The Beginning

During the mid-1960s at the height of the Cold War, Bulgaria – a Soviet-aligned Eastern Bloc nation – embarked on a surprising joint venture with France’s Renault to produce cars. This was unusual given the East-West divide, but the Bulgarian communist leadership was eager to industrialize and “project an image of a prosperous country with its automotive industry” (Periodismodelmotor). At the time, domestic car production was seen as a prestige project that could showcase socialist Bulgaria’s modernization. Bulgaria had no indigenous car design, so partnering with a Western automaker was a shortcut to acquire modern technology.

Why Renault? Bulgaria explored offers from several Western firms (Renault, Fiat, Simca, Alfa Romeo), ultimately finding Renault’s proposal most attractive. France under de Gaulle was relatively open to East-West trade, and Renault was willing to export complete knock-down kits for local assembly. On the Bulgarian side, an export-import company called ETO “Bulet” and the state industrial group “Metalhim” collaborated to make the deal possible. Bulet was a foreign trade organization holding hard-currency reserves (crucial for buying kits in Western markets). Metalhim was a state-owned defense manufacturer that could provide factory space and engineering manpower. In July 1966, the Bulgarian Council of Ministers formally authorized negotiations with Renault, leading to a contract signed on August 20, 1966. This created the “Bulgarrenault” joint venture (often branded as “Bulgar Renault”).

Key players in Bulgaria included:

- Gen. Georgi Yamakov (sometimes spelled Yamukov) – Director of Metalhim and the chief Bulgarian architect of the project. A trained engineer and army officer, Yamakov championed the auto venture and oversaw the development of a Bulgarian prototype car later (the Hebros 1100). He coordinated the factory setup in Plovdiv and liaised with French partners.

- Emil Razlogov, Director of ETO Bulet, handled the commercial negotiations with Renault. Razlogov’s organization provided the funding (in hard currency) to import car kits and equipment.

- Stefan Vaptsarov – Appointed technical director of the Bulgarrenault plant. He led the Bulgarian engineering team on the ground. In 1966, a group of Bulgarian engineers (including Vaptsarov) underwent three months of training at Renault’s facilities in France to prepare for local assembly.

- Atanas Taskov and Georgi Mladenov – Managers in charge of automobile exports at Bulet. They would later play a role in selling the cars abroad (sometimes beyond what Renault’s contract allowed, as noted later).

Politically, the Bulgarrenault venture had tacit approval from Todor Zhivkov’s communist government. Initially, Moscow did not object – in the mid-1960s, the Soviet Union had not yet begun mass car production (the Soviet-Fiat AvtoVAZ project was starting), and Bulgaria’s effort was seen as a small local initiative. There was a sense of friendly competition: seeing neighboring Romania pursue a deal with Renault around the same time, Bulgaria was keen not to be left behind. By launching Bulgarrenault in 1966–67, Bulgaria “beat Romania by a year” in starting Western-backed car production (Driventowrite). This East-West collaboration was viewed domestically as a bold move to elevate Bulgaria’s industrial capacity and give the country a bit of unique status within the Eastern Bloc.

After some delays, assembly began in early 1967. Renault 8 model kits were assembled in a makeshift facility (Hall #10 of the Plovdiv Trade Fair grounds). By the end of 1967, a dedicated automobile plant in Plovdiv was completed to house the production line. This new plant was equipped with a moving assembly conveyor and modern welding and painting equipment imported from the West (an investment of about US$ $15 million). The first Bulgarian-assembled Renault 8 sedans were unveiled to the public in February 1967, creating quite a stir – it was officially announced in the state enthusiast magazine Avto-Moto, which listed the price of the new car at 5,500 leva (later adjusted to 6,100 leva).

In summary, the historical context of Bulgarrenault is one of East-West economic pragmatism set against Cold War politics. Bulgaria’s leadership pursued the venture to gain technological know-how and prestige, leveraging Bulet’s financial resources and Metalhim’s industrial base. They did so with an awareness that Romania and others were seeking similar deals, thus it was partly a geopolitical strategy to not fall behind in auto manufacturing. For a brief period, this made Bulgaria the only Soviet-bloc country producing Western-designed cars on its soil – a fact trumpeted with pride.

Economic and Industrial Impact

From an economic perspective, Bulgarrenault was an ambitious undertaking for a small planned economy like Bulgaria’s. The venture required significant upfront investment and had mixed financial returns, but it did leave a notable industrial legacy.

Investment scale

Through Metalhim and Bulet, the Bulgarian government invested heavily in establishing car production. A brand-new assembly facility was built on the outskirts of Plovdiv (at Asenovgrad Road), equipped with modern automation. The plant featured a conveyor assembly line plus state-of-the-art welding and paint shops acquired from the West at a cost of about $15 million – a huge sum in the 1960s. Additional funds went into licensing fees (for example, ~8 million French francs paid to Alpine for rights and tooling to build the Alpine A110 locally). Bulet utilized its hard currency reserves to pay for knocked-down kits and machinery, trading Bulgaria’s export earnings (from other sectors) to import this automotive technology.

