Imagine sitting at a conference table with colleagues from five countries, all eager to succeed but speaking subtly different cultural “languages.” In today’s borderless business environment, nearly 89% of corporate employees serve on at least one global team. However, what happens when cultural misalignment turns that wealth of diversity into a breeding ground for misunderstandings? This article unpacks how to navigate cross-cultural conflict resolution in the workplace – an essential skill for managers and teams striving to achieve high performance, inclusivity, and a competitive edge.

We’ll explore why conflicts arise in multicultural settings, dive into the psychology behind them, and present strategies to resolve these tensions effectively. Along the way, we’ll weave in renowned cultural theories like Hofstede’s dimensions and conflict management models such as Thomas-Kilmann’s conflict modes, all supported by real-world examples and recent research. By the end, you’ll be equipped with actionable insights to transform cultural differences into collaboration opportunities and drive team performance in an era where inclusive teams are over 35% more productive and diverse teams make better decisions 87% of the time.

What You’ll Learn:

- Why Cross-Cultural Conflicts Occur: The role of communication styles, power distance, and cultural values in sparking misunderstandings.

- The Psychology of Culture Clashes: How cognitive biases and emotional triggers escalate conflicts in diverse teams.

- Effective Conflict Resolution Strategies: Practical approaches for building cultural awareness, adapting communication, and finding common ground.

- Cultural Frameworks in Action: Integrating Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (like power distance and individualism) and Thomas-Kilmann’s conflict modes (competing, collaborating, avoiding, accommodating, compromising) for nuanced strategies.

- Real-World Examples: Case studies from industries including pharma, tech, and remote teams showcasing conflict transformation.

- Modern Relevance: A conclusion linking cross-cultural conflict resolution to today’s DEI (Diversity, Equity & Inclusion) initiatives and the performance gains of inclusive teams.

What’s on the Agenda

- What Causes Cross-Cultural Conflicts?

- The Psychology of Cross-Cultural Conflict

- Strategies for Effective Cross-Cultural Conflict Resolution

- Benefits of Resolving Cross-Cultural Conflicts Effectively

- Real-World Examples of Cross-Cultural Conflict Resolution

- Turning Cross-Cultural Challenges into Opportunities

- Deepening Your Understanding of Cross-Cultural Conflict Resolution

What Causes Cross-Cultural Conflicts?

Cross-cultural conflicts arise when differences in values, communication styles, and workplace norms create friction among team members. In a globalized workplace – whether it’s a pharmaceutical company running trials across continents or a tech startup with remote developers worldwide – these conflicts can delay projects, strain relationships, and hinder innovation. Recognizing the root causes is the first step in resolving them.

Communication Styles: High-Context vs. Low-Context Cultures

One fundamental cause of cross-cultural conflict is contrasting communication styles. Anthropologist Edward T. Hall described cultures as being on a spectrum from high-context to low-context, shaping how people convey and interpret messages:

- High-Context Cultures (e.g., Bulgaria, Japan) – Communication is indirect and implicit. Much is left unsaid, relying on tone, body language, and shared understanding. Feedback and disagreements are often wrapped in diplomatic language, requiring the listener to “read between the lines.”

- Low-Context Cultures (e.g., United States, Germany) – Communication is direct and explicit. Messages are conveyed with clarity, leaving little room for interpretation. Feedback is straightforward, and silence or vagueness can be interpreted as a lack of transparency.

Example: A Bulgarian project coordinator (from a high-context culture) might say, “We might need to revisit some of the trial procedures soon,” as a polite hint that changes are urgently needed. Their American counterpart (from a low-context culture) might miss the urgency entirely, because in the U.S., one might say directly, “This protocol is outdated – we need to change it by Friday.” The misalignment between implied meaning and explicit message can create frustration, with each party misreading the other’s intent.

Perceptions of Hierarchy and Authority

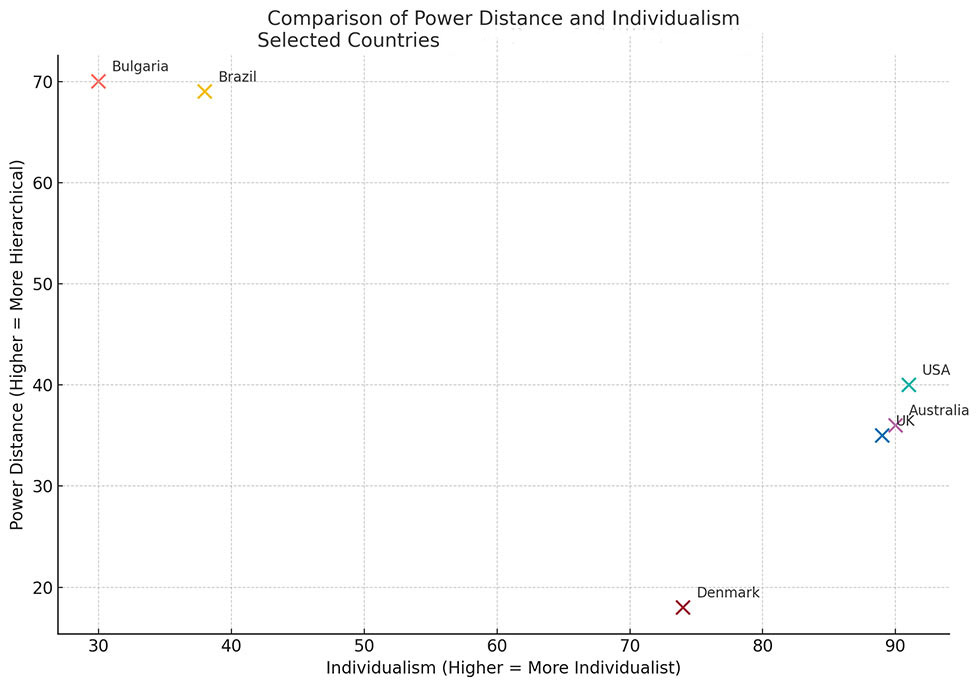

Another conflict trigger is how different cultures view hierarchy and power distance, a concept popularized by Geert Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory. Power Distance refers to the extent to which a society accepts unequal power distribution:

- High Power Distance Cultures (e.g., Bulgaria, India) – Clear hierarchies are respected. Managers are expected to give top-down directives, and subordinates may hesitate to challenge or question decisions. According to Hofstede’s research, Bulgaria’s relatively high power distance score indicates that hierarchical order is largely accepted as-is, with centralization common.

- Low Power Distance Cultures (e.g., Denmark, USA) – Hierarchies exist but are downplayed. Open dialogue across levels is encouraged, and it’s more acceptable – even encouraged – to question or offer feedback to a superior. For instance, Denmark’s low power distance fosters egalitarian workplaces where even junior employees openly voice ideas.

