruise through Borisova Garden or along Vitosha Boulevard on weekends. The combination of practicality and enjoyment has firmly embedded e-scooters into the urban lifestyle for many Bulgarians.

Recent Issues: Injuries, Nuisance, and Social Costs

As e-scooters proliferated, safety incidents and public nuisance problems have also risen. The convenience of trottinettes has been accompanied by a surge in accidents – some minor, but many quite serious. Bulgarian emergency rooms have reported a notable increase in injuries related to electric scooters over the past few years. According to data from the National Police, since the beginning of 2024, there were 323 traffic accidents involving e-scooter riders, resulting in 5 deaths and 192 injuries (in just the first seven months of the year) (novinite.com). These sobering figures highlight that e-scooters are not harmless toys; accidents can and do happen, sometimes with fatal consequences. For context, those incidents from January through July 2024 equate to nearly 46 scooter accidents per month on average, a significant public safety concern.

Most commonly, e-scooter riders suffer injuries from falls or collisions, ranging from cuts and bruises to broken bones and head trauma. Medical professionals have grown alarmed at the pattern of head injuries in particular. One European study found helmet usage was only about 4% among e-scooter riders involved in crashes, leading to a high proportion of head trauma among victims (euronews.com). Bulgaria reflects this trend: despite a legal helmet mandate for minors, the vast majority of adult riders go helmetless, increasing their risk. A neurosurgeon at Burgas University Hospital noted that many of the e-scooter patients he treated not only lacked helmets but had been riding “after use of alcohol” as well (trud.bg). Indeed, riding under the influence has become an issue, especially late at night – a number of scooter crashes occur when riders have been drinking, akin to DUI incidents with cars, though enforcement is challenging.

Pedestrians have also been victims in some cases. There have been reports (including CCTV footage circulated in the media) of pedestrians being knocked over by reckless scooter riders. While many such encounters result in scares or minor injuries, some have been severe. For example, officials recounted incidents of scooters colliding with pedestrians and cars, and even a case of a scooter battery spontaneously igniting (“self-ignition”) while charging, causing a fire hazard (novinite.com). The diversity of accidents – from technical malfunctions to high-speed collisions – underscores the multifaceted safety challenge.

Beyond accidents, public nuisance complaints have accompanied the scooter boom. Residents in Sofia and other cities have grown frustrated with scooters being improperly parked or discarded in random places. “Continuous complaints about improperly parked electric scooters” were noted by the Sofia city council (novinite.com). Early on, users would often end rides wherever convenient – on sidewalks, in front of doorways, even blocking wheelchair ramps. It became common to see e-scooters littering park lawns or strewn across pavements, obstructing pedestrians. In a two-year span, the Interior Ministry recorded 1,604 violations by e-scooter users, many likely related to such misbehavior. Social media in Bulgaria is filled with photos of fallen scooters cluttering public spaces, fueling a perception of trottinettes as an “urban blight” when not orderly managed.

Another nuisance issue is scooters being ridden on sidewalks or in pedestrian zones. Although illegal (as will be discussed in the regulations section), enforcement initially lagged, and many riders – especially teenagers – took to zipping through crowds on sidewalks, startling walkers. This led to understandable anger from pedestrians who felt their safety and comfort were being compromised. In central Sofia’s pedestrian promenades (like Vitosha Blvd.), it became enough of a problem that the municipality proposed explicit new rules to curb sidewalk riding. The sight of two people riding tandem on a single scooter (also illegal) or youths racing at top speed in pedestrian areas gave e-scooters a bad image in the eyes of many Bulgarians who weren’t using them.

The social costs of the e-scooter trend are also coming into focus. City authorities have had to devote resources to deal with scooter-related issues, from policing and issuing fines to physically removing obstructive scooters. Sofia’s municipal government found it necessary to impose obligations on the rental companies to remove any scooter “abandoned” on the streets within 4 hours (or 6 hours on weekends) or face fines. In essence, what started as free-market innovation required governance to prevent urban chaos. There are also economic costs to consider: accidents incur medical expenses (often borne by the public healthcare system if the rider lacks private insurance), and injured persons may lose work days. To date, Bulgaria has not implemented a dedicated insurance requirement for e-scooter users, meaning a pedestrian hit by a negligent rider could face difficulties obtaining compensation, a social cost in terms of justice, and healthcare.

Finally, the environmental benefits of scooters – one of their selling points – can be partially offset by real-world practices. Shared e-scooters need regular collection for charging or rebalancing, typically using gasoline-powered vans. In the early days, scooter units also had short lifespans (sometimes just a few months) due to vandalism or wear and tear, leading to e-waste and resource use. Studies in other countries have shown that if a scooter ride substitutes walking or cycling (rather than a car trip), it actually adds emissions (from the operational logistics) rather than reducing them. That said, as mentioned earlier, operators in Bulgaria are adopting best practices (longer-life scooters, swappable batteries, greener operations) to improve the net environmental outcome. So while e-scooters can contribute to lower emissions and cleaner air, these gains depend on responsible usage and management – a lesson Bulgarian cities are actively learning and addressing.

Key Facts and Statistics in Bulgaria’s E-Scooter Boom

To grasp the scope of the trottinette phenomenon in Bulgaria, it’s useful to highlight some key facts and figures:

Explosion in Usage

From a virtually zero presence in 2018, Bulgaria’s e-scooter user base grew to tens of thousands by 2023. Sofia alone counts over 10,000 e-scooters in use (private and shared combined). Three major operators (Lime, Bird, and Hobo – now joined by others like Bolt and BinBin) deployed roughly 2,000 scooters for rent in the capital, and they report thousands of rides per day during peak season. While exact ride numbers are proprietary, Lime’s global trends indicate heavy usage; in one city (Washington D.C.), Lime saw nearly 5.9 million scooter rides in 2024. Sofia’s scale is smaller, but local operators have undoubtedly logged hundreds of thousands of rides annually as the trend matured.

Accident Rates

Traffic data confirms a rising accident count. In 2022, police reported hundreds of e-scooter-related accidents nationwide (the precise number wasn’t officially published, but 2024’s mid-year 323 accidents suggest annual totals well into the hundreds). Notably, 5 fatalities occurred in the first seven months of 2024 alone. For comparison, France (with a far larger ridership) recorded 27 e-scooter deaths in all of 2021. Bulgaria’s per-capita fatality rate from e-scooters appears high, reflecting both usage growth and safety gaps. Injury patterns show head and limb injuries as most common – Bulgarian hospitals echo global observations that head trauma is frequent when riders don’t wear helmets (euronews.com).

User Demographics

E-scooters are predominantly used by young people in their teens, 20s, and 30s, though not exclusively. In Sofia, rental companies require users to be 18+ (by terms of service), but it’s known that some under-18 teens still use shared accounts. The legal minimum age to ride is 14 (with restrictions) – effectively, high school and university students form a large segment of riders. That said, many working professionals in their 30s and 40s have adopted scooters for short commutes. It’s not uncommon to see someone in office attire scooting to a meeting. An interesting niche: tourists and expats. Sofia’s travel guides encourage visitors to try e-scooters as a novel way to sightsee; the In Your Pocket guide noted e-scooters have become “really popular among all ages all over the world” and highlighted Lime’s launch as a new tourist-friendly option (inyourpocket.com). This has added an international flavor to the user mix, with foreign students and tourists often spotted on rental scooters in city centers.

