At a glance, facts & figures

The long‑planned Deve Bair railway tunnel would finally stitch together Bulgaria’s line to Gyueshevo with North Macedonia’s line via Kriva Palanka, completing the Sofia–Skopje railway on Pan‑European Corridor VIII. The tunnel is ~2.35–2.37 km long; parts were started in the 1940s but never finished.

- Tunnel name: Deve Bair (border Bulgaria–North Macedonia)

- Length: ~2.35 km (current design); ~2.37 km WWII plan; ~1.15 km NM / ~1.20 km BG (design split)

- First rail to border: Kyustendil–Gyueshevo opened 16 Jul 1910; Radomir–Kyustendil opened 26 Jul 1909

- WWII works: BG drove ~1,194 m and lined ~550 m before Aug 1944 halt

- On the North Macedonian side, Phase I (Kumanovo–Beljakovce) reopened in Dec 2024/Jan 2025; Phase II (Beljakovce–Kriva Palanka) is under construction; Phase III (Kriva Palanka–border, incl. tunnel) has new EU‑funded environmental docs and an active procurement track.

- On the Bulgarian side, the last ~2.4 km from Gyueshevo to the border was put out to tender in July 2025, while a parallel project modernises the Radomir–Gyueshevo section.

- In July 2025, the EU and both governments reaffirmed plans to finalise the intergovernmental tunnel agreement and set up joint working groups to move it from paper to excavation.

Where exactly is the tunnel, and why does it matter?

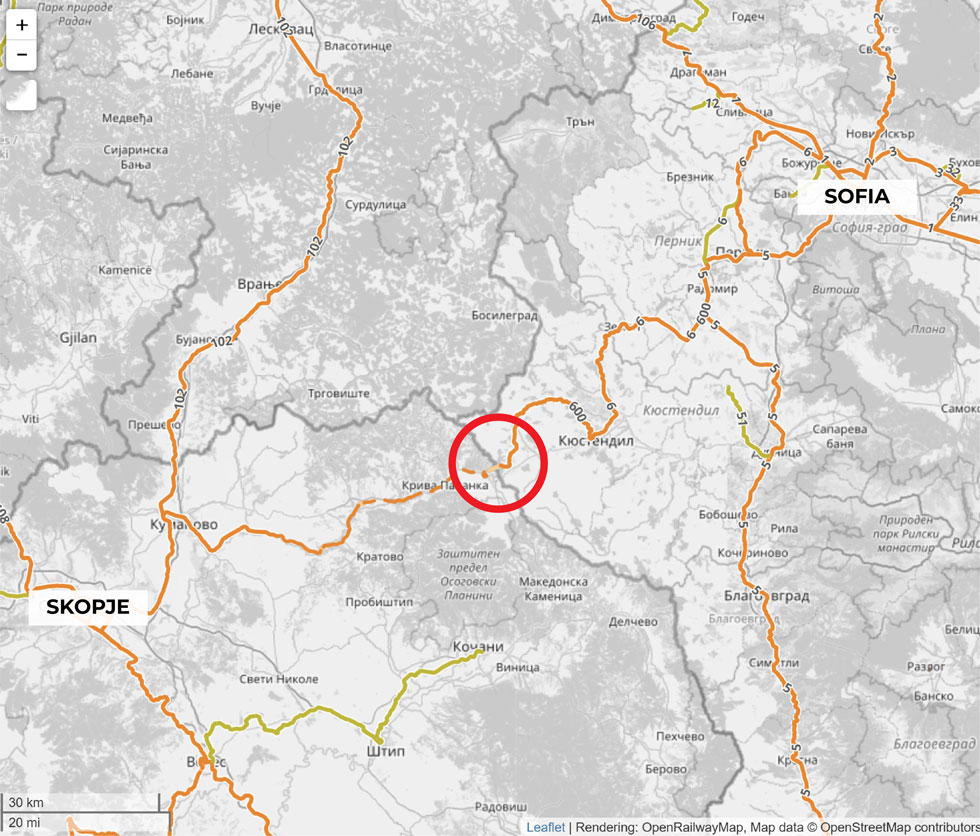

The Deve Bair tunnel will run under the Deve Bair pass (∼1,160 m a.s.l.) between Gyueshevo (BG) and Kriva Palanka (NM), closing the last gap on the east–west Corridor VIII rail route from the Adriatic (Durrës) to Bulgaria’s Black Sea ports. The current design length is about 2,350 m (≈1,150 m on the North Macedonian side and ≈1,200 m on the Bulgarian side), reflecting modern surveys and safety standards.