Example: A Bulgarian team working with a Danish consultant might experience friction. The Bulgarian employees, used to a hierarchical structure, could feel that the consultant’s insistence on group consensus undermines their manager’s authority. The Danish consultant, on the other hand, might view Bulgaria’s top-down approach as outdated or overly rigid, not understanding it’s rooted in cultural norms about respecting leadership. Neither side is “wrong” – they simply have different expectations about who should make decisions and how.

Conflict Avoidance vs. Confrontation

Cultures vary in their comfort with confronting conflict directly:

- Conflict-Avoidant Cultures (e.g., Bulgaria, Japan, China) – Prioritize harmony and face-saving. Disagreements are often handled privately or subtly to avoid public embarrassment or strained relationships. In such environments, an employee might avoid saying “no” explicitly or delay delivering bad news, hoping to resolve things quietly.

- Confrontational Cultures (e.g., USA, Israel, Germany) – Believe in addressing issues head-on as a path to quick resolution. Open debate and even constructive conflict are seen as healthy. An American manager might say, “Let’s hash out our differences now,” viewing a candid discussion as productive, not personal.

Example: A Bulgarian colleague might find an American coworker’s blunt feedback jarring, perhaps perceiving it as aggression, whereas the American feels they’re just being honest and efficient. Conversely, the American might view the Bulgarian’s polite hesitation to voice disagreement as a lack of initiative or clarity, not recognizing it as a culturally driven respect for harmony.

Values: Individualism vs. Collectivism

Cultural values around individual achievement vs. group harmony also shape conflict dynamics:

- Collectivist Cultures (e.g., Bulgaria, China, many Asian and Latin American countries) – Emphasize the group’s needs and consensus. Team success is paramount, and individuals might sacrifice personal preferences for group harmony. In conflict, someone from a collectivist background might seek solutions that benefit the team as a whole, even if it means compromising their own stance.

- Individualist Cultures (e.g., USA, UK, Australia) – Value personal autonomy and initiative. It’s expected that individuals look out for their own tasks and goals. In a conflict, team members might focus on reaching a solution that addresses their specific area of responsibility, trusting that if everyone handles their part, the whole will come together.

Example: In a tech startup’s design team, a Bulgarian designer (collectivist) might be waiting for a team meeting to address a product issue collectively, whereas an American engineer (individualist), noticing the bug, goes ahead to fix it on her own and announces the change later. The designer might feel excluded or slighted for not being consulted (valuing group involvement), while the engineer thinks she’s being proactive (valuing individual responsibility). Both perspectives have merit, yet the clash of approaches can spark conflict if not understood in a cultural context.

Different Views on Time and Deadlines

How teams perceive time management and deadlines often stems from cultural attitudes shaped over centuries, including whether a culture is monochronic or polychronic:

- Flexible-Time Cultures (Polychronic, e.g., Bulgaria, Italy, Latin America) – Relationship-building and quality may trump strict punctuality. Deadlines are seen as important guidelines, but there’s recognition that schedules might flex to accommodate changes, last-minute opportunities, or personal matters. The thinking is that time is a flowing river, not a set of individual “slots,” so multitasking and reprioritizing are common.

- Rigid-Time Cultures (Monochronic, e.g., Germany, USA, Switzerland) – Punctuality and schedule adherence are signs of professionalism and respect. Deadlines are taken very seriously – missing one can be seen as a failure or a breach of commitment. These cultures view time as a finite resource, segmented into blocks (meetings start/end on time, tasks are scheduled sequentially).

Example: Consider a cross-border project between a Bulgarian supplier and a German client. The Bulgarian team might extend the project timeline slightly to strengthen client relationships or ensure top-notch quality, believing the client values the improved outcome over strict timing. Meanwhile, the German team is growing anxious or frustrated because in their eyes, a deadline is a deadline – “late” equates to unreliability, regardless of reason. Without proactive communication, the German side might question the Bulgarian team’s professionalism, while the Bulgarian side might feel the Germans are being inflexible over a minor schedule change.

Understanding these differences is not about stereotyping but about recognizing colleagues’ origins. Cross-cultural conflicts often stem not from incompetence or ill intent, but from each person following a different “rule book” of unwritten cultural norms. The next challenge is learning how our minds process these differences, sometimes in ways that amplify tensions. Let’s delve into the psychology behind cross-cultural conflicts – the biases and emotional triggers that make a simple miscommunication feel like a major personal affront.

The Psychology of Cross-Cultural Conflict

Why do small cultural misalignments sometimes snowball into big problems? The answer lies in human psychology. When we encounter behaviors that don’t fit our expectations, our brains often fill the gaps with assumptions. In a high-pressure business context – think a regulatory deadline in pharma or a critical product launch in tech – these assumptions can turn a benign difference into a perceived threat. Understanding these psychological factors is key to diffusing conflict before it escalates.

Bias and Assumptions: The Subconscious Traps

Our brains use cognitive shortcuts (biases) to make sense of complex social interactions quickly. In cross-cultural settings, these shortcuts can misfire:

- Cultural Stereotypes: When lacking familiarity, people may default to oversimplified beliefs about another culture. A colleague might think, “All X culture people do [behavior],” which then colors interpretations of their actions. For instance, an American who’s heard “Bulgarians avoid confrontation” might misread a Bulgarian coworker’s thoughtful silence in a meeting as agreement (when perhaps they have concerns but are formulating them diplomatically).

- Projection Bias: Assuming others share your cultural norms. One might subconsciously expect their international teammates to behave “normally” (i.e., like they would). Example: A Swiss manager (from a punctual, process-driven culture) might find it baffling that a Brazilian partner joins a call 10 minutes late – he might assume they’re being disrespectful, when in Brazil it might be seen as an acceptable minor delay.

- Confirmation Bias: Once we have a belief, we tend to notice evidence that confirms it and overlook evidence against it. If you believe “German colleagues are rigid”, every strict process they enforce stands out as confirmation, while moments when they show flexibility may be shrugged off as exceptions.

These biases aren’t about being prejudiced; often they operate without our conscious awareness. They are mental shortcuts trying to protect us from uncertainty but can lead us astray.

Example: A Bulgarian employee working in the UK might hear a British colleague’s very direct critique and internally think, “They must not like me” – possibly tapping into a stereotype that Brits can be overly blunt. If the Bulgarians already feared that direct Western communication is aggressive, they’ll notice every sharp word (confirmation bias), and might miss all the friendly, collaborative gestures that contradict that stereotype. Meanwhile, the British colleague could hold a stereotype that Eastern European deference signals weakness or lack of ideas, so they might not invite the Bulgarian to brainstorming sessions, inadvertently reinforcing the very hesitation they’re noticing.