Public Opinion

Bulgarian public opinion on e-scooters is mixed and evolving. There is a clear appreciation among users for the convenience and fun factor. However, non-users (especially motorists and pedestrians) have voiced concerns. Anecdotally, online forums reflect a divide: some hail scooters as a cool, eco-friendly mode of transport, while others label them a menace. The nuisance issues (clutter, sidewalk riding) initially gave e-scooters a somewhat negative image in local media by 2020. However, as regulations catch up and companies cooperate in maintaining order, public sentiment may be improving. Notably, Sofia did not experience a severe backlash to the extent of banning scooters (unlike Paris, where 2023’s referendum led to a ban on rentals). A possible indicator of acceptance is that Bulgarian authorities are focusing on tighter management rather than the elimination of e-scooters. As Deputy Mayor of Sofia, Ilian Pavlov stated, “scooters are an important part of alternative urban mobility, on par with bicycles”, and the goal should be to encourage their use while regulating speed and parking to protect pedestrians (dnes.bg). This pragmatic approach suggests that, despite problems, e-scooters are seen as a net positive if properly managed.

Company Data and Response

The micromobility companies themselves have provided some statistics and commitments. Hobo’s founders indicated their scooters were being used intensively in Sofia, enough that they pursued expansion and partnerships after the pilot. Lime globally reported that by 2021, its riders had taken over 200 million trips in dozens of cities, reducing an estimated 50+ million car trips. Bulgarian cities contribute modestly to those figures but are part of that narrative. Facing safety concerns, companies have begun sharing incident data; for example, a mobility industry alliance reported an injury rate of about 5.1 injuries per million kilometers ridden on shared e-scooters in 2021 (li.me). While Bulgaria-specific rates aren’t published, operators like Lime and Bolt have an incentive to demonstrate safety improvements (through better scooter hardware, in-app education, etc.). They often coordinate with city officials on measures like geofencing slow zones and hosting safety events (helmet giveaways, training sessions), though more could be done in Bulgaria.

The numbers tell a story of rapid adoption outpacing safety precautions. Thousands of Bulgarians are riding e-scooters, millions of kilometers are being traveled, and inevitably, incidents have increased. The challenge now is to bend those negative statistics downward through effective regulation and responsible use, without losing the positive mobility benefits the statistics also hint at (e.g., reduced car trips). The next sections examine how Bulgaria is regulating this sector and how those efforts compare with other countries’ experiences.

Companies Operating in Bulgaria: Local and International Players

The Bulgarian e-scooter market features a mix of international giants and homegrown startups. Here are the key companies that have been operating services:

- Lime – The San Francisco-based pioneer of scooter sharing. Lime entered Sofia in 2019 with much fanfare, deploying an initial fleet of 100+ scooters. Lime’s bright green scooters (model Gen3/Gen4) became a familiar sight in Sofia’s center and business districts. Lime brought experience from other European cities and set the standard for operations (daily charging, in-app maps, etc.). It generally maintains the 25 km/h speed cap and relies on a local team or contractors to collect/charge scooters nightly. Lime did not immediately expand beyond Sofia, but their presence in the capital established the concept and spurred competition.

- Bird – Another major California-based operator, Bird, also launched in Sofia in late 2019. Bird partnered with a local Bulgarian company called BRUM for on-ground logistics. Bird’s scooters and pricing were similar to Lime’s (they even initially matched Lime’s unlock and per-minute fees). For a time, Bird and Lime were head-to-head in Sofia’s most frequented areas, giving consumers a choice. However, by 2021-2022, Bird reportedly scaled back in some smaller markets worldwide, and anecdotal evidence suggests Bird’s fleet in Sofia might have reduced or been absorbed by other brands. (A Reddit user in 2022 noted that in Sofia, “only BinBin and Lime” were commonly seen, calling Lime scooters “trash” and preferring BinBin (reddit.com) – implying Bird had lost prominence). Nonetheless, Bird’s entry was crucial in validating the Bulgarian market for micromobility.

- Hobo – Bulgaria’s first indigenous e-scooter sharing company. Launched in September 2019, Hobo was founded by Teodor Rachev and Todor Todorov, who trialed scooters abroad and decided to build a local service. They invested in a fleet of robust Acton scooters (with inflatable tires suitable for Sofia’s bumpy roads) and actively liaised with Sofia Municipality on regulatory frameworks. Hobo distinguished itself with local know-how – e.g., they planned 120 designated parking zones downtown to impose order from the start. Hobo’s pricing undercut big players (BGN 0.10 per minute vs Lime’s BGN 0.15 at the time), and they even introduced monthly passes for frequent users. As a startup, Hobo had a smaller fleet, but it resonated with users who wanted to support a Bulgarian brand. The company gained media attention as a “Bulgarian e-scooter service” making waves (trendingtopics.eu). Hobo continued operating through the early 2020s, though competition is stiff; its current status is somewhat low-profile, possibly focusing on specific niches or corporate clients.

- Shareascoot – A Bulgarian platform with a twist: instead of stand-up kick scooters, Shareascoot offers electric mopeds (scooter motorcycles) on a sharing basis. Their service in Sofia provides seated scooters (with a top speed around 50 km/h) that come with a helmet in the trunk and require a valid driver’s license to operate. Shareascoot positions itself as a way to “discover Sofia and the surroundings on a scooter” (shareascoot.bg) – effectively a bridge between lightweight e-scooters and traditional motorcycle rentals. The rules for users are stricter: you must be at least 18 and licensed, and helmets are provided and must be worn. Shareascoot’s pricing (noted earlier: 5.90 BGN for 10 min, etc.) targets longer rides, and the service includes insurance and maintenance handled by the company. While serving a slightly different market segment, Shareascoot is part of the broader micromobility ecosystem and is often mentioned alongside stand-up scooter services as a local player.

- BinBin – A newcomer in the Bulgarian scene, BinBin is a micromobility operator originally from Turkey. By 2023, BinBin’s teal-colored scooters appeared in Sofia, reportedly providing a quality alternative to Lime. Users commented that “BinBin is good” and more reliable than older Lime units (reddit.com). BinBin likely entered via winning a portion of municipal permission or simply as a private rollout. BinBin’s expansion to Sofia is part of a trend of regional players (from Turkey, the Balkans) moving into Eastern European markets. They typically offer comparable pricing and adhere to local rules, possibly with slight app differences. BinBin’s presence increases competition, which can improve service for users (e.g,. better scooter quality or promotions).

- Bolt – Originally known for ride-hailing (the “European Uber”), Estonia-based Bolt has aggressively expanded into micromobility across Europe. In Bulgaria, Bolt first offered e-scooter rentals in the seaside city of Burgas and later Varna (popular tourist spots). In 2023, Bolt launched in Plovdiv with a large fleet and is now in Sofia as well. Bolt leverages its existing user base from the ride-hailing app; anyone with the Bolt app can also rent scooters, providing seamless integration. Bolt’s scooters are custom-designed (by 2025 they introduced a sixth-generation scooter model with improved safety and an 8-year lifespan, forbes.com). Bolt typically prices rides slightly lower than Lime and emphasizes safety features (like dual brakes, sturdy build). Their entry into more Bulgarian cities (including medium-sized ones) could significantly shape the market, as they have the capital and experience to scale up. Bolt is also known to work closely with local authorities – for example, adhering to any geofenced slow zones and sharing data when required.

- Other Operators: Over the years, a few other names have popped up. Tier (a German micromobility firm) was rumored in 2019 as a potential entrant in Sofia, but it appears they did not launch at that time (Tier instead focused on Western Europe and later acquired Voi, another operator). Voi did not operate in Bulgaria. Some local rental shops in resorts rent out electric kick scooters on an hourly basis (targeting tourists, outside of app-based systems). In addition, app-based bike-sharing services like Cyrcl (which launched in Sofia with bicycles) (therecursive.com) have eyed adding e-scooters to their fleet, though their core remains pedal bikes.

