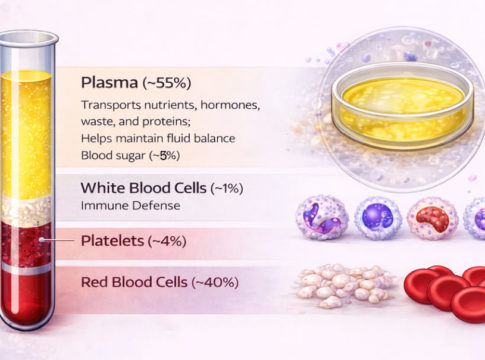

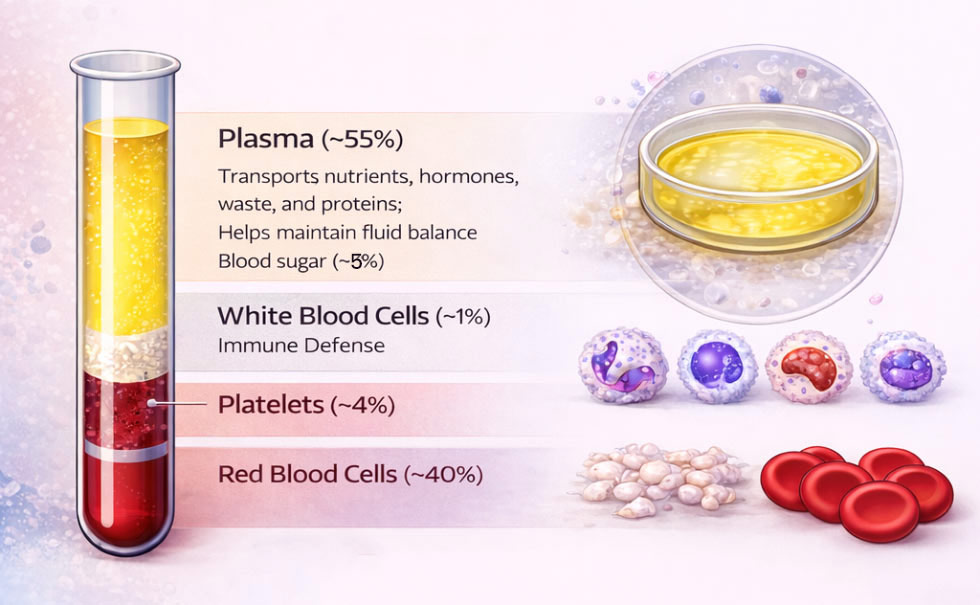

Blood is a specialized connective tissue and a circulating body fluid that supports almost every organ system. It functions as a transport medium, a defense system, and a regulator of internal conditions (homeostasis). In humans, blood is typically described as having four main components: plasma, red blood cells (RBCs), white blood cells (WBCs), and platelets.

At a basic structural level, blood is organized into:

- Plasma (the liquid phase)

- Formed elements (cells and cell fragments): RBCs, WBCs, platelets

In simplified classroom models, dissolved nutrients such as glucose (“sugar”) may be treated as a separate “component” for calculations. Scientifically, however, glucose is a solute carried in plasma, not a separate structural component of blood.

Plasma (liquid matrix of blood)

Plasma is the liquid component of blood and accounts for approximately 55% of blood volume (hematology.org). It is roughly 90% water and contains dissolved substances essential for transport and regulation, including:

- Proteins (for example, antibodies and clotting factors)

- Nutrients (glucose, amino acids, lipids)

- Hormones

- Ions/salts (essential for osmotic balance and nerve/muscle function)

- Waste products (metabolic by-products destined for removal)

Key functions of plasma

- Transport medium

Plasma transports blood cells and distributes dissolved substances (e.g., nutrients and hormones) to tissues (hematology.org). - Waste removal support

Plasma transports waste products to organs involved in filtration and detoxification, especially the kidneys and liver (hematology.org). - Immune and clotting support

Plasma contains antibodies and clotting proteins. These antibodies are part of the blood group system and react against incompatible blood group antigens during transfusions, while clotting proteins interact with WBCs and platelets during immune responses and hemostasis.

Red blood cells (RBCs, erythrocytes)

Red blood cells are the most abundant formed element and account for roughly 40–45% of blood volume (hematology.org). This fraction is related to hematocrit, a clinical measure often used to estimate the proportion of RBCs.

Structure

- RBCs are biconcave discs, which increase surface area relative to volume and support efficient gas exchange (hematology.org).

- Mature RBCs lack a nucleus, leaving more internal space for hemoglobin.

Key function: gas transport

- RBCs transport oxygen from the lungs to body tissues using hemoglobin.

- They also transport carbon dioxide from tissues back to the lungs for exhalation.

- RBCs carry blood group antigens (A, B, and Rh) on their surface, which determine a person’s blood group and are essential for blood compatibility.

Production and lifespan

- RBCs are produced in the bone marrow through erythropoiesis, regulated by the hormone erythropoietin.

- A typical RBC lifespan is approximately 120 days, after which they are removed and recycled.