Emotional Triggers: When Misunderstandings Feel Personal

Cultural differences can poke emotional sore spots. Especially under stress – tight deadlines, high stakes deals – it’s easy for a simple cultural misstep to feel like a personal slight:

- Perceived Disrespect: Actions perfectly normal in one culture can be interpreted as rude in another. Example: Interrupting in meetings. In some fast-paced, dialogue-oriented cultures, interrupting means “I’m engaged and excited by your idea”, while in more restraint-oriented cultures, it’s seen as “You’re not letting me finish – how disrespectful!”.

- Unspoken Expectations: Each culture has unwritten rules about professional behavior – when they’re broken, people can feel offended without the other person even knowing. Example: A Bulgarian team member (from a collectivist culture) might expect important decisions to be discussed with the team (an unspoken norm). If their individualist British colleague makes an executive decision solo, the Bulgarians might feel the team was slighted. The Brit, meanwhile, thought they were being proactive and helpful, not realizing they trampled on a deeply held team value.

- Status and Face: In many cultures, maintaining dignity (“saving face”) is critical. Being called out publicly or proven wrong can trigger a strong emotional response. A normally calm person might react defensively or withdraw, not because of the issue itself, but because the way it was handled made them “lose face” in front of colleagues.

Example: Recall our earlier scenario of an American colleague interrupting a Bulgarian scientist in a meeting to ask a clarifying question. If the Bulgarian scientist’s cultural background treats interruptions as disrespectful, they might feel personally attacked or belittled, even though the American intended no harm. The emotional sting comes from a clash of norms – one person thinking, “I was just clarifying to help us all,” and the other feeling, “I wasn’t allowed to finish; I must not be respected.” Once emotions rise, conflicts can become harder to untangle because they’re no longer just about the topic but about hurt feelings.

The Role of Stress in Cross-Cultural Conflicts

High-pressure work environments act as a magnifier for cultural differences. When stress is high – be it a looming product launch, a financial quarter’s end, or a pharmaceutical trial phase – people have less patience and revert to their comfort zones.

In these moments, a small cultural misstep can act like a spark in a dry forest:

- Tight Deadlines & High Stakes: When the pressure is on, people may communicate more tersely or skip the usual pleasantries. Given the urgency, this might seem normal to a culturally attuned colleague; to someone less familiar, it might come off as unusually harsh or cold.

- Cognitive Load: Stress eats up mental energy. Team members may lack the bandwidth to empathize or adapt to others’ styles (“I don’t have time to explain in detail or soften my language, I just need this done!”). So, cultural sensitivities are often the first casualty under stress.

- Fight or Flight Responses: Psychological research shows that under stress, humans often exhibit primal conflict responses: some become more confrontational (fight), others withdraw or avoid (flight). These responses might align or clash with cultural norms. For instance, someone from a conflict-avoidant culture under extreme stress might completely shut down and avoid communication, whereas a normally calm person from a confrontational culture might suddenly become very direct or even abrasive. Each can shock the other.

Why this matters: Recognizing stress as an accelerant can help teams proactively add buffers. For example, if a diverse team knows a crunch time is coming, they might set explicit communication norms beforehand (“In the last week of the project, if I sound short, please know it’s just the rush; no offense intended”). Such meta-communication can preempt misinterpretations.

Unconscious Bias and Microaggressions

Beyond overt cultural differences, modern workplaces are grappling with microaggressions – subtle slights or snubs, often unintentional, that can alienate colleagues from different backgrounds. These often spring from unconscious biases:

- Unconscious Bias: Deeply ingrained, automatic judgments (positive or negative) about certain groups. Everyone has them, shaped by personal upbringing and societal narratives. In a global team, unconscious bias might manifest as assigning more importance to ideas presented by one culture over another, or assuming someone with a non-native accent “doesn’t understand the issue well” when they actually do.

- Microaggressions: Small actions or comments that make someone feel othered or lesser, even if no harm was meant. Examples include consistently mispronouncing someone’s name, making offhand “jokes” about stereotypes (“Oh, you’re from Country X, you must be good at math”), or overexplaining something to a qualified colleague because of an assumption they need extra help (often observed in cross-gender or cross-cultural dynamics).

Example: A Bulgarian manager in France noticed colleagues often over-clarified basic processes to him in meetings, even though he had a proven track record. Comments like “This might be new for you, so let me explain…” were meant to be helpful, but left him feeling patronized and alienated. Once recognized, these microaggressions were addressed through a diversity and inclusion initiative, dramatically improving the team’s cohesion and the manager’s sense of belonging.

By now, it’s clear that cross-cultural conflict is a multi-faceted challenge – part structural (differing norms), part psychological (biases and emotions). But here’s the good news: with awareness and the right strategies, these conflicts can be resolved and become opportunities for stronger teams. In the next section, we’ll move from diagnosis to action: concrete strategies for conflict resolution that business professionals can apply. We’ll incorporate classic models (like Thomas-Kilmann’s five conflict modes of avoiding, accommodating, competing, compromising, collaborating) and show how cultural and emotional intelligence produce the best outcomes together.

Strategies for Effective Cross-Cultural Conflict Resolution

Effectively resolving cross-cultural conflicts requires a blend of empathy, cultural intelligence, and tactical problem-solving. It’s not a one-size-fits-all situation – the best approach often blends multiple strategies. Below, we outline key strategies, each paired with actionable steps and examples illustrating how they play out in global businesses (with a nod to the pharmaceutical industry, where high-stakes, cross-border teamwork is common).

1. Build Cultural Awareness and Competence

Before conflicts even arise, education and awareness can lay a solid foundation. Cultural competence means understanding (at least at a basic level) the norms, values, and communication styles of your colleagues’ cultures.

- Invest in Training: Offer workshops or e-learning modules on cultural differences and inclusive teamwork. Include frameworks like Hofstede’s dimensions (for broad national culture traits) and Fons Trompenaars’ model or Erin Meyer’s Culture Map for more nuanced insights. For example, a team at a global pharmaceutical firm might take a short course on “Working Effectively Across [X and Y] Cultures” before a major project.

- Use Cultural Guides or Mentors: Create quick-reference guides for key dos and don’ts in various cultures (especially those represented in your team). Encourage mentorship where a team member from Culture A “buddies up” with one from Culture B to exchange cultural insights. This creates safe spaces for asking questions like “I noticed in meetings you do X; what does that mean in your culture?”

- Foster Open Dialogues: Normalize conversations about culture. Leaders can set the tone by sharing experiences (“When I first worked in Japan, I was surprised by…”). Include a segment in team meetings or onboarding where team members share a bit about their cultural background and working style. This both celebrates diversity and preempts misunderstandings.

Example: A global clinical trials team in a pharma company, including members from Bulgaria, Scandinavia, and Japan, held a “culture exchange” session. Bulgarian colleagues explained the importance of hierarchy and building personal rapport in their work style, while Scandinavian colleagues discussed their egalitarian approach, and Japanese colleagues emphasized consensus-building. The result? Team members reported fewer misunderstandings afterward and even devised a hybrid meeting style that combined these approaches. Essentially, they turned a potential source of conflict into a learning opportunity, increasing empathy across the board.