The presence of multiple companies has forced operators to differentiate and uphold service quality. Importantly, all the rental operators must comply with Bulgarian laws and any city regulations. They have generally done so by: capping scooter speeds to 25 km/h via software, not allowing rides on forbidden roads in the app’s map, and communicating age/helmet rules to users (e.g., requiring age verification by ID or driver’s license scan upon signup in some apps). The companies also carry their own insurance for liability, at least for the shared fleets (covering damages to third parties, etc., although users are often financially responsible for any misuse or damage under the rental agreement).

This competitive landscape has ensured that Bulgarians have options when it comes to e-scooters, and it’s not just a monopoly by one big tech firm. Local startups like Hobo and Shareascoot proved that Bulgarian entrepreneurs can innovate in this space, while the globals like Lime and Bolt bring operational expertise. The mix ideally pushes everyone toward safer, more efficient operations, since a bad accident or city ban would hurt all players. Thus, we see companies in Bulgaria increasingly participating in safety initiatives, sharing data with authorities, and tweaking their deployments (e.g., designated virtual parking zones in apps) to address public concerns.

Current E-Scooter Regulations in Bulgaria

When e-scooters first hit Bulgarian streets, there was a regulatory void – no specific laws existed for these devices. Riders took to sidewalks and roads with impunity, which soon raised alarms. The government recognized the need to legislate this new form of transport. After some deliberation and drafts, Bulgaria introduced a set of rules for electric scooters in July 2020, by amending the Road Traffic Act. These rules, in effect since 07.07.2020, provide a legal framework governing who can ride e-scooters, where, and how. Below is an overview of the current Bulgarian regulation of e-scooters, including speed limits, age restrictions, safety requirements, and enforcement measures:

- Maximum Speed: 25 km/h. Electric scooters (as “individual electric vehicles”) are legally capped at 25 kilometers per hour on public ways (bntnews.bg). Riders are not allowed to go faster than this. Most shared scooters are programmed not to exceed this speed. The law notes that many scooters don’t have visible speedometers, so users must find ways to gauge their speed or err on the side of caution. Exceeding 25 km/h is an offense punishable by a fine (50 BGN). Essentially, e-scooters are treated similarly to bicycles in terms of speed and range.

- Minimum Age: 14 years. Bulgarian law sets graduated age rules:

- Under 14: No one under 14 may operate an e-scooter on public roads. It’s outright forbidden (and parents could be liable if a child violates this).

- 14–15 years old: Can ride a scooter only on dedicated bicycle infrastructure (bike lanes or paths). They are NOT allowed to ride on streets alongside cars. So, a 14 or 15-year-old can use a scooter in a park bike lane or a city bike lane, but cannot go out into regular traffic lanes.

- 16–17 years old: Allowed to ride on roads, but only those roads where the speed limit is up to 50 km/h (bntnews.bg). This basically allows older teens to use e-scooters on most city streets (which typically have 50 km/h limits or lower), but bars them from high-speed roads. The logic is that by 16, they have some road sense (16 is also the age at which one can get a moped license or learner driver’s permit in many places).

- 18 and above: Adults have full rights to use e-scooters wherever it’s otherwise legal (again, roads ≤50 km/h or bike lanes), with no additional age-based restrictions.

These age rules aimed to keep the youngest riders (who may be less cautious or skilled) in safer environments like bike lanes. If a person under 16 is caught riding on a normal road or a person under 14 riding at all, a fine of 50 BGN can apply. In practice, enforcement of age relies on police stopping a rider and checking ID if they look underage.

- Protective Gear – Helmet and Reflectors: Helmet use is mandatory for riders under 18 years old. This means minors (14–17) must wear a helmet when operating an e-scooter. Failure to do so can result in a 10 BGN fine. For adults 18+, helmet use is not legally required (a point of contention among safety experts). The law’s omission of an adult helmet mandate was criticized as a “serious shortcoming” by some, who argue that adults are just as vulnerable in crashes. Indeed, efforts are underway to change this: in mid-2024, proposals were introduced to make helmets compulsory for all e-scooter and bicycle riders regardless of age, and to increase the fine for non-compliance to 100 BGN. As of May 2025, however, that broader helmet rule is not yet in force – it remains a proposal pending adoption. In addition to helmets, the law requires reflective clothing or elements at night for all riders. After dark or in low visibility, one must wear something like a reflective vest or strips so that the person is easily visible. Not wearing reflective gear at night carries a 10 BGN fine. Also, the e-scooter must have its lights turned on at night (front and rear lights are obligatory equipment), and riding without lights in the dark can incur a 50 BGN fine.

- Where You Can Ride: The law is quite specific about permitted and forbidden areas for e-scooters:

- Bike Lanes/Paths – E-scooters are explicitly allowed on bicycle infrastructure and in fact must use it where it exists. If there’s a bike lane available on a road, a scooter should ride in that lane, not the main car lanes. This aligns with treating e-scooters similarly to bikes.

- Roadways (Car Lanes) – Scooters may ride on regular roads only if the road’s speed limit is 50 km/h or less. They must ride as far to the right side as practicable when in a car lane, to let faster vehicles overtake safely. They cannot ride on highways or high-speed boulevards where cars go faster than 50 kilometers per hour. The only exception is if a faster road has a separate bike lane – then scooters can ride in that protected lane even if the adjacent road’s limit is over 50. In practice, this means e-scooters stick to city streets, residential areas, and some rural roads, but not inter-city highways.

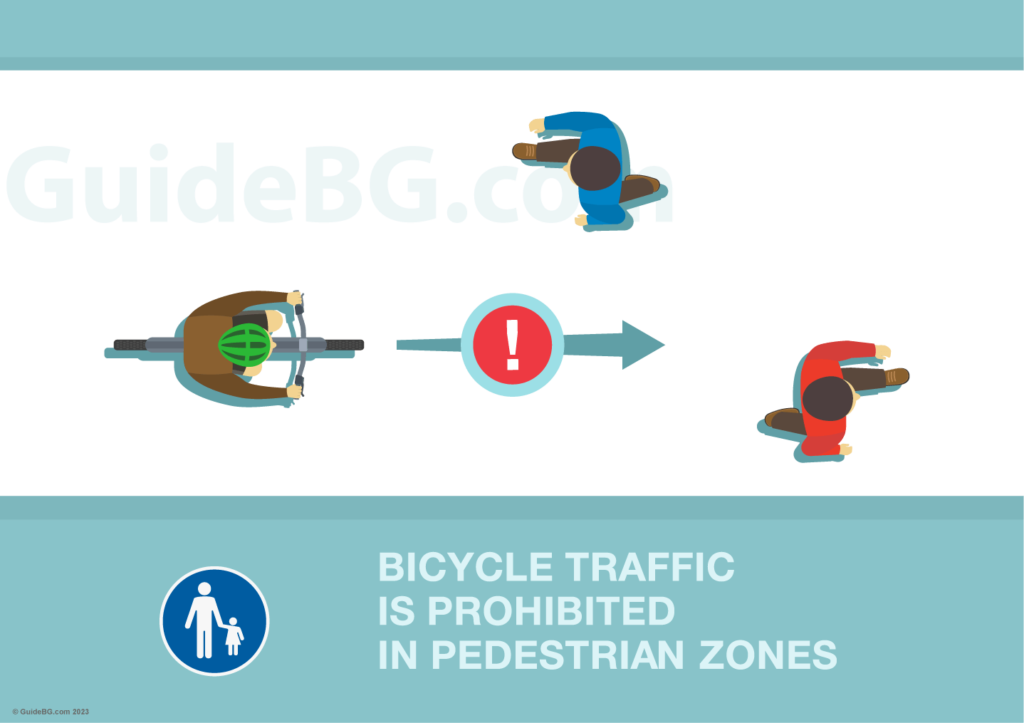

- Sidewalks – Riding on sidewalks is strictly prohibited. Just like cyclists, scooter riders in Bulgaria are not allowed to zip through pedestrian sidewalks. If a rider needs to use a sidewalk or cross a pedestrian zone, they must dismount and push the scooter (essentially behaving as a pedestrian). Violating this (riding on the pavement) can lead to a 50 BGN fine. (The only nuance: local councils can allow riding in certain pedestrian areas at walking speed, but Sofia and others have generally banned it, as we’ll see in Sofia’s rules).