Production volume and costs

The original plan was to ramp up to thousands of cars per year (initially an ambitious goal of 3,000 per year, later even talk of 10,000/year by 1970) (Periodismodelmotor). In reality, total production fell short. Production lasted only about five years (1966–1970), with some leftover assembly in early 1971. In that period, roughly 4,000–6,500 cars were built (estimates vary). A contemporaneous count through 1970 was ~4,000 units (mostly Renault 8 and 10), while including the final 1971 batch brings it to around 6,500 (Bulgarian sources cite 6,540 cars of all types). This volume was an order of magnitude lower than what actual mass production would require. Economically, the venture struggled: almost all parts had to be imported from France, meaning each car carried a high import cost. Bulgarian records show that about US$ 6 million was spent on parts for the ~4,000 vehicles up to 1970, averaging $1,500 per car just in imported content. The selling price in Bulgaria was around 6,100–6,800 leva (for the R8 and R10) – roughly equivalent to $6,100–6,800 at the official rate, which left little room for profit after assembly costs. Indeed, an analysis later noted the production was not financially advantageous since “all parts were imported, with only the assembly done in Bulgaria,” and Renault calculated that a car assembled in Plovdiv cost more than one built in France. In short, the venture never achieved profitability. It was a subsidized project justified more by industrial policy than by immediate economic return.

Industrial and workforce development

Despite the poor financials, Bulgarrenault had a positive impact on Bulgaria’s industrial capability. It created hundreds of jobs – from assembly line workers to mechanics and engineers – fostering skills previously scarce in the country. Workers were trained in modern automotive assembly techniques, quality control, and machinery operation. A team of Bulgarian engineers spent three months in France in 1966, training at Renault’s factories, and returned to lead operations at home. This technology transfer was invaluable; those engineers gained know-how in everything from engine tuning to factory workflow, which they could later apply in other sectors. The Plovdiv plant itself introduced automation into Bulgarian manufacturing. According to reports, it had a fully automated moving line and the “most modern welding and painting aggregates of those years”, significantly advancing local technical standards. Moreover, the experience with fiberglass manufacturing for the Bulgaralpine sports car brought new chemical and materials engineering knowledge – Bulgaria even sourced fiberglass raw materials from East Germany and Poland and mastered molding techniques under Alpine’s license. Perhaps most impressively, the Bulgarrenault team gained enough confidence to attempt creating a home-grown car prototype just a year into the project. In 1968, engineers from the Plovdiv factory designed and built the “Hebros 1100” prototype, a front-wheel-drive fiberglass hatchback with a 1.1 L engine developed in Bulgaria (Autobild). While Hebros never went into production, its development (under Gen. Yamakov’s guidance) directly resulted from skills acquired through Bulgarrenault. This indicates the venture’s impact on technical education and innovation was significant, even if it wasn’t sustained.

Exports and foreign trade

One economic rationale for Bulgarrenault was reducing the need to import finished cars by building them locally. However, Bulgaria’s domestic market for cars was small and not very wealthy – the new Bulgarrenault 8 and 10, while cheaper than Western imports, were still expensive items for the average citizen (over 30 months of an average salary at ~6,000 leva). The Bulgarian side sought to export some of the production to recoup costs and earn hard currency. The contract with Renault originally stipulated that the cars were only for the domestic market, but soon Bulgaria breached this condition. Starting in 1968, batches of Bulgarrenaults were sold abroad:

- Yugoslavia: Approximately 500 units (all Renault 10 models) were exported to neighboring Yugoslavia between 1967 and 1969. Yugoslavia, though socialist, was non-aligned and had an open market for cars – these Bulgarian-assembled Renaults found buyers there, providing Bulgaria with convertible currency income.

- Austria: In 1970, around 300 (some sources say up to 900) Renault 8 and 10 cars were exported to Austria. Austria, a neutral Western country, appears to have been a surprising destination; possibly, an Austrian firm agreed to import some of the Bulgarian-built cars (perhaps attracted by a lower price). This move especially upset Renault since Austria was a market where Renault itself sold cars. Finding “Bulgar Renaults” there undercut the parent company’s distribution.

- Middle East: Several units were also sold to some Middle Eastern countries (exact figures are not documented, but likely a few hundred). Given Bulet’s trading connections, these could have been countries like Syria or Egypt with cordial relations with the Eastern Bloc. Exporting there would bring in hard currency or barter goods valuable to Bulgaria.

These exports show that international partnerships emerged not in manufacturing but in distribution – Bulgaria became an exporter of cars to other markets, which was unheard of for a Comecon economy then. However, this also sowed the seeds of conflict: Renault had not authorized Bulgaria to re-export the CKD-assembled vehicles to third countries. By doing so, Bulgaria violated the joint venture agreement. From Bulgaria’s perspective, selling abroad was a way to offset the venture’s cost (each exported car meant an inflow of hard currency). Indeed, Bulet’s mandate was to generate foreign exchange, and once domestic demand was partly met, they sought buyers abroad. However, from Renault’s perspective, Bulgaria was dumping Renault models in markets where Renault or its licensees operated, which was seen as unfair competition. As discussed in the comparative context section, this discord would come to a head in 1969–70.

The Bulgarrenault project had a mixed economic impact. It did not become a profitable enterprise – unit costs remained high, and the scale was too low to amortize the heavy investment in the new factory. A Bulgarian retrospective bluntly noted that between 1966 and 1971, about 6,540 cars were made, and “unfortunately, the production was unprofitable” since almost all inputs were imported (Classa). However, the broader industrial impact was positive in that it created a new industrial capability, provided jobs and training, and gave Bulgaria a taste of cutting-edge manufacturing. It also earned the country some hard currency through exports (approximately 1,773 cars were exported in total by early 1970). The experience would influence other sectors and future attempts (for instance, Bulgaria later built on its know-how to assemble trucks and buses, and decades later, to attract another car assembly venture with Rover in the 1990s). In the late 1960s, for a brief time, Bulgaria went from having no car industry to exporting cars abroad, a remarkable leap made possible by the Bulgarrenault initiative.

