From the time of the American psychologist James Cattell in the 1880s, the scientific investigation of reading has been a fascinating and continuously evolving field. Cattell’s groundbreaking work, employing mechanical methods to measure the seemingly insignificant, set the foundation for the scientific exploration of reading. These almost imperceptible actions, like the brief pauses our eyes make while scanning a line of text, were deemed to be of profound significance. Fast forward to the present, our tools have advanced from mechanical devices to high-resolution neuroimaging scanners. Yet, in its complexity and elegance, reading remains a wonder and extensive study subject.

Eye Movements in Reading

The act of reading engages an intricate sequence of eye movements. Our eyes do not glide smoothly across the text during a casual read. Instead, they make short, rapid movements known as saccades, punctuated by brief fixation periods. Research has shown that our eyes make about 1-5 saccades per second while reading, and each fixation lasts approximately 200-300 milliseconds.

In a single fixation, our visual field encompasses about 7-9 characters to the right and left of fixation in English text. However, the span might be smaller in languages such as Chinese, which has a denser orthography. The text’s complexity and familiarity can also affect our perceptual span and reading speed.

Research has also revealed the “optimal viewing position” phenomenon. In left-to-right reading languages like English, words are recognized most quickly when our eyes are fixated just left of the word center.

Interestingly, our eyes don’t land on every word when we read. The likelihood of skipping a word depends on several factors, such as word length, frequency, and predictability in context. For instance, short, frequent words are more likely to be skipped, particularly if they are predictable from the sentence context.

Though seemingly simple, these insights into eye movements reveal the efficient and optimized nature of the reading process, highlighting how our eyes and brain work together to transform symbols into meaning. However, these eye movements are just the start of the complex process of reading. The cognitive journey from recognizing letters to understanding text is profound and has multiple interconnected stages.

The Neurobiology of Reading

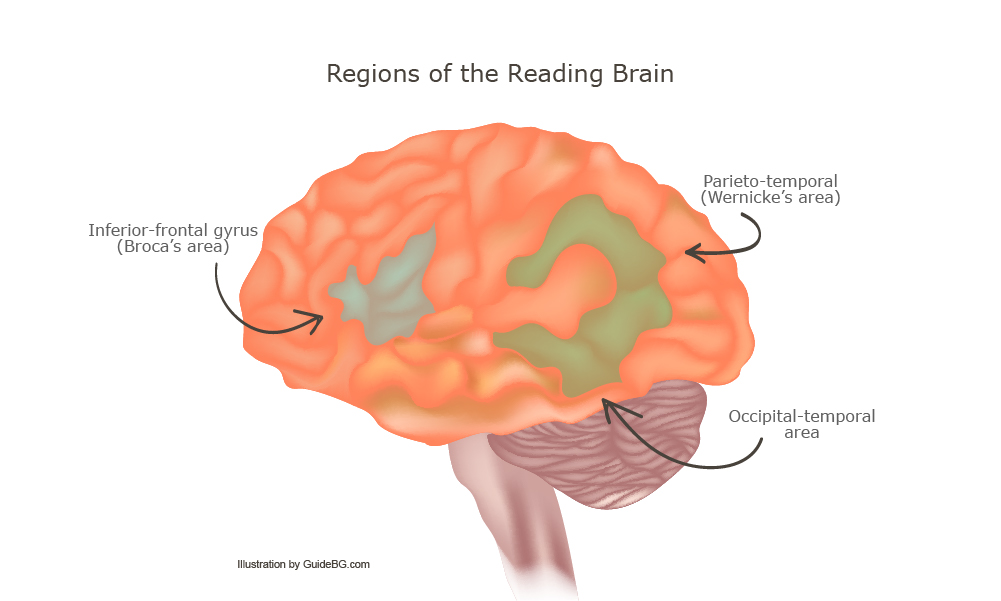

Reading engages a vast network of brain regions, from the initial processing of visual stimuli to the ultimate comprehension of text. Neuroimaging studies have provided crucial insights into these regions’ roles in decoding written language.

When our eyes fixate on text, the visual information is processed by the primary visual cortex located in the Occipital lobe. The information is sent to other brain parts for more complex processing.

Three critical areas of the brain play significant roles in the reading process. Firstly, the occipito-temporal area, often dubbed the brain’s “letterbox,” helps recognize letters and familiar words as whole units or “sight words.” The rapid recognition of these words is vital for fluent reading.

Secondly, the Parieto-temporal (Wernicke’s area) region aids in sounding out unfamiliar words or pseudowords. It’s involved in the phonological processing of written language, linking the visual representation of words to their corresponding sounds.

Thirdly, the anterior region comprising the Broca’s area and the inferior frontal gyrus is responsible for comprehending and interpreting the text. Here, the brain processes syntax (sentence structure) and semantics (meaning), helping us derive meaning from the text.