- Pedestrian Zones/Parks – By national law, any area marked with a sign forbidding bicycles is also off-limits to e-scooters. This would include certain pedestrian plazas, promenades, or park trails where cycling is not allowed. Many parks do allow cycling on designated paths, which then would allow scooters too (again at 25 km/h max, or slower if posted). Notably, Sofia Municipality has additionally banned scooter riding in specific central pedestrian zones and parks via city ordinance, which we will detail separately – but the general rule is if an area is meant purely for pedestrians (no bikes), scooters can’t be ridden there either.

- Bus Lanes – E-scooters cannot ride in dedicated public transport lanes (bus/tram lanes). Those lanes are reserved for mass transit and sometimes taxis, and scooters are specifically forbidden to mix there (to avoid impeding buses).

- Roadway Conduct – On roads, scooters must keep as far right as possible and generally behave like a cyclist. They are not allowed to ride two abreast alongside another scooter or bike in the same lane (no parallel riding) – they should go single-file. They also must not cling to another vehicle (no grabbing a car to be towed, obviously).

- Rider Behavior Rules: Several common-sense rules are codified:

- One Person per Scooter – It is illegal to carry a passenger on an e-scooter. The design is for one person, and riding tandem makes it unstable. Yet occasionally, you’d see two teens on one scooter; this is punishable by a 50 BGN fine for the rider.

- Hands on Handlebars – Riders must keep at least one hand on the handlebars at all times. “No-hands” riding or stunts are forbidden (fineable offense).

- No Mobile Phone Use – Using a mobile phone (texting, calling) while operating the scooter is banned. This is akin to distracted driving laws for cars. If caught using a phone while riding, that falls under the 50 BGN fine category as well (for breaking traffic rules). Essentially, riders should stop if they need to check their phone or GPS.

- No Towing/Hauling – Scooters can’t be used to pull or push another object, and you shouldn’t drag a big item while ridingThis is to ensure stability and safety of others.

- Alcohol/Drugs – Scooter riders, like any vehicle operator, are subject to DUI laws. It is forbidden to ride with a blood alcohol concentration over 0.5‰ (0.5 BAC) or under the influence of narcotics. However, unlike driving a car, getting caught drunk on a scooter does not carry criminal penalties (unless extremely high BAC); it’s treated with an administrative fine of 20 BGN for 0.5–1.2‰ (over 1.2‰ might involve more serious charges under general road law). The fine is surprisingly low (20 lev is about €10), perhaps because lawmakers saw e-scooters as less dangerous than cars, though drunk scootering can certainly injure the rider (and others). Police have the power to stop riders and conduct breathalyzer tests, though doing so in practice may be rare unless an accident occurs.

- Vehicle Requirements: By law, an e-scooter must have certain equipment:

- Brakes – A functional braking system is required on e-scooters. It should be capable of stopping the scooter effectively. Riding a scooter with faulty brakes is illegal (fine 50 BGN).

- Lights and Reflectors – Scooters must be equipped with front white light and rear red light, plus reflectors. At night these lights must be on. This ensures visibility. The police emphasize technical soundness: “functional brake systems, proper lights, and an electronic or mechanical bell” are the first requirements for these vehicles to be street-legal. A bell or horn is also required for audible signaling.

- No Registration for “Personal Light Electric Vehicles” – Importantly, the small e-scooters (up to 25 km/h, without seat) do not require registration or license plates. They are explicitly not considered motor vehicles that need to be registered with the traffic police (KAT), and no driver’s license is needed to operate them. They are treated similarly to bicycles under the law. However, if a scooter does not meet the criteria of an “individual electric vehicle” (for example, it’s more powerful or has a seat), then it falls into another category. The law provides that vehicles that exceed the limits will be evaluated case-by-case to see if they qualify as a moped or motorcycle that does not need registration. The Road Traffic Act defines that electric scooters with motor power between 250W and 4,000W, capable of speeds >25 km/h up to 45 km/h, and equipped with a seat (above a certain height) are classified as L1e mopeds, requiring registration and at least an M category license (or B category car license, which covers M). In short, the typical stand-up e-scooters (often ~300W motors but limited to 25 km/h, usually no seat) are unregistered personal vehicles. But if you buy a high-powered scooter or one with a seat (like an electric mini-motorcycle), you likely must register it, insure it, and wear a full motorcycle helmet, etc. This is relevant to Shareascoot’s mopeds and some private owners who import powerful e-scooters – they must adhere to the moped rules (including technical inspection every 2 years as mandated since Jan 2023 for registered e-scooters, motorettagroup.com).

- Penalties and Fines: The law outlines specific fines for infractions, as already noted:

- 10 BGN (~€5) for minors not wearing helmets or anyone without reflective clothing at night.

- 50 BGN (~€25) for a wide range of violations: exceeding 25 km/h, no lights at night, riding in prohibited areas (sidewalks, highways, bus lanes), riding in parallel or with a passenger, underage on the road, etc..

- 20 BGN (~€10) for riding under the influence of alcohol or drugs (if not at criminal level).

- These fines may seem low relative to other countries (e.g., France fines €135 for sidewalk riding, evz.de), but Bulgaria’s fines for traffic offenses in general are lower in absolute terms due to economic differences. Nevertheless, proposals exist to raise some of these (like the helmet fine to 100 BGN as mentioned).

Municipalities have the authority to impose stricter rules in addition to national law. The Road Traffic Act explicitly empowered city councils to introduce more stringent regulations tailored to local conditions. Sofia took advantage of this, as discussed in the next section. Other cities can regulate things like lower speed limits in certain zones, special parking requirements, or additional age limits, as long as they don’t contradict national law.

Bulgaria’s e-scooter regulations as of 2025 provide a comprehensive base: they treat e-scooters similarly to bicycles with extra provisions for motor power and youth safety. The law came about a year and a half after their first appearance on Bulgarian roads, but since mid-2020, there has been a clear legal framework. The emphasis now is on enforcement and refinement. Police have been urged to enforce these rules strictly. Reality, however, shows many riders still break rules (e.g., going on sidewalks, minors without helmets), so enforcement needs to catch up. Bulgarian authorities are actively working on amendments (like helmet requirements for adults, higher fines) to address observed shortcomings. As we will see, cities like Sofia are adding their own layer of regulations to tackle issues like high-risk zones and parking chaos.

What Bulgarian Regulations Lack (Compared to Other Countries)

Although Bulgaria has implemented a solid foundation of e-scooter laws, there are several areas where its regulatory approach lags behind other EU countries and global best practices. By examining measures in places like France, Germany, Denmark, Singapore, etc., we can identify which regulatory tools Bulgaria has not yet adopted or fully enforced. Here are the key regulatory gaps and differences:

Mandatory Insurance for Riders

Unlike some Western European countries, Bulgaria does not require any form of insurance for e-scooter users (for the standard 25 km/h scooters), (evz.de).In France, by contrast, anyone operating an e-scooter must have third-party liability insurance – riding uninsured is illegal (euronews.com). Germany similarly mandates that e-scooters carry an insurance sticker (indicator of liability insurance) as a prerequisite for use on public roads. Denmark and (for trials) the UK also impose insurance requirements. Bulgaria has no such requirement for the small e-scooters; only if a scooter is classified as a moped (registered) would normal vehicle insurance rules kick in. This gap means that if an e-scooter rider causes injury or property damage to someone else, there is no automatic insurance coverage – the victim might have to pursue the rider personally. Many countries view this as unacceptable, hence mandating insurance to protect third parties. Bulgaria could face pressure to reconsider this, especially since an EU Motor Insurance Directive (Jan 2024) includes e-scooters unless exempted by national law. As of now, Bulgaria has chosen to exempt the “lighter/slower” scooters from registration and insurance, but this is an area where it lags behind best practice for liability coverage.