Technical Details: Models, Specifications, and Production Methods

Bulgarrenault produced three main models under the Renault collaboration – the Bulgar Renault 8, Bulgar Renault 10, and the “Bulgaralpine” A110 sports car – and developed a one-off prototype (Hebros). Technically, these vehicles were very similar to their French originals, with only minor local adaptations. Below is a detailed look at each:

Bulgarrenault 8

This was the local name for the Renault 8 (R8) assembled in Bulgaria. The R8 was a small family sedan with a rear-mounted engine and rear-wheel drive. It had a 4-door body with a very straightforward, boxy design. Early versions came with a 956 cc inline-4 engine (~44 hp), while later ones had an upgraded 1,108 cc engine (~50 hp). Notably, the R8 featured four-wheel disc brakes – an advanced feature for an economy car in the 1960s (Secret-classics). The Bulgarrenault 8s were assembled from CKD kits and were virtually identical to the French-made R8 in terms of specifications, performance, and appearance (Periodismodelmotor). The only difference was branding: they were marketed as “Bulgar Renault 8”. They reportedly bore a tricolor windshield sticker with the word “Булет” (Bulet) to signify the Bulgarian assembler, in addition to Renault badges. The interior, 4-speed manual transmission, suspension (independent all around), and other components were all per Renault’s design. In Bulgarian use, the R8 gained a reputation as a reliable and comfortable car, far more modern than the Soviet Moskvich models that had been common before. Approximately half of Bulgarrenault’s output was R8s.

Bulgarrenault 10

The Renault 10 (R10) was produced alongside the R8 and was a slightly larger, more refined version of the same car. It shared the rear-engine layout and most mechanicals with the R8. The R10’s body was stretched a bit at the front and rear for more trunk space, and it featured rectangular headlights (after a 1968 facelift) instead of the R8’s round lights. In Bulgaria, the R10 was assembled starting in 1968 and was positioned as a more upscale model. It used the 1,108 cc engine exclusively, producing about 46 hp and driving through a 4-speed manual gearbox (Secret-classics). Like the R8, it had disc brakes on all four wheels and a simple, robust rear swing-axle suspension. Again, no major design changes were made for local production – a Bulgarrenault 10 was a Renault 10 with Bulgarian assembly tags. Contemporary accounts noted that the Bulgarian-built cars were “completely French and only assembled on Bulgarian soil” (Periodismodelmotor), meaning build quality and features matched the original. The R10 was slightly more expensive than the R8 (6,800 leva vs 6,100 leva) due to its larger size. It was favored by those who wanted a roomier cabin and better trim. About 2,000 cars produced in Plovdiv were R10s (including nearly all of the exported units, as Bulgaria exported R10s first).

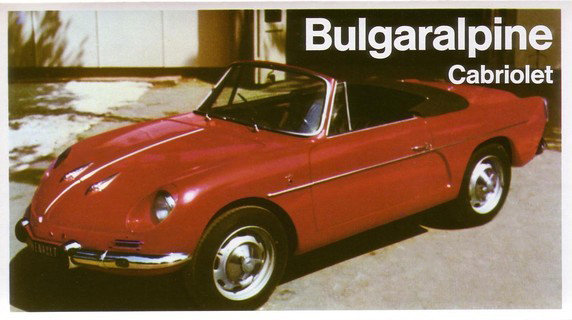

Bulgaralpine (Alpine A110)