2. Establish Clear, Neutral Communication Norms

Communication is the first casualty in cross-cultural conflict. To prevent and resolve issues, teams should establish norms that prioritize clarity, respect, and active listening:

- Avoid Jargon and Idioms: What’s common lingo for you might be gibberish to someone else. Global teams should aim for plain language. Phrases like “let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater” could confuse colleagues who are non-native speakers or who take things literally. Instead, say, “let’s not discard the good ideas with the bad.”

- Use Multiple Channels: In virtual teams, pair verbal communication (meetings, calls) with written summaries. People process information differently; some might appreciate seeing key points in writing (and non-native speakers can double-check they understood correctly).

- Summarize and Confirm: Especially after a heated discussion or complex meeting, summarize the agreed points and next steps: “To confirm, we decided X by Friday and Y by next week, correct?” This gives everyone a chance to clarify any lingering confusion.

- Encourage Questions: Make it explicit that asking clarifying questions is welcome. Sometimes, cultural newcomers stay silent to avoid looking ignorant, but leaders can model that no question is dumb if it helps mutual understanding.

- Mind Your Tone and Pace: In written communication, a terse style might be efficient to you but can read as angry or rude to someone else. Add a friendly line (“Hope you’re well,” or “Thanks for the effort on this”) to soften emails if needed. When speaking, be mindful that if you speak very fast, slowing down a bit can help non-native speakers follow along.

Example: In a regulatory compliance meeting involving teams from Bulgaria and the USA, the American project manager noticed that idioms were causing blank stares. She consciously replaced colloquial language with simpler terms and summarized key decisions in bullet points on a shared screen. By the meeting’s end, she asked each site (Bulgaria and U.S.) to reiterate their understanding of next steps. The result was alignment and no follow-up emails saying “Wait, what are we doing?”, which had previously been an issue due to miscommunication.

3. Adapt Conflict Resolution Styles to the Culture

The Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI) identifies five approaches to conflict (competing, collaborating, compromising, avoiding, accommodating). Cultures often have preferences among these, which means a manager’s conflict resolution style should flex depending on who’s involved:

- Direct vs. Indirect Approach: Recall conflict-avoidant vs confrontational cultures. If mediating between an indirect communicator (say, from Japan or Bulgaria) and a direct one (say, from Germany or Israel), consider a blended approach. You might first allow each to express concerns in their preferred way (maybe one writes a memo – indirect, one speaks in a meeting – direct) and then bring them together once each perspective is clearly laid out.

- Individual vs. Group Resolution: In some cultures, it’s better to address an issue one-on-one first (to avoid embarrassing someone in front of others), whereas others might favor a team discussion so everyone is aligned. Gauge what the parties are comfortable with.

- Formality vs. Informality: Some cultures might appreciate a formal process (documents, official mediation meetings) for serious conflicts, lending a sense of due process, whereas others might find that overkill and prefer a coffee chat to sort things out. Tailor your approach to the expectations of those involved.

- Leverage Mediators: If you know someone on the team who shares cultural ground with a colleague in conflict, consider having them as a go-between if appropriate. However, ensure this person remains neutral and is respected by both parties.

Example: A German and a Bulgarian team clashed over project timelines. The German approach was to hold a joint meeting and air the grievances directly – “let’s get it all on the table.” The Bulgarian approach was to discuss issues in smaller circles first to avoid direct confrontation. The conflict leader decided to adapt: first, he had one-on-one chats with key Bulgarian team members to hear their concerns (private, indirect setting). Armed with that information, he then convened a group meeting where he framed the discussion around shared goals (more on that soon) and invited the German team to present facts and the Bulgarian team to share their perspective. This two-step approach – private, then public – honored both styles and helped diffuse tension. The Bulgarian team felt heard without the pressure of immediate confrontation, and the German squad appreciated the eventual open dialogue. Outcome: They realigned the timeline expectations without lingering resentment.

4. Focus on Shared Goals and “Big Picture” Outcomes

When conflict threatens to divide a team, zooming out to the larger goal can unite everyone. Reminding people of what’s at stake beyond the interpersonal friction can shift the mindset from “me vs. you” to “us vs. the problem”.

- Reiterate the Mission: Start conflict resolution discussions by clearly stating the common goal. For example: “We all want this product launch to be successful in both markets,” or “Our shared goal is getting this clinical trial approved on time to help patients.” This sets a collaborative tone.

- Highlight Interdependence: Emphasize how each party’s contribution is vital to success. If two departments clash (say marketing vs. R&D, a common dynamic), spell out: “Marketing needs R&D’s technical excellence, and R&D needs marketing’s customer insights. Neither can succeed alone on this project.”

- Visualize Success and Consequences: Paint a picture of what success looks like if they resolve the conflict (“If we merge our approaches, we could hit the market first and all get recognition”) versus the cost of ongoing conflict (“If we can’t resolve this, the launch gets delayed, competitors might overtake us, and all our work could be for nothing”). This isn’t to scare, but to create a unified urgency.

- Celebrate Common Ground: Even in conflict, there may be points of agreement. Identify and acknowledge them: “We both care deeply about quality,” or “We’re both under pressure to deliver – that’s something we share.”

Example: A multicultural pharma team was torn: should they prioritize cost efficiency (urged by the Bulgarian manufacturing lead) or speed to market (pushed by the American marketing director) for a new drug launch? The debate got heated, reflecting a deeper cultural nuance: Bulgaria’s context stressed careful resource use and long-term partnership trust, while quarterly results and first-mover advantage drove the U.S. side. The project manager intervened by reframing the conflict around a shared goal – patient impact. He reminded them that both cost control and speed were means to a larger end: “delivering an affordable, effective treatment to patients in need as soon as possible.” By discussing how a delay could literally cost lives or how overpriced medication could limit patient access, the team found a motivating common purpose. They then collaborated on a compromise: cut costs where possible without affecting timeline-critical tasks. The shift from departmental goals to organizational mission cooled the conflict and spurred a solution.

5. Create a Safe Space for Dialogue (Psychological Safety)

People resolve conflicts best when they feel safe to speak up without fear of ridicule or retribution. Psychological safety is that sense of confidence that the team environment is trusting, respectful, and a safe place for interpersonal risk-taking (a term popularized by Harvard’s Amy Edmondson). How to cultivate it:

- Set Team Norms Early: Right from project kickoff, agree on rules like “We attack problems, not people,” “Everyone will get a chance to speak,” and “Disagreements will be handled respectfully and offline if needed.” Put these in a team charter or a visible doc.