No License or Training Requirement

In Bulgaria, no driving license is needed to use an ordinary e-scooter. This is common in many countries (treating them like bicycles), but some jurisdictions have introduced at least an informal training or permit for scooter users. For example, Singapore requires e-scooter riders to pass an online theory test before they can ride on public paths (onemotoring.lta.gov.sg / lta.gov.sg), ensuring they know the rules. The UK, during its ongoing rental trials, limits rentals to those with a valid driver’s license (provisional or full) as an age/skill proxy. Germany and France do not require a license, and neither does Bulgaria, but the downside is no guaranteed knowledge of traffic rules. A 14-year-old Bulgarian can legally ride a scooter on a bike lane with zero formal training. By contrast, to ride a moped at 14 requires at least a basic AM license in many countries. Bulgaria’s approach differs by treating e-scooters more leniently than even mopeds. Some experts suggest that at a minimum, public education campaigns are needed to fill this gap. Indeed, Bulgarian road safety advocates have called for widespread awareness campaigns so that riders voluntarily learn the rules and safe behavior, noting that simply raising fines won’t ensure compliance. Compared to, say, Denmark, which often accompanies new bike/scooter rules with education, Bulgaria has room to improve on training and rider education.

Lower Fines and Lenient Penalties

Bulgaria’s fines (10–50 BGN for most offenses) are quite low by EU standards. In many EU countries, e-scooter violations incur fines of €50–€150 (100–300 BGN) or more. For instance, riding on the sidewalk in Belgium can cost €55; in France, it’s €135. Germany issues €40 for no insurance, €70 for no operating permit, and up to €100-200 for various traffic violations. Bulgaria’s 50 BGN (~€25) fine for moving violations or misparking may not be a strong deterrent, especially for younger riders who may gamble on not getting caught. Similarly, the token 20 BGN fine for drunk riding is extremely lenient – in many countries, drunk e-scooter riding is treated like drunk driving, with fines in the hundreds or even loss of driving privileges (Germany will prosecute e-scooter DUIs under motor vehicle laws, leading to license suspension in serious cases). Bulgaria’s current approach to DUI on a scooter is arguably too lax, given the potential harm. The lack of license linkage (you don’t need a license, so there’s no license to suspend if you offend) also means habitual bad actors face limited consequences beyond small fines. This is an area of difference: other industries like car driving or even cycling in some places have stiffer penalties (e.g., cyclists in the Netherlands can get hefty fines for infractions despite no license requirement). Bulgaria may need to raise e-scooter fines or introduce escalations for repeat offenders to match the seriousness seen elsewhere.

Helmet Rule for Adults

As noted, Bulgaria currently only mandates helmets up to age 18. Many European countries likewise do not force adults to wear helmets on e-scooters – France, Germany, etc., leave it optional (though recommended). However, a few are moving toward stricter rules. Spain in 2021 introduced a national requirement for e-scooter riders to wear helmets (though enforcement has been uneven, and some cities had their own rules). Italy’s government has debated making helmets compulsory for all ages (currently, Italy requires them only for those under 18). The Euronews analysis in 2023 found that in 16 of 21 surveyed countries, helmets are not obligatory for adults (euronews.com) – so Bulgaria is actually in line with the majority here. Still, given the high injury rates and expert recommendations, Bulgaria is considering leading on this front by making helmets universal. If it does, it would join a small group of countries (Austria, Czechia, and Sweden require it for minors; very few require it for all). Another nuance: helmet quality and usage. Even where not mandated, some countries at least emphasize it strongly (e.g., public rental schemes in the US sometimes attach reminder messages or even provide helmets in some markets). In Bulgaria, neither Lime nor other operators provide helmets to users of standing scooters, and adoption among adults is extremely low. So the gap is not just legal but cultural – a helmet campaign could help, as Bulgaria has successfully done for car seatbelts in the past.

Speed Limit Enforcement & Lower Local Limits

While Bulgaria has the 25 km/h cap nationally, some countries enforce lower limits in certain areas or overall. For example, Germany’s max is 20 km/h by design for e-scooters (evz.de). Sweden recently lowered the allowed e-scooter speed to 20 km/h as well. Many cities (Paris, Brussels, etc.) imposed even lower speed zones: Paris had 20 km/h citywide for scooters and 10 km/h in designated slow zones (before the ban) and Brussels limits rentals to 8 km/h in pedestrian areas. Sofia’s new rules similarly call for 5 km/h limit in specific pedestrian-heavy zones (essentially walking speed, basically requiring you to push). However, Bulgaria at the national level doesn’t have a concept of geofenced slow zones – it leaves it to municipalities. Until Sofia’s ordinance, there wasn’t systematic enforcement of, say, 5 km/h in parks. Estonia and Hungary apparently had no specific scooter speed limits as of 2023, but those are outliers. So Bulgaria might “lack” only in enforcement: do scooters actually respect 25 km/h? Shared ones usually yes (software-limited), but private ones could be modified to go faster without much fear of detection (no speed cameras checking a scooter’s speed typically). In countries like Germany, police have occasionally impounded illegally modified scooters that exceed 20 km/h or lack approval. In Bulgaria, such enforcement has been minimal so far.

Parking Regulations and Infrastructure

Many cities abroad have introduced strict rules about scooter parking to prevent sidewalk clutter. This includes requiring scooters to be parked in designated racks or painted boxes on the sidewalk, or at least upright out of pedestrian flow, and imposing fines or even impounding scooters that are left improperly. Paris banned any scooter from being left outside of designated spots (before the ban altogether). German cities like Munich and Frankfurt have bylaws to fine companies for scooters blocking sidewalks. Bulgaria’s national law did not originally specify parking rules for e-scooters beyond the general requirement not to obstruct traffic (which is a broad rule for any object on a public way). This was a gap addressed by local authorities: Sofia’s 2023 ordinance explicitly prohibits parking e-scooters on sidewalks, in parks, near building entrances, etc., except in marked spots. It also compels companies to show permitted parking zones in-app and remove misparked units quickly (novinite.com). Prior to these local rules, parking was a free-for-all and clearly a weak point in regulation. Other Bulgarian cities lag Sofia in this regard – as of 2025, Plovdiv, Varna, etc., haven’t publicly rolled out detailed scooter parking rules (likely watching Sofia’s example). So until recently, Bulgaria lacked dedicated infrastructure like scooter docks or mandated parking zones, which other countries have implemented. The situation is improving at least in the capital.

Limiting Fleet Numbers and Managing Public Space

Many major cities control the number of scooters and operators via permitting systems – e.g., Paris (before banning) limited to 3 operators, 5,000 scooters each; Stockholm similarly limits fleet size and issues a fixed number of licenses. This prevents oversupply and ensures accountability. In Bulgaria, so far, no city has formally capped the number of e-scooters or run a tender for operators. Sofia has three main operators organically; Plovdiv welcomed Bolt without limiting others; Varna/Burgas have a couple each. The market isn’t saturated to the extreme levels seen in some Western cities yet, but as it grows, the absence of an operator licensing scheme could become an issue. The EU’s “themotor.eu” and other such municipal networks encourage cities to set terms for operations (including fees, data sharing, equity requirements for distribution). Bulgarian cities might be behind in establishing those frameworks. For instance, data sharing: Many cities abroad require companies to share anonymized trip data with city planners to help with infrastructure decisions. Sofia has not announced such a requirement publicly (though collaboration may exist). This kind of integration of scooters into urban mobility planning is still nascent in Bulgaria.