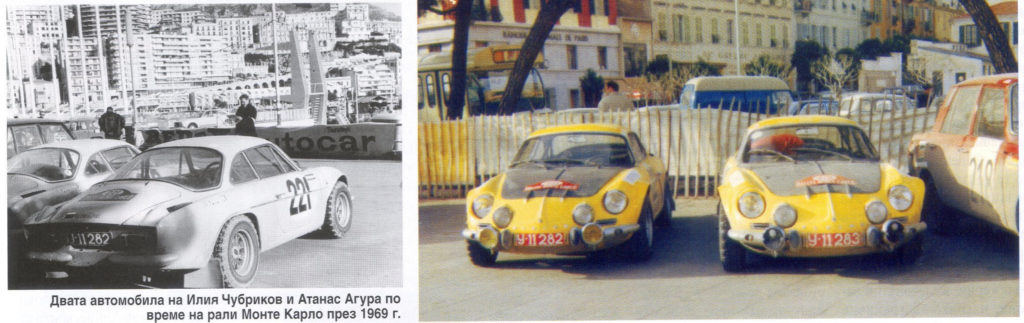

The Bulgaralpine was a licensed production of the Alpine A110 sports car – a project born from Bulgaria’s collaboration with Renault’s associate, Société Automobiles Alpine. The A110 was a two-seater rally sport coupe, famous for its sleek fiberglass body and rally wins. In late 1966, Alpine’s founder Jean Rédélé visited Sofia and struck a deal with Bulet to allow a limited assembly of Alpine cars in Bulgaria. This was an extraordinary addition to Bulgarrenault’s lineup: whereas other Eastern Bloc ventures focused only on utilitarian sedans, Bulgaria assembled a championship-caliber sports car. Technically, the Bulgaralpine A110s were built on a steel backbone chassis with a lightweight fiberglass body (molded in Bulgaria using imported resin and fiberglass mat). They were equipped with Renault engines – initially the 0.956 L (956 cc) from the R8 Major and later the 1.1 L (1,108 cc) from the R8 Gordini, both 4-cylinder units (Driventowrite). In street tune, these engines produced on the order of 55–70 hp, but they could be tuned higher. The cars had a 4-speed (sometimes 5-speed in rally prep) and rear-wheel drive, with a rear-engine placement. The performance was impressive for the era: 0–100 km/h in under 10 seconds and top speeds of 180+ km/h for the 1108 cc version. Bulgaralpines were painted in vibrant colors (a signature bright blue was standard), and a few were prepared as rally cars. In fact, Bulgaria formed a Bulet-sponsored rally team that campaigned the Bulgaralpine: in 1968, two Bulgaralpine cars, driven by the Chubrikov brothers and teammates, competed in the prestigious Monte Carlo Rally – marking the first Bulgarian entries ever in that event. While they didn’t win Monte Carlo, earlier in 1967, Iliya Chubrikov had driven a Bulgaralpine (or a prototype with an Alpine engine in an R8 body) to victory in the Transbalkania Rally, giving Bulgaria a notable motorsport triumph. The Bulgaralpine was not intended for the mass market; it was costly (priced at 8,200 leva new, roughly 1.3 times the cost of an R10) and was marketed to state-sponsored motoring clubs and well-heeled individuals. Only a small number were produced – sources variously cite 60 units (Classicauto) up to 120 units in total. (The production manager Iliya Chubrikov later recalled the number as “about 100”.) Regardless of the exact figure, this was a limited, almost hand-built production. Bulgaralpines were built from 1967 through 1969; none were made after 1969. Notably, while there were plans to export some (Bulgarian media mentioned 50 slated for export) (Marica), it appears nearly all stayed in Bulgaria, as the car was in high demand for local rallies and demonstrations. Technically, a Bulgaralpine is indistinguishable from a French Alpine A110 aside from branding – even the “Alpine” scripts and logos were used. Bulet did secure a perpetual license for the A110 (often referred to under the code name “Bularalpine”), meaning legally the brand “Bulgaralpine” remained Bulgarian-owned and the know-how was fully transferred. This unique sports car gave Bulgaria a presence in motorsport and is often remembered as the crown jewel of the Bulgarrenault experiment.

Production methods and technology

Bulgarrenault’s manufacturing process started with Complete Knock-Down (CKD) kits from Renault. These kits included all the car components (body panels, engine, transmission, wiring, interior, etc.), shipped to Bulgaria to be assembled on-site. In 1967, 100% of parts were imported – effectively, Bulgarian workers were bolting together French-made parts. The plan, however, was to localize production progressively. This meant gradually sourcing parts from Bulgarian suppliers or manufacturing them in-country. Indeed, by 1968, Metalhim had organized the production of specific components: Bulgarian factories started making small parts like wiring harnesses, battery trays, some trim pieces, and hardware. Impressively, Bulgaria even exported auto parts back to France as part of the arrangement – 16,000 “accessory kits” (probably wiring or other small components) were supplied to Renault in 1967, with a projection of 100,000 such units in 1968. This indicates a two-way technology exchange: not only were cars coming in, but Bulgaria was developing the capability to make components to Renault’s standards. The assembly line in Plovdiv was highly mechanized for its time – photographs from 1968–69 show a moving conveyor with cars at various stages, and workers performing tasks with pneumatic tools. The plant layout was designed with Renault’s input (somewhat mirroring a scaled-down version of Renault’s Flins factory). It even had automated welding robots for certain assemblies, which were cutting-edge in the Eastern Bloc. The painting section was fully enclosed with proper ventilation and used French-supplied paint materials. For the fiberglass body production of the Bulgaralpine, Bulgaria imported the necessary presses and molds from France, paying a license fee of 8 million francs. They initially imported the resin chemicals from France, but later sourced them from East Germany’s chemical industry. The fiberglass bodies were made in a workshop in Plovdiv – essentially a low-volume artisan process (fiberglass mat laid in molds), quite separate from the metal body assembly of the sedans. It’s worth noting that quality control was reportedly quite good: Renault had its advisors on-site, and Bulgarian workers took pride in meeting Renault’s specifications. Completed Bulgarrenault 8s and 10s underwent road testing and inspection. Many were displayed at trade fairs (the Plovdiv International Fair was a venue where the new cars were showcased annually). In September 1968, at the Plovdiv Technical Fair, Bulgarrenault not only exhibited the R8, R10, and Bulgaralpine but also unveiled the prototype Hebros 1100. The Hebros 1100 was a remarkable side-project: a modern hatchback with a locally engineered transverse 1.1 L engine (designed by Metalhim engineers in Sofia and built in a machine factory in Kazanlak) and a 5-speed transaxle. Its styled fiberglass body (hatchback design, painted metallic blue) incorporated parts scavenged from various Western cars – e.g., Fiat 124 bumpers and dashboard, Wartburg 353 headlights, Peugeot 204 wagon tail-lamps, Renault 16 steering wheel and gear lever – a creative solution due to lack of custom parts. Two running prototypes were made (one blue, one silver) with a top speed of around 150 km/h from the 1108 cc, ~60 hp engine (Autobild). While Hebros never saw production (the project was abandoned in 1969 as Bulgarrenault’s future became uncertain), it stands as proof of the technical confidence Bulgarrenault had instilled in Bulgarian engineers. They had gone from assembling foreign designs to conceiving their own hybrid vehicle in just a couple of years.