It’s important to note that these areas do not work in isolation. The brain’s reading network is interconnected, with constant communication between these areas. Neuroimaging studies using fMRI and DTI have shown robust connectivity within this network during reading tasks.

Moreover, individual differences in reading ability have been linked to variations in the structure and function of these brain regions. For instance, studies have found that skilled readers often show higher activity in the occipito-temporal area and more robust connectivity within the reading network than less skilled readers.

The Process of Reading

Reading is an intricate cognitive process involving various interconnected stages, from visual recognition of letters to constructing meaning. Let’s delve into the steps of this complex task.

Visual Processing and Word Recognition

Reading starts with the visual processing of symbols and letters. When our eyes fixate on text, the visual information is first processed in the primary visual cortex. This information is then passed on to other brain areas like the occipito-temporal cortex, which helps us rapidly recognize familiar words as whole units.

Phonological Processing

Simultaneously, the visual representation of words is linked to their corresponding sounds in a process known as phonological processing. This crucial step, primarily facilitated by the parieto-temporal area, enables us to sound out unfamiliar words and aids in learning new words.

Syntactic and Semantic Processing

After recognizing the words, our brains process the sentence structure and the words’ meanings. Broca’s area and the inferior frontal gyrus play significant roles in syntactic (understanding how words form sentences) and semantic processing (deriving meaning from words and sentences).

Text Comprehension and Memory

Finally, the derived meaning is integrated with our prior knowledge and context, leading to the comprehension of the text. The prefrontal cortex, involved in executive functions, aids in this higher-level processing, while regions like the hippocampus help store the learned information in our long-term memory.

This cognitive journey is a testament to the complexity and efficiency of our brains. However, reading doesn’t always go smoothly for everyone. Understanding how reading skills are acquired and the difficulties some people face is crucial.

Reading Acquisition and Learning

Learning to read is a significant milestone in child development that requires integrating various cognitive, linguistic, and motor skills. It’s a complex process that often starts long before a child enters school.

Early Literacy Development

Early literacy development begins with recognizing sounds, a skill known as phonemic awareness. This ability to hear and manipulate the sounds in spoken language lays the foundation for associating sounds with written symbols or letters, a concept known as the alphabetic principle.

In preschool years, exposure to print and the alphabet and developing oral language skills play a significant role in early literacy. Children start recognizing letters, associating them with sounds, and gradually begin to read simple words.

The Role of Instruction and Practice

Reading instruction and practice are crucial in developing fluency and comprehension skills. Decoding strategies, such as phonics instruction, help children learn the relationship between letters and sounds. With practice, children start recognizing words more quickly, a skill known as automaticity, which is crucial for fluency.

As children become more fluent readers, their focus shifts from decoding to understanding the text. Comprehension skills, such as making predictions, drawing inferences, and summarizing, are taught to enhance understanding.

Reading Difficulties and Disorders

Despite instruction and practice, some children struggle with reading. Difficulties with accurate or fluent word recognition, poor spelling, and decoding abilities characterize dyslexia. Research suggests that dyslexia is associated with deficits in the phonological component of language and often runs in families.

Research also indicates that dyslexic readers show different patterns of brain activity compared to typical readers. They often show less activity in the occipito-temporal area and more activity in the frontal regions, possibly indicating a reliance on more effortful reading strategies.

Reading vs. Visual Learning

As technology evolves, so do the mediums through which we consume information. While traditional reading remains integral to learning, visual media, such as videos and infographics, are increasingly used as educational tools. Let’s delve into the science behind these two learning methods.

Reading: A Deep Cognitive Engagement

Reading engages our brains in unique ways. It activates the areas associated with language processing and comprehension and requires active involvement in constructing meaning from the text. Reading promotes deep thinking, improves focus and concentration, and strengthens our ability to understand complex ideas.

Moreover, reading at one’s own pace allows for better understanding and retention. A study in the Journal of Educational Psychology found that students who read texts instead of watching videos performed better in following instructions.

Visual Learning: Stimulating and Interactive

On the other hand, visual learning, such as watching videos, stimulates regions involved in processing visual and auditory stimuli. Videos can be more engaging for some learners, especially for complex topics that benefit from visual demonstrations.

According to a study published in the “Journal of Visualized Experiments”, students who learned through video demonstrations significantly outperformed those who learned through traditional laboratory manuals. It suggested that video learning could provide richer context and visual cues, aiding understanding and retention.

Balancing the Two

Both reading and visual learning offer unique advantages, and the choice between the two often depends on the learning context and individual learner’s preferences. Balancing the use of these mediums can optimize learning outcomes. For instance, combining reading with complementary visuals or videos can enhance understanding and retention, offering learners the best of both worlds.