Infrastructure Development

While not a “regulation” per se, one could argue that Bulgaria lags in dedicated infrastructure for micro-mobility compared to countries like the Netherlands or Denmark. The law can say “ride in bike lanes,” but if bike lanes are scarce or poorly designed, safety suffers. Sofia has been expanding its bike lane network gradually, but it’s still far from comprehensive. Other cities have very few bike lanes. By contrast, the Netherlands essentially solved many e-scooter issues by virtue of ubiquitous cycling infrastructure (though the Netherlands actually bans most e-scooters unless type-approved as mopeds). In Bulgaria, riders often have no choice but to mix with cars or pedestrians due to a lack of lanes, which the regulation doesn’t fix. So one could say Bulgaria lacks the effective integration of scooters via infrastructure. The Sofia Deputy Mayor acknowledged that “all built bike lanes are also for scooters” and that more are needed (dnes.bg). Until those lanes exist, the best regulations might still fall short of ensuring safety. Other countries also experiment with innovative infrastructure (like scooter parking docks on streets, charging stations, etc.), which are not yet present in Bulgaria.

Bulgaria’s regulatory approach, while solid in basic traffic rules, differs from more mature models in that it has lighter penalties, no insurance or licensing requirements, and relies on later local fixes for parking and operational oversight. It lagged about 1–2 years behind Western Europe in enacting rules (2019 vs 2020), and even now, some refinements (helmet for adults, etc.) are still playing catch-up. The country can learn from places that have imposed stricter controls or comprehensive strategies to reduce the negative externalities of e-scooters. As e-scooter use continues, it’s likely Bulgaria will tighten some of these gaps – indeed, proposals in Parliament and Sofia’s new ordinances indicate movement in that direction.

Economic and Socio-Economic Impact

Beyond safety and rules, the economics of e-scooters and their broader socio-economic impact in Bulgaria are important to analyze. Like any new mobility innovation, trottinettes come with costs and benefits not just to individual users but to communities and the economy at large. This section examines aspects such as affordability for users, environmental impact claims, costs from accidents, municipal expenses, and even benefits like job creation or tourism.

Affordability and Accessibility

One reason e-scooters took off is that they offered a relatively affordable mobility option, filling a gap between public transport and taxis/private cars. In Bulgaria, incomes are lower than in Western Europe, so cost matters greatly. The pricing schemes of shared scooters were discussed earlier (roughly 0.30 BGN/min on average, plus a small unlock fee). Let’s put that in perspective: A typical 2 km ride might take 6–8 minutes, costing around 3–4 BGN (~€1.5–€2). A single-ride ticket for public transport in Sofia is 1.60 BGN (about €0.80), so the scooter is a bit more expensive than a bus/tram for that distance, but much cheaper than a taxi (which would be ~5–6 BGN for 2 km). This means e-scooters are positioned as a semi-affordable convenience, not as cheap as subsidized transit, but within reach for many, especially for occasional use. Students and young people might not use them daily due to cost, but for those times one is running late or there’s no direct bus, a few leva for a quick scooter ride is justifiable.

The companies have also experimented with passes and discounts to improve affordability. Hobo’s idea of a monthly pass with included minutes (trendingtopics.eu), if implemented, would allow frequent users to budget a fixed amount for unlimited short rides. Lime at times offers bundles of free unlocks or minute packages at a slight discount. Shareascoot’s 24-hour rental for 59 BGN (shareascoot.bg) may attract users who need a scooter for a full day trip (divided among two people, even switching riders) – that’s about the price of a single day car rental for a small vehicle, which is notable. Competition among operators in Sofia has kept prices in check; for example, Lime initially was 1.50 + 0.30 (BGN), but later, one could find promotions or competing scooters slightly cheaper, preventing prices from rising. In some Western cities, prices went up over time once people were hooked, but in Bulgaria, the presence of Bolt (known for aggressive pricing) likely ensures they remain reasonably affordable.

One can also consider accessibility in terms of distribution: The shared scooters are concentrated in city centers and certain neighborhoods. This means they are most accessible to city dwellers and visitors in those areas. Outlying residential districts may see few if any scooters. In Sofia, for instance, wealthier and tourist areas (center, Lozenets, around Business Park) have them, whereas peripheral housing estates might not. This could create a bit of a mobility inequity if not addressed, similar to how bike-sharing often overlooks poorer neighborhoods. However, given the newness, Bulgarian cities have not yet tackled this via policy (some cities abroad require coverage areas in operator contracts).

For those who can afford to buy a personal e-scooter, the cost of ownership has also come down. A decent new electric scooter (like Xiaomi Mi or Ninebot) costs between 700 and 1500 BGN (€350-€750) in Bulgaria. That’s a one-time cost equivalent to a mid-range bicycle or a few months of public transport passes. Many young professionals opted to buy their own to avoid per-minute charges. As a result, not all scooters you see are rentals – plenty are privately owned, which, in the long term, is cheaper if one rides daily. The proliferation of private scooters indicates many Bulgarians find it an economical investment (especially those who don’t want to pay for parking or fuel for a car, or can’t afford a car).

Environmental Impact – Green Promise vs Reality

E-scooter companies heavily market the environmental benefits of micromobility. At face value, an electric scooter produces no exhaust and uses far less energy than a car, so replacing car trips with scooter trips should reduce emissions and pollution. Sofia’s smog and traffic congestion make this proposition very attractive – city officials explicitly cite scooters as part of efforts to improve air quality. If a commuter leaves their car at home twice a week and scoots instead, that’s a tangible drop in CO₂ and harmful particulates. Moreover, e-scooters are electric and can be charged from Bulgaria’s grid, which has a mix of sources, including renewables and low-emission nuclear, so their indirect emissions are moderate.

However, studies have shown that the life-cycle environmental impact of e-scooters is complex. Early analysis by the International Transport Forum (OECD) found that first-generation shared e-scooters had life-cycle emissions around 120 grams of CO₂ per passenger-km, surprisingly, similar to a fuel-efficient car (tier.app, and luskin.ucla.edu). The reason was the short lifespan (often <1 year) and the collection process (trucks driving around nightly). Since then, the industry has improved: newer scooters last longer (Lime’s latest are designed for ~5 years, Bolt claims 8 years for its new model, forbes.com), and many use swappable batteries (so vans no longer collect each scooter, workers swap batteries on-site and use cargo bikes or e-vans to do so). These improvements can dramatically cut the per-km emissions. A 2022 study showed shared e-scooters’ emissions fell by 30-50% compared to 2018 levels due to these changes (mdpi.com, and luskin.ucla.edu).

In Bulgaria, it’s likely that these greener practices are being adopted (Bolt and Lime certainly use the latest models; local Hobo might still need manual collection, but their scale is smaller). So the environmental claims are becoming more valid. If we consider “what if scooters didn’t exist,” would people walk or drive? Surveys globally have found that around one-third of scooter trips replace car trips, one-third replace walking, and the rest replace public transit or are new trips. If the same holds in Bulgaria, scooters probably do take some riders out of cars (good for emissions), but also some out of buses or off their feet (not as beneficial). The net effect is hard to measure exactly here, but it’s reasonable to say scooters have at least some positive environmental impact in Sofia – probably modest, but not zero. They also generate zero tailpipe emissions locally, which is great for city air (especially PM2.5 and NOx reduction, since they don’t burn fuel).