A historical twist: in the 1940s, workers actually began the “watershed” tunnel. On Bulgaria’s side they drove ~1,194 m and fully lined ~550 m of a planned 2,368 m bore, work that ceased in August 1944. Different design baselines explain the small difference between the 2,350 m (today) and 2,368 m (WWII‑era plan) figures.

The long road to a short tunnel: a precise chronology

1878-1903 – From Berlin to blueprints

After the Berlin Treaty, Bulgaria’s governments repeatedly explored a western outlet across Ottoman Macedonia. Projects and diplomacy under Stambolov, Stoilov, and successors set priorities for a Sofia–Kyustendil–(Gyueshevo)–Kumanovo/Skopje link, but geopolitics kept plans on paper.

1905-1910 – Building to the border

- In 1905, the Radomir–Kyustendil–Gyueshevo contract was awarded to “Ivan P. Zlatin & Co.” to deliver a demanding mountain line featuring 14 large bridges and 18 tunnels.

- 26 Jul 1909: Radomir–Kyustendil opens amid a ceremony (PM Alexander Malinov in attendance). 16 Jul 1910: Kyustendil–Gyueshevo opens—pushing Bulgaria’s railway to the then‑Ottoman border. Gyueshevo station sits at 944 m, the highest normal‑gauge station on the Bulgarian network.

1912-1913 – Wars pause the dream

The Balkan Wars and shifting borders shelved the cross‑border link.

1941-1944 – The tunnel starts, then stops

- 3 May 1941: Bulgaria orders construction of Gyueshevo–Kriva Palanka–Kumanovo, including the Deve Bair tunnel.

- Work proceeds fast until Aug 1944, when it stops. The unfinished tunnel becomes a concrete reminder of a route that almost was.

Late 1940s-1980s – Cold War frost

Brief post‑war activity gave way to a chill after the Tito–Cominform split (1948). The border railway—and its tunnel—remained a strategic mirage.

1994-1997 – Corridor VIII is born

Europe’s Pan‑European Transport Corridors formally define Corridor VIII at Crete (1994) and consolidate it at Helsinki (1997), putting the Sofia–Skopje railway back on long‑term agendas.

1994-2004 – North Macedonia starts eastward

The Kumanovo–Beljakovce section remained operational until 1994; between 1994–2004 the government designed and partially built works towards Kriva Palanka, then stopped for lack of funds. EBRD

2011-2014 – Studies and relaunch

- 19 Jul 2011: Skopje selects the “Reference” alignment for the Eastern Section (Kumanovo–Deve Bair).

- 2014: Phase I rehabilitation starts on Kumanovo–Beljakovce with EBRD financing and international supervision.

2023-2025 – Momentum returns

- 2023: New ESIA prepared for Phase III (Kriva Palanka–border), detailing a single‑track mountain line with heavy tunnelling (including the border bore). European Investment Bank

- Dec 2024/Jan 2025: Phase I (Kumanovo–Beljakovce) completed and reopened to traffic. Phase II to Kriva Palanka is under active construction.

- Mar–Jul 2025: EU and both governments reaffirm commitments; working groups are created to finalise the cross‑border tunnel agreement.

- Jul 28, 2025: Bulgaria launches a tender for the remaining ~2.4 km from Gyueshevo to the border; in parallel, Pernik–Radomir modernisation tenders are issued (part of the broader Radomir–Gyueshevo upgrade).

What exactly will be built (and rebuilt)?

- North Macedonia (Phase III: Kriva Palanka → border, ~23.4 km): a new single‑track mountain railway with ~22 tunnels (≈9 km total) and dozens of bridges/viaducts; it reuses and completes the historical border tunnel on the Macedonian side. Design speed is 100 km/h.

- Bulgaria (Gyueshevo → border, ~2.4–2.5 km): a short new build completing the domestic network to the tunnel portal, alongside staged modernisation Radomir–Gyueshevo (ERTMS ready) under the Transport Connectivity Programme 2021–2027.