The Impact of Digital Technology on Reading

The way we read has dramatically changed in the era of digital technology. Digital screens, electronic books, and online content have become increasingly prevalent, affecting our reading habits and skills.

E-Books and Digital Reading

Digital readers have transformed book access, allowing portability and accessibility like never before. However, their impact on reading skills is mixed. Some studies suggest that reading on screens might slow reading speed and reduce comprehension, possibly due to the lack of tactile experience and spatial navigation that print reading provides.

However, other studies suggest that digital reading can be equally effective if readers are accustomed to the medium. For instance, a study published in “Computers & Education” found no significant difference in comprehension between digital and print reading for experienced digital readers.

Online Reading: Skimming and Multitasking

Online reading often involves more than just decoding text. It requires navigation skills, decision-making, and, often, multitasking. Research suggests that we tend to read online content in an “F” pattern, focusing on the top and left sides of the screen. Online reading promotes skimming, with readers jumping through texts and searching for relevant information.

While this can enhance information-seeking skills, it may also affect deep reading. A study in the journal “Memory & Cognition” found that participants who read a text in a controlled, linear manner had better comprehension than those who engaged in non-linear reading (skipping and scanning).

The Role of Digital Literacy

As digital reading becomes increasingly prevalent, the importance of digital literacy, the ability to find, evaluate, and effectively use online information, becomes evident. Developing these skills can help optimize the benefits of digital technology while minimizing potential drawbacks.

Future of Reading Research

As we unravel the intricate reading process, certain areas warrant further exploration, promising exciting advancements in reading research.

Understanding Individual Differences

While significant strides have been made in identifying the neural and cognitive processes involved in reading, understanding the substantial differences in reading ability remains challenging. Future research on the genetic, neurobiological, and environmental factors contributing to these differences could shed light on this complexity.

Leveraging Machine Learning and AI

With the advent of advanced technologies like machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI), there’s potential to glean deeper insights into reading science. AI can help model complex cognitive processes involved in reading and could potentially be used to develop sophisticated reading instruction and intervention tools.

The Influence of Digital Technology

The impact of digital technology on reading is a burgeoning field of research. As screen-based reading becomes increasingly common, it is crucial to understand its effects on reading skills, comprehension, and cognitive development. The design of digital reading environments and how they can be optimized to support deep reading is another promising research area.

Multilingualism and Reading

As the world becomes more interconnected, multilingualism is increasingly common. Understanding how reading skills transfer across languages, how multiple languages interact in the brain, and how best to teach reading in multilingual contexts are all essential research directions.

Imagery in Reading versus Visual Learning

The magic of the written word lies in its ability to ignite the reader’s imagination, transport them to far-off lands, or make them feel a character’s emotions. This immersive experience hinges on creating mental images, a cognitive process known as imagery. In contrast, like watching a video, visual learning provides explicit visual and auditory stimuli, directly offering sensory experiences. Let’s explore how these two learning methods engage our brains and senses differently.

Reading: An Imaginative Journey

Reading activates various regions of the brain associated with language processing and comprehension. However, reading goes beyond these cognitive processes – it involves the reader’s active engagement in creating mental representations of the described scenes, characters, and events.

A study published in the “Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience” found that reading descriptions of smells activated the olfactory cortex, the area responsible for smell processing, suggesting that reading can evoke sensory experiences similar to real-world experiences.

When we read, we’re not just passive receivers of information; our brains actively construct images, sounds, and even smells from the text, bringing the narrative to life. Creating mental imagery can boost memory and comprehension and foster a deeper emotional connection with the text.

Visual Learning: A Direct Sensory Experience

On the other hand, visual learning, such as watching a video, provides a direct sensory experience. Videos integrate visual and auditory stimuli, offering detailed depictions of scenes, characters, or processes. They can show dynamic changes, close-ups, or different angles, offering a rich and engaging learning experience.

For example, a video about the inner workings of a cell can show the movements of organelles, changes in cell shape, and interactions between different molecules. Such explicit visualizations can help learners grasp complex processes more quickly than reading about them.

However, videos provide explicit visual and auditory stimuli, so they may require less active mental construction than reading. An “Applied Cognitive Psychology” study found that reading elicited more vivid and emotionally engaging mental images than watching videos.

Striking a Balance

While reading and visual learning engage our senses uniquely, they offer different learning experiences. Reading fosters the active construction of mental imagery, engaging the imagination and potentially boosting memory and comprehension. Visual learning provides explicit visual and auditory stimuli, offering an engaging and accessible understanding of complex information.

The choice between the two often depends on the learning context and individual learner’s preferences. A balanced use of these methods, such as reading a text and watching a related video, can offer a rich, multi-faceted learning experience, engaging different cognitive processes and catering to diverse learning styles.