One environmental downside observed is waste and recycling: broken scooters and used batteries need proper recycling. In the early rush, some scooters were vandalized or tossed into rivers (Paris infamously had hundreds pulled from the Seine). In Sofia, there have been occasional acts of vandalism (a few scooters thrown in bushes or damaged), but not on a massive scale. Companies refurbish or recycle parts; Lime, for instance, has recycling programs. But Bulgaria will need to ensure these devices are disposed of responsibly at end-of-life. The mandatory technical inspection for registered powerful e-scooters introduced in 2023 (motorettagroup.com) is partly to ensure they meet standards and maybe to account for them officially, though for the unregistered ones, oversight is less.

In sum, e-scooters can contribute to Bulgaria’s climate goals and cleaner cities if they truly replace car use. They likely do so to an extent, but maximizing that requires integration (e.g., encouraging people to scooter to a transit hub instead of driving) and continuous improvement in operations.

Cost of Accidents and Public Health

Accidents involving e-scooters carry economic costs. Each injury means medical treatment costs (ambulances, hospital stays, rehabilitation). In Bulgaria’s universal healthcare system, much of that is borne by the state (i.e., taxpayers). While a simple fall might only incur minor treatment, serious head injuries or orthopedic surgeries can be expensive. If the frequency of such trauma increases due to e-scooters, it strains health resources or diverts them from other needs. There haven’t been publicized figures for the aggregate cost of scooter injuries in Bulgaria, but given 192 people injured in 7 months of 2024, we can infer dozens of hospitalizations. If each hospitalization costs several thousand leva, the public health cost could be substantial over time.

There’s also the cost in terms of lost productivity – many victims are young, working-age individuals. An injured rider might be out of work for weeks, impacting businesses and families. In fatal cases, the societal cost is immense (lost future earnings, the burden on families). These are hard to quantify but are part of the socio-economic impact. Some countries attempt to quantify “cost per traffic injury/fatality” (EU average values exist), which would allow an estimate of how much e-scooter accidents have “cost” Bulgaria in monetary terms. Even without exact numbers, it’s recognized that improving safety (reducing accidents) has not just moral but clear economic benefits.

It’s worth noting that no-fault accident insurance is absent. If a rider injures themselves, they rely on their health insurance. If they injure someone else or damage property, there might be lawsuits. Without mandatory third-party insurance, a pedestrian hit by a scooter may need to sue the rider for damages, which is an inefficient system. In a few cases, the rental companies have covered damages (some have insurance for their operations), but that’s not guaranteed. This lack can impose unforeseen costs on victims or on public funds (if the victim’s medical care and any disability is shouldered by the state). Other industries – say, automobiles – internalize these costs through insurance premiums. E-scooters haven’t yet.

There’s also a public health angle: E-scooters provide a form of active mobility, though not as much exercise as cycling or walking. Still, balancing on a scooter engages core and limb muscles, and riding outside has mental health benefits. But if scooters replace walking, one could argue they reduce physical activity marginally. This is a nuanced aspect: ideally, scooters replace car trips (good: slightly more exercise than sitting in a car, plus less pollution) rather than replacing walking (bad: less exercise). It’s hard to tell in Bulgaria how that trade-off nets out. Given that not everyone would walk long distances anyway, likely many scooter rides replace what would have been short car/taxi rides, so maybe a slight positive for health overall (plus reduction in air pollution is a health benefit for all). There haven’t been Bulgaria-specific studies, so this remains speculative.

Municipal Costs and Response

City governments have had to respond to the scooter wave, which involves administrative and enforcement costs. Sofia Municipality staff spent time drafting the new ordinance, coordinating with companies, and handling citizen complaints. They also likely incur costs in marking parking zones, installing signage (e.g., “No e-scooters” signs in certain areas), and possibly allocating space for scooter parking (removing some car parking or using sidewalk space – an opportunity cost). Enforcement falls partly on police (national), but also on municipal police who handle things like sidewalk obstructions. Sofia’s new rules impose fines on companies if they don’t clear scooters in time (novinite.com), implying the city might pick them up and store them (logistical cost) if left unattended.

On the flip side, some municipalities might seek to raise revenue from scooters eventually, for instance by charging operators fees for using public space. Cities like London charge per-scooter fees or profit-sharing. Sofia hasn’t implemented fees yet, but it could. Right now, enforcement is likely costing more than any revenue (since fines are low and sporadic). Another cost is infrastructure adaptation: building more bike lanes to accommodate scooters is a capital expense, but one could say scooters provide impetus to accelerate bike infrastructure that benefits overall mobility.

Interestingly, e-scooters might reduce some costs: fewer cars can mean less road wear (scooters are light and cause negligible wear compared to cars/trucks). They also take up far less space than cars when parked or moving, so they can reduce the need for expanding roads or parking facilities if they truly replace car usage for some trips. These savings are long-term and diffuse, though.

There’s also the question of integration with public transport. If transit agencies coordinate with scooter firms (for example, having scooter parking at metro stations or including scooter rentals in mobility apps), it could enhance the overall system. In some cities, transit authorities incur costs to provide charging docks or to subsidize scooter rides to transit. In Bulgaria, there is no known direct integration yet (no combined ticketing or such), so no costs there, but it remains a possibility for future “Mobility as a Service” platforms.

Economic Opportunities

On the positive side, the e-scooter boom has created jobs and business opportunities in Bulgaria. Each scooter company hires local operations teams: technicians to repair scooters, drivers to redistribute or charge them (though some use gig workers or subcontractors), marketing and community managers, etc. Hobo, as a startup, received angel investment and provided work for its team of developers and logistics staff (trendingtopics.eu). Even the international companies contribute to the local economy by employing people (Bird’s partner BRUM, Lime’s local unit, Bolt’s local mobility division, etc.). These are mostly urban jobs, often entry-level (like charger pickup roles) but also skilled (mechanics, city managers). The scale is not huge – perhaps dozens of jobs per operator – but not trivial either.

Local entrepreneurship has been spurred: aside from Hobo and Shareascoot, we see small businesses like scooter repair shops or accessory sellers popping up. For example, more stores now sell helmets and scooter spare parts as private ownership has grown. Tourism also gains a minor boost: many visitors enjoy renting scooters to tour Sofia or Varna, and some tour companies might incorporate e-scooters into guided city tours. Satisfied tourists spread the word, potentially attracting more visitors interested in easy mobility.

In the mobility sector at large, e-scooters have nudged cities to innovate and think about smart city solutions. This can have spillover benefits – data collected can inform traffic management, and the experience might pave the way for other electric micro-vehicles (like e-bikes, which are also growing).

From a socio-economic perspective, providing affordable transport has equity implications: If managed well, e-scooters can complement public transit and provide low-cost mobility to those who don’t own cars (which in Bulgaria is a fair number of people, especially younger and lower-income individuals). That can improve access to jobs or education by making it easier to reach transit stops or go to places not well-served by transit. However, if not managed, they could also primarily serve the well-off (if concentrated in rich areas and mainly used by people with smartphones and bank cards). Cities will have to ensure a balanced deployment to harness the equity benefits.

Lastly, consider substitution effects: the presence of e-scooters might reduce demand for some other services – for instance, short taxi rides or even illegal gypsy cabs might decline if scooters provide an alternative. This can have economic implications for those industries (taxi drivers might lose a bit of income). However, given that scooters are mostly for very short distances, the impact on traditional transport jobs is likely minimal.

Overall, the economic impact is a mixed bag: e-scooters bring innovation, jobs, potentially tourism and transit benefits, but also impose costs through accidents and required city management. Suppose Bulgaria can maximize the positives (through good integration and perhaps local manufacturing or tech development) and minimize the negatives (safety issues, cleanup costs). In that case, the net socio-economic effect will be positive.