- Lead with Vulnerability: Leaders (formal or informal) should model that it’s okay to be human. Admitting a mistake (“I misunderstood that cultural cue, I’m sorry”) or expressing uncertainty (“I’m not sure how to approach this – what do you all think?”) can normalize not having all the answers and encourage others to voice concerns or ideas.

- Regular Check-ins: Don’t wait for conflicts to explode. Have short, frequent check-ins where people can share any budding concerns. This could be part of a weekly meeting (“Quick round: any concerns or cultural observations anyone wants to discuss?”) or through an anonymous channel (like a suggestion box or a quick survey).

- Active Listening Techniques: Encourage paraphrasing (“So what I hear you saying is…”) and clarifying questions in discussions. This shows that people are truly trying to understand each other. It also slows down potentially heated exchanges and ensures each side feels heard before the other responds.

Example: A Bulgarian software firm working with teams in India and the UK set up bi-weekly “team retrospectives” where any team member could raise an issue, including cultural frictions. They kicked it off by allowing an anonymous submission of topics, which a facilitator would then bring up. In one session, someone anonymously shared, “Sometimes I feel my accent makes people take me less seriously.” This led to an open discussion (the person later came forward voluntarily) and the team addressed it by agreeing to be more patient and attentive with all speakers, regardless of accent, and even instituted a no-interruption rule until someone finishes speaking. The safe environment of these regular dialogues prevented many small issues from festering. Over time, trust grew, and fewer issues were raised anonymously as people felt more comfortable speaking directly. In surveys, team members reported higher satisfaction and trust, aligning with research showing that employees who feel their managers create safe environments are far more likely to feel their perspectives matter.

6. Bring in Mediators or Cultural Brokers When Needed

If a conflict becomes especially tense or deadlocked, a neutral third party can make a big difference. This isn’t a failure; it’s recognizing that a mediator can navigate emotions and reframe more objectively.

- Internal Mediators: This could be an HR partner, a respected senior colleague, or someone from a diversity & inclusion team trained in conflict resolution. Ideally, someone who understands the cultures involved, or at least has high cultural intelligence.

- External Mediators: A professional mediator or cross-cultural consultant might be beneficial for major disputes (especially those involving external partners or clients). They bring structured techniques to guide discussions and are neutral (so neither party feels the other’s perspective is being favored).

- Peer “Cultural Broker”: Sometimes, a colleague who shares one party’s culture and is trusted by the other party can serve as a bridge. This person isn’t officially a mediator but can informally help each side interpret the other’s actions more charitably.

- Set Ground Rules: If mediation is needed, establish that the mediator’s role is not to judge who’s right but to facilitate understanding and agreement. Both parties should agree to listen fully when the other speaks (mediators often use a format where each side speaks without interruption, and then the mediator paraphrases to ensure understanding before moving on).

Example: A Bulgarian pharma supplier and a French client were at loggerheads over missed deadlines and quality expectations. Emails were turning icy. They brought in a mediator who was **bilingual and familiar with both French and Bulgarian business norms】. In separate pre-meetings, the mediator learned that the Bulgarian side felt the French kept changing specs (hence delays), while the French side thought the Bulgarian timelines were unrealistic from the start. In the joint session, the mediator helped translate both language and intent. When the French manager said, “We need guarantees,” the mediator reframed it as, “They need to feel confident in our plan going forward; can we show them our risk mitigation?” The mediator’s cultural lens caught that “guarantees” to a Bulgarian sounded like blame, but to the French, it was about assurance. By clarifying this, the Bulgarian team didn’t get defensive and instead provided a revised plan. The conflict moved from finger-pointing to problem-solving, resulting in a new agreement on deliverables.

7. Invest in Long-Term Relationship Building

Finally, remember that conflict resolution isn’t just a one-off tactic, but part of building a cohesive, inclusive team culture. Teams that play the long game by strengthening relationships will handle new conflicts more gracefully.

- Cultural Immersion and Exchange: Encourage team members to experience each other’s culture. If budgets allow, host offsites or team meetings in each other’s countries. If not, do virtual cultural tours or celebrate cultural holidays. One company did a “culture swap” lunch-and-learn: one week, the Indian team taught basic Hindi phrases and explained Diwali, and another week, the Brazilian team taught some Portuguese slang and discussed Carnival.

- Informal Socializing: In virtual teams, it could be as simple as a monthly virtual coffee chat or online game night. In co-located teams, after-work gatherings, team lunches, or group volunteer activities can humanize colleagues beyond work roles. Personal connections often translate to more patience and generosity during conflicts – it’s harder to stay mad at “Ahmed from Cairo, who you know loves hiking and has three kids” than at “that overseas colleague delaying my project.”

- Mentorship and Buddy Systems: Pair new international hires with a buddy who can help them integrate and understand the company’s unspoken cultural norms. This pre-empts conflicts born out of sheer ignorance.

- Celebrate Wins and Learn Together: When a team overcomes a cultural challenge or conflict, acknowledge it. “Remember when we struggled with time zones and nearly missed that deadline? Now we’ve got a great system for it – awesome work adapting, team!” This reinforces the idea that working through differences makes the team stronger. Also, consider sharing articles or books (maybe even starting a mini book club) on cultural intelligence to keep learning as a group.

Example: A multinational consulting firm noticed frequent minor tensions in their globally distributed project teams. They instituted an annual “Cultural Exchange Week.” Each office (or region) would host a day of activities – one day might be “Malaysia Day” with a virtual tour of Kuala Lumpur and Malaysian team members sharing local proverbs about teamwork; another might be “Nordic Day” highlighting Scandinavian meeting etiquette and a friendly quiz about famous Danish companies. One tangible change after these exchanges: a European team started scheduling critical meetings not only avoiding lunchtime in Europe but also being mindful of prayer times in their Middle Eastern colleagues’ region – a sign of more profound mutual respect gained. Over the years, they reported a drop in escalated conflicts, attributing it to colleagues’ better understanding of each other’s contexts. Essentially, they proactively built empathy reservoirs that paid off when conflicts loomed.

Equipped with these strategies, let’s consider why it’s worth the effort. Spoiler: resolving cross-cultural conflicts is not just a feel-good HR exercise; it’s directly linked to team performance, innovation, and even the bottom line. Next, we’ll highlight the benefits organizations reap when they master cross-cultural conflict resolution, supported by recent studies and statistics.

Benefits of Resolving Cross-Cultural Conflicts Effectively

Resolving cross-cultural conflicts isn’t just about harmony—it’s a key driver of team performance. Inclusive teams are 35% more productive, and diverse ones make better decisions 87% of the time. Here’s how proactive conflict resolution unlocks that value.

Improved Team Collaboration and Cohesion

Constructively managed conflicts foster trust and understanding, helping teams unite and function cohesively.