In technical terms, the Bulgarian Renaults were equal to their French counterparts. A Western observer in 1969 would have found little difference in driving a car off the Plovdiv line versus one from Renault’s own factories. This is illustrated by the fact that Renault 8s and 10s built in Bulgaria could be sold in markets like Austria without issue, meeting the required standards. The project brought Western automotive technology behind the Iron Curtain and, for a short time, made Bulgaria one of the most technologically advanced car producers in the Eastern Bloc (surpassed only by perhaps Czechoslovakia’s Tatra in terms of complexity). The trade-off, however, was heavy dependence on imported parts and know-how, which, as seen, had economic and political downsides. But from a strictly technical viewpoint, Bulgarrenault succeeded in creating a small line of cars that matched 1960s European norms, and even an exotic sports car that put Bulgaria on the rally map. The swift progress from zero to a functioning car plant was a notable feat of technology transfer and local adaptation.

Bulgarrenault vs. Other Eastern Bloc Auto Ventures

When comparing Bulgarrenault to other Eastern Bloc automobile production ventures of the same era, both similarities and stark differences emerge. The 1960s saw a trend of socialist countries seeking Western licenses to kick-start their automotive industries – but each country’s experience was shaped by its political relations and goals. Below, we compare Bulgaria’s effort with a few key peers: Romania’s Dacia, the Soviet Union’s Lada (VAZ), and East Germany’s Trabant (IFA).

Romania’s Dacia

Romania’s Dacia is perhaps the closest parallel to Bulgarrenault, as both involved Renault and began in the late 1960s. In 1966, Romania (under Nicolae Ceaușescu) signed a licensing deal with Renault to produce the R8, just as Bulgaria did. Romania’s first model, the Dacia 1100, was essentially a Renault 8 built at the new Colibași plant, and it entered production in 1968. By that time, Bulgaria was already assembling R8s (since early 1967). However, the two ventures diverged significantly in scale and longevity. Romania built an entirely new large factory from the ground up (with French assistance) and had a population roughly twice Bulgaria to serve. In 1969, Dacia introduced the Dacia 1300, based on the Renault 12 – a more modern front-engined, rear-wheel-drive sedan. This became the staple Romanian car for the next decade. Meanwhile, Bulgaria was winding down Bulgarrenault by 1970 without ever moving to newer models. Dacia, backed strongly by the Romanian state’s resources and a desire for some independence from Soviet economic dominance, produced cars throughout the 1970s and 1980s, even beyond the Renault license (modifying the R12 design in-house). In terms of numbers, Dacia dwarfed Bulgarrenault: for example, by the late 1970s, Dacia had produced hundreds of thousands of vehicles, whereas Bulgarrenault stopped at a few thousand. The key differences were political will and scale – Moscow allowed Romania a greater degree of economic independence. It was determined to fulfill local demand with local cars, while Bulgaria (much more aligned with Soviet policy) did not get such leeway. Technologically, in the early years, the Bulgarian and Romanian cars were similar (both R8s made from Renault kits). Romania’s Dacia even shared some early challenges – for instance, Dacia 1100 also struggled with quality initially and was produced only until 1971 before focus shifted entirely to the 1300. Where Bulgarrenault stood out was adding the Alpine sports car (Romania never produced an Alpine variant), but where it fell short was not transitioning to newer models like the Renault 12. Dacia became a lasting national car industry (and still exists today), whereas Bulgarrenault was a short-lived pilot project.

USSR’s Lada (VAZ)

The Soviet Union’s main automotive initiative of that era was the establishment of the VAZ plant in Togliatti, in collaboration with Italy’s Fiat. This resulted in the famous “Lada” or Zhiguli cars (the first model being the VAZ-2101, introduced in 1970, based on the Fiat 124). It’s important to note that the Soviet project was on a vastly different scale and had a different strategic role. The Soviets aimed to produce hundreds of thousands of cars annually for the entire Eastern Bloc. Indeed, VAZ was producing on the order of 220,000 cars per year by 1973 (and later up to 600,000/year), effectively flooding the socialist markets with relatively affordable cars.

In comparison, Bulgarrenault’s few thousand units total were a drop in the bucket. However, there is a direct connection: once the Lada project came online, it altered the political calculus for satellite countries like Bulgaria. Bulgaria, being one of the most loyal Warsaw Pact members, was expected to buy Soviet Ladas (and Moskviches) rather than make its own Western-designed cars. Soviet displeasure with Bulgaria’s independent venture became evident around 1969–1970. According to Bulgarian accounts, Leonid Brezhnev personally intervened after seeing the shiny Bulgarrenault models displayed at a Moscow auto exposition – the story goes that Brezhnev, with his well-known love of cars, frowned upon the “modern Western look” of the Bulgarian Renaults and questioned why a fraternal socialist country was making French cars instead of adopting Soviet models Shortly thereafter, an order “from Moscow” effectively forced Bulgaria to cease car production in 1970. While the exact details may be anecdotal, it aligns with the broader policy of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA or Comecon): the Soviets wanted to avoid duplication. They preferred that member countries rely on each other’s products. Since the USSR was now producing the Zhiguli (Lada) in large numbers (and at a lower cost due to economies of scale), in Moscow’s view, there was little rationale for Bulgaria to continue assembling Renaults. The closure of Bulgarrenault in 1970 coincides with the start of Lada exports to the Eastern Bloc in 1971. After 1970, Bulgaria dutifully became an importer of Soviet cars; Ladas became common on Bulgarian roads through the 1970s, essentially replacing the niche that Bulgarrenault might have filled. From a technical/policy perspective, Lada vs. Bulgarrenault highlights a contrast: Lada was a fully sanctioned socialist production (with Western help but Soviet controlled) designed to be sustainable, whereas Bulgarrenault was a semi-experimental joint venture that lacked high-level political backing when it conflicted with Soviet interests. Renault itself noted this – one reason Renault was keen on the Bulgarian deal in 1966 because the USSR at that time had no modern car for the populace, but by 1970 that gap was closing. In comparative terms, Bulgaria’s project was essentially steamrolled by the Soviet project. What stands out is that for a brief period, tiny Bulgaria was making cars arguably more sophisticated (rear disc brakes, etc.) than what the giant USSR was offering (the early Lada was robust but still a 1966 Fiat design with drum rear brakes). This discrepancy may have been politically uncomfortable. In any case, policy alignment with Moscow ultimately determined Bulgarrenault’s fate, in contrast to Dacia (which Romania kept going by keeping some distance from Moscow).