Travel‑time clues: The 2012 ESIA anticipated Skopje→Deve Bair in ~60 minutes on the reference alignment; Bulgaria’s ongoing upgrades target higher speeds east of the pass. Exact Sofia–Skopje journey times will depend on final signalling, speeds and stops, but the data point shows the route is planned for modern, hourly‑scale cross‑border operations rather than an all‑day slog.

Names, figures, and places

- The mountain pass: Deve Bair is a Turkish toponym often glossed as “Camel’s Hill/Slope” (deve = camel; bayır = hillside). It’s also the main road border crossing between Kriva Palanka and Gyueshevo.

- Gyueshevo station (1910): highest normal‑gauge station in Bulgaria’s network (944 m a.s.l.), terminus of the 34‑km Kyustendil–Gyueshevo branch with 8 tunnels (total ~950 m).

- The 1905 builders: “Ivan P. Zlatin & Co.” won the borderward contract; the line was an international effort—British rails, German steel bridges, Austro‑Hungarian explosives, Serbian oak sleepers, and multinational crews.

- The WWII start: Bulgaria’s 3 May 1941 decree triggered full‑scale works west of Gyueshevo; by Aug 1944, the tunnel was half‑driven from the Bulgarian side and partly lined—then history intruded.

- Corridor VIII DNA: a line that literally connects the Adriatic to the Black Sea, singled out at Crete (1994) and Helsinki (1997); today it’s backed by the EU, EBRD, EIB and WBIF.

The modern financing & institutional cast

- North Macedonia:

- Phase I (Kumanovo–Beljakovce, ~30.8 km) – rehabilitation complete; now in service.

- Phase II (Beljakovce–Kriva Palanka, ~34 km) – new build; construction ongoing with EBRD/EIB/WBIF support and international engineering supervision.

- Phase III (Kriva Palanka–border, ~23.4 km) – ESIA NTS completed in 2023; tendering for design & construction details 22 tunnels and 50+ bridges.

- Bulgaria:

- Gyueshevo–border (~2.4 km) – tender announced 28 July 2025; separate tender launched for Pernik–Radomir (17 km) as part of the Sofia–Radomir–Gyueshevo corridor upgrades.

- Radomir–Gyueshevo modernisation (ERTMS L1) – prepared under Transport Connectivity Programme 2021–2027 and EU rail‑interoperability planning.

- EU political push: In July 2025, the European Commission convened both countries; they reaffirmed Corridor VIII and agreed to finalise the intergovernmental tunnel agreement by working groups.

Traveller’s angle: what this line unlocks

- A one‑seat ride between two capitals. Once the tunnel and approaches open, Sofia ↔ Skopje becomes a straightforward intercity rail link instead of a patchwork of buses and border queues.

- A trans‑Balkan rail spine. Corridor VIII—Durrës–Tirana–Skopje–Sofia–Varna/Burgas—becomes a realistic rail itinerary, not just a map line.

- A route with stories built into the rock. From the 1909–1910 push to the border to the 1940s unfinished tunnel portals still visible near Gyueshevo, this is railway archaeology you can still stand next to—soon to be reanimated for modern trains.

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

Was there ever a train between the two countries?

No. Bulgaria reached Gyueshevo in 1910, and North Macedonia (and earlier Yugoslavia) built and operated Kumanovo–Beljakovce (closed 1994; now rehabilitated), but the border section and tunnel were never completed.

Why did work start in the 1940s—and stop?

Bulgaria ordered the Gyueshevo–Kriva Palanka–Kumanovo railway in May 1941. By Aug 1944 the tunnel was half‑excavated from the Bulgarian side; WWII’s end and subsequent politics froze the project.

Who is paying today?

A mix of EU instruments (WBIF/IPA/Global Gateway), EBRD and EIB loans and grants are underpinning North Macedonia’s phases, while Bulgaria’s short border link and upstream modernisation are in its Transport Connectivity Programme 2021–2027.

How hard is the engineering?

Very. The Kriva Palanka–border section alone needs ~22 tunnels (≈9 km) and scores of bridges/viaducts, plus reconstruction of the border tunnel itself.