- Unity and Trust: Once cleared, misunderstandings often reveal common goals and build stronger bonds, like a crew weathering a storm together.

- Efficiency: With trust restored, team members share more openly and collaborate.

Example: A global R&D team from Bulgaria and Switzerland overcame tension over data sharing by standardizing processes. Communication improved, and they beat their following timeline by 20%.

Increased Innovation and Creativity

Diverse perspectives create sparks if teams are safe to clash and collaborate.

- Idea Synergy: Conflicts often arise from different viewpoints. Once reconciled, those perspectives can fuel novel solutions.

- Psychological Safety: Post-conflict environments often enable bolder, more creative thinking.

Example: A Bulgarian and American team resolved a dispute over experimental methods. Their compromise led to an oncology research breakthrough neither side would’ve reached alone.

Higher Employee Engagement and Retention

When employees see their views respected and conflicts addressed fairly, morale and loyalty improve.

- Belonging Drives Retention: People stay where they feel heard and valued.

- Reduced Stress: Less tension means better focus and job satisfaction.

- Attractive Culture: Respectful, inclusive workplaces draw top talent.

Example: A Bulgarian company reduced foreign hire turnover by offering cultural training and conflict resolution support. One new hire praised how a clash turned into closer teamwork, saying: “I feel heard here.”

Faster Decision-Making and Project Delivery

Though conflict resolution takes effort, it prevents deeper delays down the line.

- Smoother Processes: Resolved tensions lead to more transparent communication and fewer bottlenecks.

- Quicker Meetings: Trust boosts speed in decision-making.

Example: A dispute between Bulgarian manufacturing and French distribution delayed a drug filing. Mediation realigned priorities, and the project hit its deadline, avoiding costly setbacks.

Strengthened Global Reputation and Client Relationships

Handling internal diversity well boosts credibility externally.

- Trusted Partner: Clients prefer teams that navigate cultural nuance smoothly.

- Negotiation Edge: Cultural fluency leads to better deals.

- Employer Branding: Inclusive environments attract global talent.

Example: A Bulgarian pharma exporter became known for bridging cultural gaps across EU stakeholders. This reputation helped them secure major contracts.

Alignment with Business Goals and Agility

Less internal friction means faster alignment and response to change.

- Clear Focus: Resolved teams spend more time innovating and executing, not managing drama.

- Faster Pivots: Cultural alignment makes it easier to adapt to evolving strategies.

Example: A vaccine development team aligned early on risk management preferences. They pivoted quickly when a new variant hit, launching ahead of slower competitors.

Positive Culture and DEI Excellence

Cross-cultural conflict resolution supports broader Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) goals.

- Trust & Respect: Fair processes build team-wide confidence.

- Cultural Intelligence: Each resolved conflict deepens mutual learning.

- Workplace Wellbeing: Reducing microaggressions and bias improves happiness and retention.

Example: A tech firm with five global offices addressed cultural friction early and celebrated different holidays. Job satisfaction soared, with 84% of employees feeling valued by leadership.

Cost Savings and Risk Mitigation

Unresolved conflict is expensive, slowing teams, driving turnover, and inviting legal trouble.

- Efficiency Gains: Conflict resolution often uncovers and fixes hidden inefficiencies.

- Lower Turnover: Inclusive teams retain talent, saving rehiring costs.

- Legal Risk Reduction: Respectful cultures avoid issues escalating into disputes.

Example: A Euro-Asian joint venture nearly collapsed due to cultural misunderstandings. Mediation salvaged the deal, saving legal costs and millions in investment. Another firm prevented a six-month product delay, saving significant revenue, by intervening early.

Real-World Examples of Cross-Cultural Conflict Resolution

To ground our discussion, let’s examine some real-world scenarios where cross-cultural conflicts arose and were resolved. These examples illustrate common friction points and how the strategies we’ve discussed come into play, often turning conflict into a learning experience and even a strategic advantage.

Example 1: Miscommunication in Performance Feedback

Scenario: A Bulgarian manager in a Swiss biotech firm struggled with a British colleague over giving feedback. The Bulgarians preferred indirect feedback to maintain team harmony (a high-context communication approach). For instance, instead of saying “Your report needs major changes,” he might say “Perhaps we could refine this section a bit if we have time.” Coming from a low-context culture, the British colleague found this feedback style unclear and not urgent enough, resulting in delayed corrections on a critical regulatory document.

Conflict: The Brit felt frustrated (“Why won’t he just tell me plainly what’s wrong?!”), and the Bulgarian felt awkward (“I’m trying to be polite, why isn’t he getting it?”). Due to this communication gap, deadlines were being missed.

Resolution: The company held a cultural communication workshop where both learned about each other’s styles. The Bulgarian manager discovered he could be slightly more direct without being rude, using phrases like “To be clear…” or “It’s important that…” to signal importance. The British colleague learned to recognize and ask for clarity when feedback seemed too soft (“Just to confirm, is the main issue X?”). They agreed on a blended feedback process: the Bulgarian would provide written notes with explicit points (helpful for the Brit), and the Brit would be patient with less direct phrasing in verbal chat, seeking clarification as needed.

Outcome: They created a standardized feedback template balancing both styles – bullet points (direct) but couched in polite language (indirect). The British colleague got the clarity needed; the Bulgarian manager felt he could still be respectful. Subsequent documents were submitted on time with quality improvements. Observation: This example underscores that mutual adaptation, rather than one side “winning,” solved the miscommunication. Both expanded their communication repertoire – a win for their personal development.

Example 2: Hierarchy vs. Consensus in Decision-Making

Scenario: A Bulgarian supply chain manager posted in Denmark felt frustrated in meetings. Used to a hierarchical process, she expected clear decisions from leadership. But the Danish team operated with flat structure and consensus – even minor decisions involved group discussion and input from various levels.

Conflict: The Bulgarian manager privately thought, “We’re wasting time; why won’t the boss just decide? Are they indecisive?” Meanwhile, some Danish colleagues felt the Bulgarian was too impatient and authoritarian, always wanting to “just decide already” instead of valuing everyone’s input. The friction slowed down a project to streamline inventory, ironically causing delays in a project meant to increase efficiency.

Resolution: Recognizing the cultural clash, leadership implemented a hybrid decision framework. For routine issues (where broad input was valuable and time was less critical), they went with the Danish style – lots of collaboration and discussion. But for time-sensitive decisions (like fixing an urgent supply bottleneck), they agreed the Bulgarian manager could take charge more directly, and others would defer to that hierarchy for speed. They communicated this plan to the whole team so everyone understood when each approach would be used.