East Germany’s Trabant (and Wartburg)

East Germany (the GDR) followed a very different path – it did not engage in Western joint ventures for cars during the Cold War, instead continuing with its indigenous automobile industry centered around the IFA Trabant and Wartburg. The Trabant 601, produced from 1964 onward in Zwickau, was a minimalist people’s car with a 594 cc two-cylinder two-stroke engine making 26 hp. Its body was made of Duroplast (a plastic resin reinforced with waste cotton fibers), owing to steel shortages. The Wartburg 353 was a somewhat larger car (900 cc, 50 hp two-stroke) made in Eisenach. In the 1960s, these East German cars were already technologically outdated (the designs were rooted in 1950s engineering).

In comparison, the Renault 8/10 that Bulgaria assembled was far more modern: four-stroke engines, more power (~46 hp), reliable electrical systems, and even features like all-round disc brakes. For example, a 1970 Trabant had a top speed of about 105 km/h and smoky exhaust, whereas a 1970 Bulgarrenault 10 could top 135 km/h with much cleaner emissions. However, East Germany’s approach was driven by self-reliance; political constraints prevented them from partnering with Western firms (though they did import some Western tech for other industries). The result was that East German citizens had to wait many years for a very basic car, while Bulgarian citizens, for a short window, had access to a car on par with those driven in Paris or Rome. Bulgarrenault stood out in design by delivering Western-level comfort (heater, decent suspension) and styling, whereas the Trabant was infamously spartan. That said, East Germany’s model was sustainable within the socialist framework – they kept producing Trabants for decades (until 1990), fulfilling a transportation need despite the car’s obsolescence. Bulgaria’s model, while briefly superior in product, was not sustained. By the mid-1970s, Bulgarian drivers who wanted a new car mostly had to buy a Lada or Moskvich, putting them in a similar situation to East Germans (who queued for Trabants). One could argue Bulgaria’s venture was too ahead of its time and out of alignment with bloc policies, whereas East Germany’s was behind the times but fully in alignment. It’s also telling that after Bulgarrenault ended, Bulgaria did not attempt to make a “Trabant equivalent” – it simply abandoned personal car production entirely, focusing on other vehicle types (like forklifts, trucks, and later buses by Chavdar). In terms of design/technology comparisons, Bulgarrenault’s Renault 8/10 were conventional 1960s European cars (rear-engine, steel body) – comparable to contemporary Skoda models in Czechoslovakia (which had a 1.0L rear-engine sedan in the ’60s) or Poland’s FSO (which in 1967 started building the Fiat 125p under license). The Trabant’s fiberglass body vs. Bulgaralpine’s fiberglass body is an interesting juxtaposition: one was a cheap solution to make an underpowered economy car, the other a high-performance solution to make a rally car. They show two very different uses of polymer body technology in the East. The Wartburg 353 (another Eastern Bloc car) had a 50 hp two-stroke 1.0L engine – still inferior to Renault’s four-stroke – and it wasn’t until the late 1980s that Wartburg got a licensed four-stroke engine from VW. By that time, of course, Bulgarrenault was long gone.

Overall, Bulgarrenault’s uniqueness in the Eastern Bloc was that it introduced Western vehicles early and even dabbled in sports/racing cars, whereas most other Bloc ventures stuck to basic family cars (and usually with full Soviet endorsement). If we compare policy alignment, Romania’s Dacia was somewhat anomalous like Bulgarrenault, but Romania’s independent streak allowed it to continue; Yugoslavia’s Zastava (not mentioned in the question, but another comparison) also built Fiats under license and could do so as a non-aligned country. Bulgaria, on the other hand, was not free to go against Soviet wishes for long. When Brezhnev signaled disapproval, Bulgaria complied and sacrificed its car industry to keep Moscow happy.

Bulgarrenault cars did not fall short in design and technology – they were on par with Western designs and in many ways ahead of the home-grown Soviet-bloc vehicles in the late ’60s. However, in terms of policy and longevity, it fell short: it wasn’t integrated into a long-term national strategy and ultimately clashed with the bloc’s direction. A Western classic-car publication, reflecting on this history, noted that Renault ended the project after around “3,500 vehicles” and that it “came tumbling down in 1970” due to the export breach and political factors. Meanwhile, Dacia and Lada became household names in their countries.