Comparison with Other Countries: Regulation and Integration

To put Bulgaria’s e-scooter saga in context, it’s helpful to compare how other countries have regulated and integrated e-scooters into urban transport. Europe in particular has seen a range of approaches, from permissive to highly restrictive. We’ll look at a few representative examples – France, Germany, the Netherlands, as well as outside Europe like the US and Singapore – to see what Bulgaria might learn.

France: From Boom to Backlash

France was one of the first European countries hit by the e-scooter wave (Paris famously had uncontrolled growth around 2018). The French government responded with national regulations in October 2019, similar in spirit to Bulgaria’s but with some differences:

- Min. Age 14, speed limit 25 km/h (evz.de) (initially France allowed age 12, but later raised to 14).

- Helmet not mandatory for e-scooters (just recommended), except they have a general rule that all cyclists under 12 must wear helmets, but since under 14 can’t ride scooters, effectively no helmet law for riders. So Bulgaria actually has a stricter helmet rule (for minors) than France at present.

- Where to ride: Forbidden on sidewalks (unless pushing); allowed on bike lanes and roads ≤50 km/h – nearly identical to BG’s rules. France also allows riding in pedestrian zones at walking speed if the local authority permits.

- Equipment: mandatory lights, brakes, reflectors, bell, and interestingly prohibits wearing headphones while riding (a safety measure to keep riders alert). Bulgaria’s law does not explicitly ban headphones, which could be something to consider (distracted riding).

- Insurance: France requires each e-scooter (private) to have third-party liability insurance. Many French people cover this under their home insurance liability clause.

- Enforcement: France set hefty fines – €135 for riding on the sidewalk, €1500 for going over 25 km/h (which could even imply confiscation of the device if modified), and potential confiscation and a year in jail for extreme reckless behavior. These are far stricter consequences than in BG. They treat egregious scooter misuse almost like reckless driving of a car.

- Outcome: Despite these rules, Paris in particular continued to suffer from scooter congestion and accidents. By 2022, public sentiment in Paris turned very negative (complaints about scooters “dumped everywhere” and accidents, including a high-profile case of a pedestrian killed by a scooter). The city held a referendum in 2023 where nearly 90% of voters who participated chose to ban rental e-scooters (euronews.com). This took effect in September 2023, making Paris the first EU capital to ban shared scooters entirely. Private scooters are still allowed under national law, but the ban on rentals in Paris (and some other French cities considering similar moves) was a wake-up call. Essentially, France had a boom, then a backlash due to quality of life concerns.

- Other French cities like Lyon, Marseille, etc., didn’t ban but imposed stricter controls (limiting the number of operators, designated parking, etc.).

Lesson for Bulgaria: France’s experience shows the importance of managing the negative externalities. Even with rules, enforcement in Paris was lacking until citizens had had enough. Sofia and others might avoid that fate by proactively enforcing parking rules, limiting clutter, and maintaining public goodwill. The insurance mandate in France is something Bulgaria could emulate to ensure accident victims are covered. Also, France’s headphone ban and high fines for misconduct could be ideas to strengthen BG regulations.

Germany: Controlled Integration with Insurance and Type Approval

Germany legalized e-scooters in mid-2019 with a national regulation that is often cited as a balanced approach:

- Speed limit 20 km/h (not 25)evz.de. Germany deliberately set a slightly lower max speed, thinking it would improve safety.

- Minimum age 14 (same as BG for full use).

- No helmet requirement (just recommended, like most places).

- Where to ride: On bike lanes or roads if no bike lane, but never on sidewalks. Germany has ample cycling infrastructure in many cities, making this feasible. Bulgaria’s law is identical on this point (no sidewalks, use bike lanes/roads).

- Device requirements: Germany treats e-scooters like a new vehicle category requiring a general operating permit (ABE). Scooters must have certain features (two independent brakes, lights, bell, reflectors) and, crucially, must be certified and issued an “operating license” by the authorities. If someone buys an uncertified model or modifies one to go faster, it’s illegal on public roads. Each scooter must also display an insurance plate (sticker) signifying it has liability insurance. Riding without this small license plate sticker is an offense (roughly €40 fine). This effectively registers the scooter with an insurer, though not with the state DMV.

- Insurance: Mandatory third-party liability insurance for any e-scooter on public roads, as mentioned. Most shared operators handle this for their fleet; private owners must get an insurance policy (~€30/year in Germany).

- Enforcement & Penalties: Germany is strict with DUI on e-scooters – the same BAC limits as for driving a car (0.5‰ for a fine, 1.1‰ is a criminal offense). In fact, many Germans lost their driver’s licenses due to drunk scooter riding, since the offenses transfer to their driving record. This has had a sobering effect on the culture. Fines for traffic violations are similar to those for minor stuff (e.g., €25 for running a red light on a bicycle/e-scooter if no endangerment, but if endangering others, it goes up to €100+). There were also high-profile crackdowns on improper parking and mass retrieval of scooters from rivers.

- German cities often require scooters to be parked upright on the curb, not blocking paths, and some have created parking zones in places like Berlin and Hamburg, operators voluntarily or at the city’s request use technology to limit speeds or restrict zones (e.g., slow to walking speed in pedestrian-heavy areas, or no-go zones around government buildings).

- Result: Germany has integrated e-scooters fairly successfully without major bans, though injuries have occurred. By late 2021, Germany recorded ~1150 serious injuries and several dozen deaths related to e-scooters since legalization – not insignificant, but still a small fraction of overall traffic accidents. Public acceptance is mixed but hasn’t boiled over as in Paris. The clear rules (especially insurance and identification) likely helped accountability.

Lessons for Bulgaria: Germany’s requirement of mandatory insurance and identifiable scooters (via a plate) stands out. In Bulgaria, scooters have no visible ID, making it hard to report a reckless rider unless you catch them. If insurance and some form of registration were required, riders might behave more cautiously, and victims would have recourse. That said, imposing registration in Bulgaria would be a big shift, essentially treating scooters like mopeds – something the current law avoided for simplicity. Another lesson is strict DUI treatment: Bulgaria’s 20 BGN fine is lax compared to Germany, where you can actually get a criminal record for scootering very drunk. Aligning DUI rules for scooters with those for cars (especially for high BAC levels) could be considered to deter extremely risky behavior.

Also, Germany’s type approval ensures a level of vehicle safety (brakes, etc.). Bulgaria’s law calls for brakes and lights, but doesn’t have a system of pre-approving models. It relies on users and importers to abide by the letter of the equipment law. That means potentially substandard e-scooters could be on the road (though in practice, most are decent). Perhaps as the market matures, Bulgaria could enforce that only CE-certified or EU-conforming scooters can be sold/used.

The Netherlands: Ultra-Strict, Prioritizing Safety

The Netherlands took a notably strict stance: they essentially ban most e-scooters on public roads unless they are explicitly approved as motorized bicycles (snorfiets). The Dutch consider anything without pedals and with a motor >100W as a moped that requires approval. As of 2023, very few stand-up scooters met their criteria (some Segway-like devices were approved). So while the Netherlands has world-class bike lanes, you won’t see the free-for-all scooter sharing there. Some Dutch cities ran trials with specific devices that have saddle seats, treating them as mopeds with license plates and insurance.

This strict approach stems from Dutch road safety philosophy and also the fact that they already have extremely high cycling rates – they didn’t want to disrupt that with scooters on bike paths, possibly causing new hazards. Essentially, they said: if it’s not safe enough by design (stability) to be a bicycle, we won’t allow it unless it’s regulated as a moped.