Outcome: Efficiency improved. The Bulgarian manager felt respected (her need for structure was validated in critical moments) and learned to be more patient in non-urgent discussions. Danish team members realized that some structure could be beneficial and weren’t caught off guard when occasionally told, “We’ll handle this top-down due to urgency.” The project finished on time. Observation: This case shows cultural compromises – they didn’t fully abandon either culture’s method, but allocated each to where it fit best. It’s also a reminder that learning from a different style can broaden a manager’s toolkit: the Bulgarian manager likely became more comfortable with consensus-building (useful even beyond Denmark), and the Danes saw that a bit of hierarchy at times isn’t evil if used judiciously.

Example 3: Different Attitudes Toward Risk

Scenario: In a global R&D team for a new medical device, Bulgarian researchers and American product leads disagreed on how much testing was enough. The Bulgarians were risk-averse, pushing for extensive validation to avoid any regulatory or safety issues (reflecting high uncertainty avoidance, common in many cultures, including Bulgaria). The Americans, under competitive pressure, wanted to fast-track some tests, comfortable with a bit more risk to hit the market sooner (a more risk-tolerant approach).

Conflict: Each side saw the other as “extreme”: the Americans thought the Bulgarians were over-cautious and slowing progress, potentially letting competitors win. The Bulgarians thought the Americans were reckless, potentially endangering the project or patients by cutting corners. Meetings grew tense, with neither side willing to budge, and it became a deadlock stalling the project.

Resolution: They brought in a third-party mediator with cross-cultural expertise. Importantly, the mediator helped each side articulate WHY they held their view, culturally and practically. The Americans shared the market context – if they’re late, no one benefits from the safer device because it’ll be irrelevant. The Bulgarians shared historical examples of projects that failed due to one missed test, emphasizing how, in their experience, “slow is smooth, smooth is fast” in the long run. Understanding each other’s fears and drivers softened the stances. They compromised: the plan included additional checkpoints (to satisfy the Bulgarians’ caution) but also parallel processing of some tests and paperwork to save time (to appease the Americans’ need for speed).

Outcome: They did not experience any major regulatory hiccups or rework, thanks to the extra safeguards, and still managed to launch only slightly later than the Americans’ ideal date. Both sides acknowledged that the final approach was better than either original plan alone. Observation: This illustrates how mediation and reframing the conflict (from “conservative vs. aggressive” to “how do we both ensure safety AND timeliness”) can find a creative middle path. It also highlights a cultural point: attitudes towards risk can be culturally influenced, and balancing them can strengthen a project (one side prevents foolish risks, the other prevents paralysis by analysis).

Example 4: Virtual Team – Time Zone and Priority Conflicts

Scenario: A virtual team for a software project included members from India, Germany, the UK, and Bulgaria (managed by a Bulgarian in the U.S.). They clashed over scheduling and priorities. The Indian team needed flexibility (they often had local holidays or infrastructure hiccups), sometimes asking for deadline extensions. The German team insisted on fixed schedules and firm deadlines (sound familiar?), considering flexibility endangering reliability. The UK team tried to mediate, preferring a balanced approach, but ended up pleasing neither fully.

Conflict: Remote collaboration challenges amplify cultural ones. Emails started flying with CCs to managers complaining about “the other team’s” lack of cooperation. The Indian side felt unfairly criticized for circumstances often beyond their control (e.g., “Power outage due to a storm isn’t because we’re lazy!”). The German side felt others weren’t taking commitments seriously, which offended their sense of professionalism (“If we said Friday, it means Friday.”).

Resolution: The Bulgarian coordinator realized this was more than a scheduling issue – it was cultural. He organized cross-cultural workshops via video call. Each team took turns presenting their work culture and constraints: Indians explained how they buffer timelines due to known local infrastructure issues and value adaptability; Germans explained how any deviation can cascade into breaches of client trust in their context; the UK folks explained how they try to weigh both client expectations and team well-being. This humanized everyone (“Oh, they’re not just being difficult – they have reasons.”). With understanding improved, the coordinator then proposed a schedule with built-in buffers. Essentially, set deadlines earlier internally than promised to clients, allowing wiggle room for the Indian team, which made the Germans more comfortable. They also staggered work so critical path tasks weren’t all on one team.

Outcome: The project flow improved. Deliverables stopped being late to the client, and internally, the teams had fewer flare-ups. The simple act of acknowledging each team’s reality diffused a lot of tension. Observation: Virtual teams often suffer from the “distance makes it easier to assume the worst” problem. By face-to-face (even if virtual) cultural sharing, this example shows the power of empathetic understanding and structural adjustment. Also, it highlights the value of a leader who can act as a cultural integrator – the Bulgarian coordinator in a US company, balancing between multiple cultures, played that role well.

Example 5: Addressing Microaggressions and Bias

Scenario: A Bulgarian quality assurance (QA) manager joined a French pharmaceutical firm. He started noticing subtle slights: colleagues would always explain things to him in excruciating detail (more than to others), as if assuming he wasn’t up to speed. Occasionally, he’d hear a quip like “Well, Eastern Europe doesn’t exactly have Big Pharma, so let’s show you how we do it here.” These microaggressions made him feel underestimated and frustrated.

Conflict: This wasn’t an open conflict but a cold one. The manager felt disrespected, but due to his cultural upbringing, he was hesitant to confront or report it; he feared rocking the boat or being labeled overly sensitive. Meanwhile, the French colleagues (and other nationalities in the office) were largely oblivious to the impact of their actions, likely thinking they were being helpful or just joking.

Resolution: To the company’s credit, they had been rolling out a larger DEI initiative that included cultural sensitivity training. The training covered recognizing unconscious bias and the harm of stereotypes. It’s likely that in those sessions, examples similar to what the Bulgarian manager faced were discussed (maybe even raised by him or an ally). Post-training, colleagues realized, for instance, that over-explaining or making “East vs West” comments were not okay. Additionally, the manager gained confidence from the inclusive messaging and saw that management had his back. He started to speak up gently when a microaggression occurred, like, “Thanks, I actually have quite a bit of experience with this, but I’ll ask if I need help,” to signal he’s on equal footing.

Outcome: Over a few months, the workplace climate improved. The microaggressions dwindled as awareness rose. The manager reported feeling more valued and recognized for his expertise, eventually leading a major project successfully. Observation: This case highlights that not all conflicts are loud; some are quiet battles of morale. It reinforces the importance of DEI programs in surfacing and addressing unconscious bias. It also shows that empowerment (through organizational support) can enable those feeling marginalized to assert themselves constructively.

Takeaways from the Examples:

These scenarios share common lessons, especially for business professionals and leaders:

- Cultural Adaptability is a Two-Way Street: It’s powerful when all parties flex a little. In each example, notice that resolution came from mutual adaptation or third-party intervention, not one side dominating.

- Clarity and Empathy Trump Assumptions: Most conflicts ease when folks actually listen to the other’s perspective (often facilitated by a mediator, workshop, or deliberate conversation). It sounds obvious, but amid work stress, it’s often missed.