Bulgarrenault was a bold but brief experiment, whereas ventures like Dacia and Lada were more entrenched and enduring (the former by navigating a semi-independent path, the latter by being the socialist establishment’s flagship). In the design dimension, Bulgaria’s cars stood out positively – they didn’t lag behind Western models at all – but in the dimension of production volume and continuity, Bulgaria lagged far behind the likes of Dacia (which became a true mass producer). Bulgaria initially stepped outside the typical Soviet-bloc comfort zone in policy alignment, but by 1970 it was pulled back in line, illustrating how Cold War politics ultimately overrode economic logic.

Legacy of Bulgarrenault

Although Bulgarrenault operated for only a few years, it left a lasting legacy in Bulgaria’s cultural memory and industrial heritage. Decades later, people still talk about these cars with a mix of nostalgia and intrigue, and a few physical remnants survive as collector items and museum pieces.

Cultural significance and public perception

In the late 1960s, Bulgarrenault cars became a source of national pride. Ordinary Bulgarians were proud (and perhaps astonished) to see a locally made car that could rival Western vehicles. The fact that Bulgaria – a small socialist country – was building Renaults even became part of national propaganda. Contemporary newspapers lauded the achievement; for example, when the first Bulgarrenault 8 was sold, it was trumpeted that Bulgaria was now the only country in the socialist camp producing Western cars. The Bulgaralpine sports car especially captured the public’s imagination: it was beautiful, fast, and winning rallies – a stunning symbol that Bulgaria could do high-tech things. When Iliya Chubrikov won the 1967 Transbalkania rally in a Renault-Alpine (the first big international rally victory for Bulgaria) and later when Bulgarian teams entered the Monte Carlo Rally in 1968 with Bulgaralpines, it created a sensation. Photos of those blue Bulgaralpines with the Bulgarian flag colors were widely circulated. Even the Bulgarrenault sedans, though far humbler, represented modern comfort that the average Bulgarian had rarely experienced in a car. Public perception at the time was very favorable – these cars were seen as a coveted product (albeit too expensive for many – a new Bulgarrenault cost several years’ wages). Only a relatively small number of people actually owned them, often nomenklatura or well-to-do professionals, but people would see them on the streets of Sofia or Plovdiv and feel a sense of progress. Today, the legacy is remembered fondly. Bulgarrenault is often discussed as a “missed opportunity” or a golden moment of ingenuity in Bulgarian popular culture and media. The venture’s abrupt end (often blamed on outside political forces) adds a layer of victim narrative that resonates in post-Cold War reflections. For instance, Bulgarian articles have titles like “How the comrades destroyed Bulgarrenault because of the Zhiguli” (Marica), pointing fingers at internal politics and Soviet pressure. In general, Bulgarrenault carries a positive connotation of national pride and technological achievement that was sadly cut short.

Surviving models and collector interest

Given the low production run, it’s no surprise that Bulgarrenault vehicles are rare today. However, a handful do survive. Enthusiasts in Bulgaria have managed to save and restore some of the cars. Bulgarrenault 8/10: A few R8s and R10s assembled in Bulgaria are known to exist in drivable condition. These are usually in the hands of classic car collectors. For example, there have been YouTube videos showcasing a 1968 Bulgarrenault 8 with its original features intact, and Bulgarian classic car clubs occasionally display a Bulgarrenault at shows. Some of these cars sat unused for decades and have needed full restoration. The good news for restorers is that mechanically, they are identical to the more common Renault 8/10, so spare parts can be sourced from abroad (France or Romania, where Dacia 1100 parts are similar). Bulgaralpine: Surviving Bulgaralpines are even rarer gems. It’s believed that at least several of the ~100 Bulgaralpines built still exist. One notable example is owned by a Bulgarian collector Teodor Osikovski, who has lent it to the Retro Classic Car Museum in Kapatovo, Bulgaria. This car, a 1968 Bulgaralpine A110 painted blue with racing decals, is on display and looks immaculate – it even has the number 18 and “Monte Carlo Rally” plaque on the hood, commemorating the rally heritage【34†】. Internationally, because the Bulgaralpine is an Alpine A110 in all but name, it is very interesting to Alpine enthusiasts. Alpine A110s are iconic and valuable now, and a Bulgarian-built example is an exotic variant. Occasionally, photos of Bulgaralpines circulate in Western classic car circles, eliciting fascination that an Alpine was made in Bulgaria. As for the Hebros 1100 prototypes, it’s unclear if either of the two still exists; there are rumors one survived in a warehouse, but nothing confirmed. The collector’s interest in Bulgarrenaults is growing as more people learn about this chapter of history. Within Bulgaria, there’s nostalgia among older folks who remember the cars, and among younger car enthusiasts who see it as a “lost treasure” of Bulgarian automotive history. Clubs such as the Bulgarian Classic Car Union have members on the lookout for Bulgarrenault artifacts. Even parts of Bulgarrenaults (like an engine or nameplate) are considered collectible. In recent years, some custom car workshops (like Vilner, a high-end Bulgarian customizer) have restored Bulgarrenault interiors to like-new condition, showing that there’s domestic appreciation for these vehicles beyond just stock restoration.