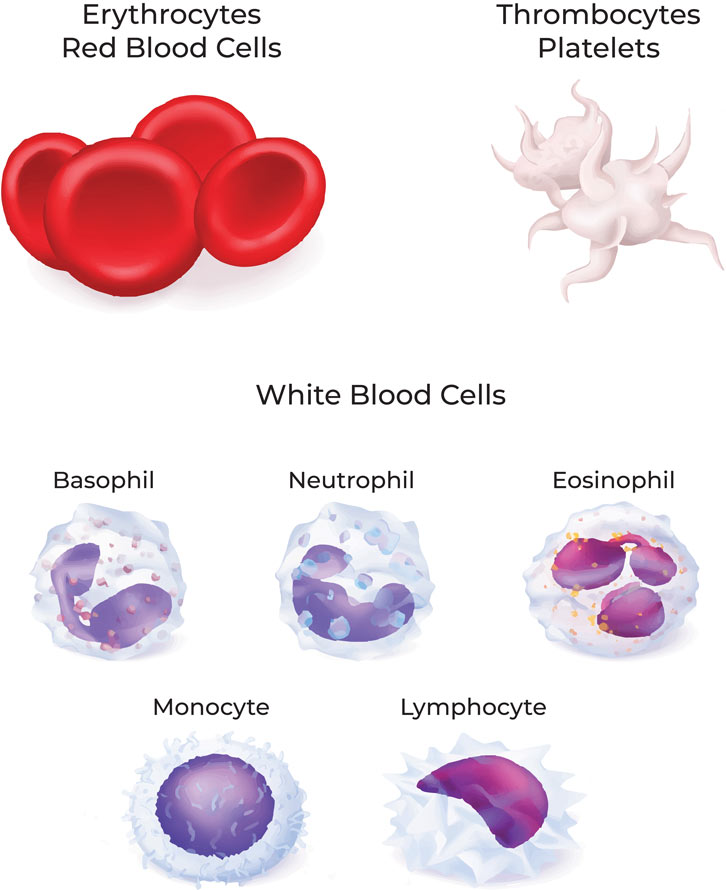

White blood cells (WBCs, leukocytes)

White blood cells constitute a much smaller fraction of blood volume (often estimated at approximately 1% in simplified models), yet they are essential for immune defense.

Primary function: protection

WBCs protect the body against pathogens and abnormal cells by:

- Detecting threats

- Attacking invaders directly

- Coordinating immune responses

- Producing immune “memory” after infections and vaccinations

Examples of WBC types and roles

- Neutrophils: rapid responders that engulf bacteria and debris through phagocytosis.

- Lymphocytes: include cells that recognize specific pathogens and support antibody production.

During infection, the body can increase WBC production to strengthen the immune response.

Platelets (thrombocytes)

Platelets are cell fragments derived from bone marrow cells and are specialized for hemostasis (the process of stopping bleeding).

Key function: blood clotting

When a blood vessel is damaged:

- Platelets adhere to the injured site.

- They form a temporary platelet plug (hematology.org).

- They release factors that trigger a clotting cascade.

- This converts fibrinogen (a plasma protein) into fibrin, forming a mesh that stabilizes the clot.

This clot both prevents blood loss and provides a scaffold for tissue repair.

Blood circulation and how blood supports organ systems

Circulation pathway (overview)

Blood circulates through the body due to the pumping action of the heart and the structure of the vascular network:

- Arteries carry blood away from the heart.

- Arteries branch into arterioles and then into capillaries, where exchange occurs.

- Blood then returns through venules and veins back to the heart for re-oxygenation.

Figure placeholder (no text on image):

Figure: Diagram of blood circulation. The heart pumps blood through arteries into ever-smaller arterioles and capillaries, and then it collects into venules and veins before returning to the heart.

How blood supports key body systems

Immune system support

Blood is a delivery route for immune defense:

- It transports WBCs to sites of infection, where they can engulf and destroy pathogens.

- It distributes antibodies (in plasma) and immune signals.

- Vaccines introduce harmless antigens that stimulate WBC activity and antibody production, creating faster responses later.

Nutrient delivery and waste removal

Blood delivers oxygen and nutrients to tissues (hematology.org) and transports wastes away:

- Carbon dioxide is carried back to the lungs.

- Other wastes are transported to the liver and kidneys for processing and elimination (hematology.org).

Hormone transport and pH regulation

Hormones (e.g., insulin and adrenaline) circulate in the blood to reach target organs.

Plasma also contains buffers and salts that help stabilize blood pH and fluid balance, supporting homeostasis.

Thermoregulation (temperature control)

Blood helps regulate temperature by redistributing heat:

- When cooling is needed, blood vessels near the skin dilate, increasing blood flow to the surface and allowing heat to escape.

- When conserving heat, vessels constrict, reducing heat loss.

This helps maintain a stable internal temperature near 37°C.

Summary (high-yield scientific recap)

- Plasma (about 55%) is the liquid component of blood that transports substances and contains proteins involved in clotting and immunity.

- Red blood cells (about 40–45%) carry oxygen and carbon dioxide via hemoglobin; they are biconcave and lack a nucleus.

- White blood cells (about 1% in simplified models) defend the body through immune responses such as phagocytosis and antibody-related protection.

- Platelets trigger clotting and, with plasma proteins, form stable fibrin clots to stop bleeding and support healing.

- Blood circulation enables transport, immune defense, waste removal, hormone signaling, and temperature regulation.

Glossary

- Plasma: the liquid part of blood containing dissolved substances

- Formed elements: RBCs, WBCs, platelets

- Hemoglobin: oxygen-binding protein in RBCs

- Phagocytosis: engulfing and digesting pathogens or debris

- Hemostasis: stopping bleeding via clot formation

- Fibrinogen/fibrin: clotting protein (inactive) and its active fibrous form

- Homeostasis: maintaining stable internal conditions

Sources & References

- American Society of Hematology (ASH) – Blood Basics: Components of Blood and Their Functions – hematology.org

- NHS Blood and Transplant (UK) – Why blood is necessary / blood components and functions – blood.co.uk