- Structure Helps: Whether it’s a hybrid decision framework, a feedback template, or a new communication rule, giving a process for handling differences helps remove personal emotion from the equation.

- Leaders as Bridge-Builders: The role of the Bulgarian coordinator (Ex. 4) or the proactive project manager (Ex. 3) shows how leaders who understand cultural variances can preempt or solve conflicts by explaining contexts and encouraging empathy.

- Conflict to Collaboration: When resolved, the very issue that caused conflict often became a source of strength (e.g., the hybrid approach in R&D, or the faster timelines with built-in buffers). This aligns with the idea that in diverse teams, conflict managed well can lead to more robust solutions than homogenous teams might develop.

Having dissected these examples, it’s evident that cross-cultural conflict resolution is both an art and a science, requiring sensitivity, knowledge, and skill. Above all, it requires a mindset that sees diversity as an asset, not a hurdle. Let’s conclude with a forward-looking perspective: How can organizations embed these lessons into their DNA, and why is mastering cross-cultural conflict resolution absolutely pivotal for modern businesses committed to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and outstanding team performance?

Turning Cross-Cultural Challenges into Opportunities

In a world where work teams span continents and cultures, cross-cultural conflicts are inevitable – but they’re also launchpads for growth. Forward-thinking organizations view these moments not as crises, but as opportunities to innovate, strengthen their culture, and gain a competitive edge.

When confronted with a cultural clash, ask “How do we fix this?” and “What can we learn and improve from this?” This mindset shift transforms the narrative:

- A misunderstanding becomes a chance to improve communication systems.

- A clash of working styles becomes an impetus to create better processes.

- A moment of offense or bias catalyzes DEI initiatives that make the workplace better for all.

Key Takeaways to Embrace

- Cultural Awareness is Non-Negotiable: It’s the first step in turning conflict into collaboration. Regular training, storytelling, and knowledge exchange about cultural differences equip teams with empathy. It’s much easier to resolve a dispute (or avoid it) when team members can pause and think, “Oh, this might be because in their culture, X is viewed differently. Let me check rather than assume.” Consider building cultural awareness goals into your leadership KPIs or team development plans.

- Adaptability Over Uniformity: One-size-fits-all management doesn’t cut it in global teams. The best leaders are cultural chameleons – they adapt their style to meet the team’s needs. This doesn’t mean losing authenticity; it means expanding your range. For instance, become comfortable both with Americans’ directness and East Asians’ indirectness, switching gears as needed. Thomas-Kilmann conflict modes remind us that sometimes you need to collaborate, other times compromise, occasionally accommodate – having all those tools is vital.

- Technology as an Ally: In virtual multicultural teams, leverage tools thoughtfully. Use video calls for richer communication when possible (seeing faces can prevent misinterpretation of tone). Use project management software to ensure everyone sees the same “source of truth” for deadlines (reducing ambiguity). Even simple things like timezone scheduling tools show respect for everyone’s local time.

- Lead by Example in DEI: Connect the dots explicitly between cross-cultural competence and the company’s DEI values and business outcomes. Leaders should talk about it: “Our inclusive culture is why we’re able to launch products faster,” or “Handling that conflict well not only saved the project, it showed what our values mean in action.” This reinforces that these efforts are core to the business, not side projects. Moreover, it underlines a modern ethos: diversity is a fact, inclusion is an act, and conflict resolution is part of that action.

- Continual Learning: Cultures evolve, and so do teams. Keep the learning loop open. After a conflict resolution, debrief as a team (in a blameless way): What did we learn about X culture? How might we do things differently going forward? Encourage curiosity – maybe someone shares an article about a tradition they knew that could be insightful. Organizations can provide resources (books like Erin Meyer’s “The Culture Map”, or internal wikis on cultural tips) to sustain this learning.

Forward-Looking Conclusion

Mastering cross-cultural conflict resolution is more than solving workplace tiffs – it’s about building the future-ready, innovative, and inclusive teams that define organizational success in the 21st century. As businesses increasingly operate on a global stage, those that can bridge cultural gaps swiftly and respectfully will outperform those that get entangled in them. They’ll unlock the full creative and productive power of their diverse workforce. They’ll attract top talent from around the world who know this is a place where their unique background is celebrated, not just tolerated.

In essence, every cross-cultural conflict carries the seed of a breakthrough. By applying the strategies discussed – from sharpening cultural awareness to crafting clear communication norms and fostering psychological safety – professionals can turn potential flashpoints into moments of insight and innovation. And by aligning these efforts with broader DEI and team performance goals, organizations ensure that diversity truly becomes their strength.

As you finish this article and step back into your role, consider this challenge: What’s one thing you can do this week to improve cross-cultural understanding on your team? It could be as simple as striking up a conversation with a colleague about their work style preferences or proposing a team discussion on cultural norms. Such small acts, accumulated, create a workplace where differences are bridges, not barriers.

In the words of a wise leader, “Diversity is being invited to the party; inclusion is being asked to dance.” We’d add: Conflict resolution is learning to dance gracefully when someone inevitably steps on someone else’s toes – and even turning it into part of the dance. By doing so, we don’t just avoid falling over – we create something beautiful and collaborative that no solo dancer could achieve.

Deepening Your Understanding of Cross-Cultural Conflict Resolution

Cross-cultural competence is not a one-time effort but an ongoing journey of learning, adapting, and refining skills. In today’s globalized workplace, especially in pharmaceutical industries, understanding and managing cultural differences is essential for building solid teams, fostering innovation, and achieving organizational success. By engaging with insightful books, articles, and resources, you can further develop your ability to navigate cultural nuances and lead with empathy and effectiveness.

The Culture Map by Erin Meyer is a must-read for a comprehensive understanding of cross-cultural dynamics. It delves into how cultural differences influence communication, leadership, and collaboration, providing actionable insights for global teams. For a more practical approach, Kiss, Bow, or Shake Hands by Terri Morrison and Wayne A. Conaway offers a hands-on guide to cultural norms in over 60 countries. Richard D. Lewis’s When Cultures Collide further explores how cultural differences impact leadership and team performance, with detailed case studies to contextualize the theory.

On the theoretical side, Daniel J. Boorstin’s The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-events in America provides a unique perspective on how perceptions shape behavior, an essential consideration in cross-cultural conflict resolution. To supplement your learning with real-world applications, the article Navigating Feedback Across Cultures: A Guide for Foreign Managers in Bulgaria offers excellent insights into managing cultural nuances in Bulgaria, making it an essential read for managers working in the region.

To stay updated on cultural intelligence, Harvard Business Review’s articles on cross-cultural leadership and emotional intelligence provide concise yet impactful guidance. For those who prefer structured learning, online courses like Coursera’s Intercultural Management by ESCP Business School or LinkedIn Learning’s Managing Cross-Cultural Teams offer practical tools for managing diverse teams effectively.