Museum and documentation

Bulgaria has made efforts to document and preserve the Bulgarrenault legacy. The Retro Cars Museum (Zlaten Rozhen) mentioned above is one example where the public can see a Bulgaralpine up close. There is also a Transportation Museum in Sofia and a Technological Museum; it’s reported that at least one Bulgarrenault 8 is in a museum collection (possibly the National Polytechnic Museum in Sofia) though it may not always be on display. Local historians have kept the story alive in Plovdiv, the city where the cars were built. The Plovdiv archive and local press have published articles with titles like “Archives of Plovdiv: How the Bulgarrenault factory was annihilated because of the Zhiguli”, indicating they have records and are sharing them with the public. These articles often include interviews with former workers. For instance, engineer Dimitar Mitev, who was a senior technologist at the factory, has recounted details of the production process and the shutdown in Bulgarian media. A documentary film was made (as hinted in one source) with firsthand accounts. Much of the historical documentation (contracts, technical drawings, photos) survived. “Marica” (a Plovdiv newspaper) obtained a copy of the original license contract for the Alpine, discovering that it was a perpetual license with the brand name “Bular” – meaning legally Bulgaria still holds rights to “Bulgaralpine” as a brand. While that has no practical effect today, it’s a fascinating archival fact. There are also preserved issues of the Avto-Moto magazine from 1967 that announced the Bulgarrenault launch and listed the car prices. Some of these historical materials are on display or accessible through archives, ensuring that Bulgarrenault’s story is recorded for posterity.

Legacy in hindsight

With the benefit of hindsight, Bulgarrenault’s legacy is often discussed in terms of “what if?”. Many Bulgarian commentators wonder what might have happened if the venture had continued. Could Bulgaria have evolved its own car makes, like how Dacia did? Was it a missed chance to have a permanent auto industry? These questions are debated, though most concede that, given Bulgaria’s economic size and Soviet pressures, continuing would have been very difficult. Nonetheless, Bulgarrenault left behind a legacy of innovation and a demonstration that Bulgarian workers and engineers could meet world standards when given the opportunity. Psychologically, it broke the ice – after Bulgarrenault, the idea of technological cooperation with the West became less unthinkable (Bulgaria later engaged in things like computer technology exchange, and in the 1980s even built the Rodacar prototype in a second attempt at car-making). In the immediate decades after, however, Bulgaria focused on other niches (like heavy trucks, forklifts, etc.) and the Bulgarrenault episode became a proud memory rather than a forward path.

Today, at classic car shows in Bulgaria, a preserved Bulgarrenault 8 with its distinctive round headlamps and Bulet sticker in the window can still draw a crowd. It represents a different trajectory from the one the Bulgarian industry once took. Enthusiasts keep the flame alive through clubs and online forums, sharing the few photos from the factory floor in 1968, or the black-and-white images of Chubrikov’s Bulgaralpine flying through a rally stage. In popular narratives, there is often a tinge of lament that politics cut short a promising enterprise – for example, Bulgarrenault is sometimes cited as a victim of “Brezhnev’s eyebrows” (a colorful way to say a single disapproving look from the Soviet leader killed the project) This has entered local lore and underscores how people view the project: as something positive that was unjustly curtailed by higher powers.

The legacy of Bulgarrenault is one of pride, nostalgia, and lesson-learning. Pride in that Bulgaria proved capable of joining the automotive world; nostalgia for the stylish “Bulgar Renaults” that once turned heads in Sofia; and lessons about the importance of economic viability and political context in such ventures. Historically, Bulgarrenault has become a fascinating case of East-West collaboration. It is well-documented in both Bulgarian and international automotive history circles as an example of Cold War-era industrial cooperation. And although it did not survive past 1971, it paved the way for future collaborations (indeed, decades later in the 2000s, Renault-Nissan would partner with Romania’s Dacia and other Eastern European producers – one wonders if the roots of trust were laid in those early 1960s deals).

The surviving cars, the museum exhibits, and the rich archive of information ensure that Bulgarrenault is not forgotten. Instead, it is celebrated today as a bold chapter in Bulgarian industrial history. The venture’s story – from its hopeful start, through technical triumphs, to its premature end – offers a microcosm of the broader Cold War economic tug-of-war. For Bulgaria, it remains a reminder of what the country’s engineers and workers could achieve, and it holds a romantic spot in the nation’s collective memory.

Sources

- Wikipedia (Automotive industry in Bulgaria) – details on the Bulet-Metalhim joint venture and production figures – en.wikipedia.org

- AllCarCentral Magazine – summary of the Bulgarrenault project and total cars produced – allcarcentral.com

- Losange Magazine (Renault historic publication) – notes on production in 1969 and exports to Yugoslavia and Austria – periodismodelmotor.com

- Driven To Write – “Come and Meet my Sisters” (2024) – analysis of Alpine A110 license productions, including Bulgarrenault’s rise and fall – driventowrite.com

- Marica.bg (Bulgarian news) – archival research on Bulgaralpine and Bulgarrenault (license details, production numbers, rally participation) – marica.bg

- Classa.bg – “Nostalgia for old cars under socialism” – provides final production figure of 6,540 and notes the unprofitability of the venture – classa.bg

- Secret-Classics.com – “55 Years of Renault 10” – mentions Bulgarrenault 8/10 and that Renault ended the project after ~3,500 cars – secret-classics.com

- ClassicAuto.bg (Retro Museum) – Bulgaralpine A110 exhibit info (production years 1967–69, unclear total 60 vs 120 – )classicauto.bg

- Periodismo del Motor (Spanish) – “Bulgarrenault, cuando la colaboración…” – historical overview emphasizing Bulgaria’s motives and the numbers produced/exported – periodismodelmotor.com

- Take a look at the Bulgaralpine catalog.