Final Words

The science of reading, from its early investigations in the 1880s to modern neuroimaging studies, offers profound insights into one of our most vital cognitive skills. The intricate dance of eye movements, the symphony of neural activity, and the complex cognitive processes underlying reading reveal how we make sense of the text and how our brains make sense of the world.

Our understanding of reading has critical implications. In education, it can inform effective reading instruction and intervention strategies. In technology, it can guide the design of digital reading environments. And in society, it can help us navigate the evolving landscape of literacy in the digital age.

As we continue to unravel the mysteries of reading, we are reminded of Carl Sagan’s words: “Writing is perhaps the greatest of human inventions, binding together people, citizens of distant epochs, who never knew one another. Books break the shackles of time – proof that humans can work magic”. The science of reading is, indeed, a testament to this magic.

Appendix: The Importance of Offline Intellectual Engagement

In the digitally connected world of the 21st century, offline intellectual engagement, whether through reading a physical book or participating in board games, plays an essential role in cognitive and social development for both children and adults.

Reading and Cognitive Development

Engaging with physical books offers a different experience compared to digital reading. It involves the tactile experience of holding a book and turning its pages, which enhances sensory involvement and fosters a deeper connection with the text. Reading from print can also aid in spatial navigation, allowing readers to remember where information is located on a page or in the book, aiding comprehension and memory.

Physical books minimize digital distractions, promoting deep reading – the focused, immersive reading needed to understand complex narratives or arguments. Deep reading cultivates critical thinking, empathy, and imagination as readers have to infer characters’ feelings or predict plot developments, fostering emotional intelligence and creativity.

Offline Games and Cognitive Skills

Offline games, such as board games, puzzles, and card games, offer unique cognitive benefits. They stimulate strategic thinking, problem-solving skills, and mental flexibility as players adapt to changing game scenarios. These games also foster memory and concentration, as players need to remember rules, track past moves, or hold multiple pieces of information in their minds.

UnpluggedPlaytime

A wonderland of screen-free fun where imagination reigns supreme! Explore our treasure trove of printable offline games – crosswords, spot-the-differences, origami, word hunts, drawing tutorials, and more – all designed to spark curiosity and creativity in young minds. Get ready for an offline adventure like no other!

Moreover, many games require numerical and language skills, aiding in developing and practicing these academic skills. For instance, word games like Scrabble can enhance vocabulary and spelling, while games like Chess can promote spatial and mathematical skills.

Social and Emotional Skills

Offline reading and games also foster social and emotional skills. Reading books about different cultures, experiences, or perspectives can cultivate empathy and understanding. Shared reading, like a parent reading to a child or a book club discussion, can foster social bonds and improve communication skills.

Offline games often involve playing with others, fostering social interaction and cooperation. They teach essential social skills like taking turns, following rules, and gracefully dealing with winning or losing. Moreover, shared laughter and competition can create memorable experiences and deepen social connections.

The Balance of Offline and Online Engagement

While online activities offer unique learning opportunities and benefits, balancing online engagement with offline intellectual activities can lead to optimal cognitive and social development. Ensuring this balance in the ever-evolving digital landscape is essential to education and personal growth.

Offline intellectual engagement is more than just a break from the digital world. It is an avenue for deep cognitive, social, and emotional development. Whether it’s the magic of immersing oneself in a good book or the thrill of strategizing in a board game, these offline activities remind us that the original play is often the best.

To encourage further reading, here is a comprehensive list of the primary sources and cited articles used throughout the construction of this article:

- “Reading: the Functional Anatomy of Literacy” – Oxford University Press.

- “Phonological awareness, reading, and reading acquisition: A tutorial” – David L. Share, 2018.

- “Visual Word Recognition Volume 1: Models and Methods, Orthography and Phonology” – Manuel Perea and Jon Andoni Duñabeitia, 2019.

- “Reading: Breaking the Page Barrier” – Stanislas Dehaene, 2009.

- “Reading in the brain: the new science of how we read” – Stanislas Dehaene, 2009.

- “Decoding the neuroanatomical basis of reading ability: a multivoxel morphometric study” – Hoeft et al., 2007.

- “Dyslexia: a new synergy between education and cognitive neuroscience” – Shaywitz & Shaywitz, 2008.

- “The science of reading: A handbook” – Snowling, M.J. & Hulme, C, 2005.

- “The Effect of Reading a Short Passage of Literary Fiction on Theory of Mind in Comparison to Reading Non-fiction” – Koopman, E., & Hakemulder, F, 2015.

- “Brain imaging of reading” – Inhoff, A.W., & Topolski, R, 1994.

- “Decoding the reading brain” – Starrfelt, R., & Behrmann, M, 2011.

- “The science of reading: a handbook” – Snowling, M.J. & Hulme, C, 2005.

This article was inspired by Adrian Johns’ “The Science of Reading” book, Univ. Chicago Press (2023)