Blood functions as a delivery system in the body, carrying oxygen and nutrients. But not all blood is the same. If someone needs a blood transfusion (a transfer of blood from a donor to a patient), physicians must carefully match blood types. If the wrong type is given, the patient’s immune system can attack the donated blood, which can be dangerous. Why does this happen? The answer lies in tiny markers on our blood cells, called antigens, and in special proteins in our plasma, called antibodies. In this article, we’ll explore the two most important blood group systems – ABO and Rh – and learn how they determine blood type and inheritance.

What are Antigens and Antibodies?

Antigen: An antigen is any substance that can trigger an immune response. In the context of blood groups, antigens are specific molecules located on the surface of red blood cells. You can think of antigens as name tags on the cell. If your immune system sees an antigen it doesn’t recognize as “self,” it will consider it foreign.

Antibody: An antibody is a protein produced by the immune system that binds to a specific antigen. Antibodies float in the blood plasma (the liquid part of blood). If they encounter a matching foreign antigen, they bind to it, marking the cell for destruction. You can imagine antibodies as Y-shaped security guards that patrol your blood, looking for intruders.

How they relate to blood type: Your blood type is defined by which antigens you have on your red blood cells, and your immune system will produce antibodies against the antigens you do not have. For example, if your red cells have an “A” antigen, your immune system will see “B” antigen as foreign and make antibodies against B. If a foreign red blood cell with an unrecognized antigen enters your body, antibodies will bind to those cells. This causes the foreign red blood cells to clump (a process called agglutination) and be destroyed. This is precisely what can happen if someone receives the wrong blood type in a transfusion – the recipient’s antibodies attack the donor’s blood cells.

The ABO Blood Group System

One of the most critical blood group systems is ABO. The ABO system was the first to be discovered and is vital for safe transfusions. It has four main blood types: A, B, AB, and O. The type you have depends on which antigens are present on your red blood cells:

- Type A: Has A antigens on the red blood cells. The plasma (the fluid) of type A people naturally contains anti-B antibodies. In other words, their immune system is programmed to attack cells that express B antigens (because their own cells express only A antigens). If type A individuals encounter red blood cells bearing the B antigen, anti-B antibodies bind to those cells and mark them for destruction.

- Type B: Has B antigens on the red cells. Type B individuals have anti-A antibodies in their plasma. Their antibodies will attack cells that carry A antigens.

- Type AB: Has both A and B antigens on the red cells. People with type AB blood lack anti-A and anti-B antibodies in their plasma because their bodies recognize both A and B as self-antigens. (Their immune system sees both antigens on their own cells, so it doesn’t make antibodies against either.)

- Type O: Has neither A nor B antigens on the red cells. Think of type O as having “zero” of these antigens. Because they lack both A and B antigens, type O individuals’ plasma contains both anti-A and anti-B antibodies. Their immune system will attack any red cell that has A or B antigen (i.e., most foreign blood except another O type).

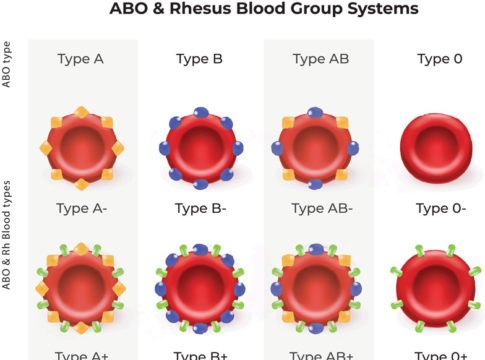

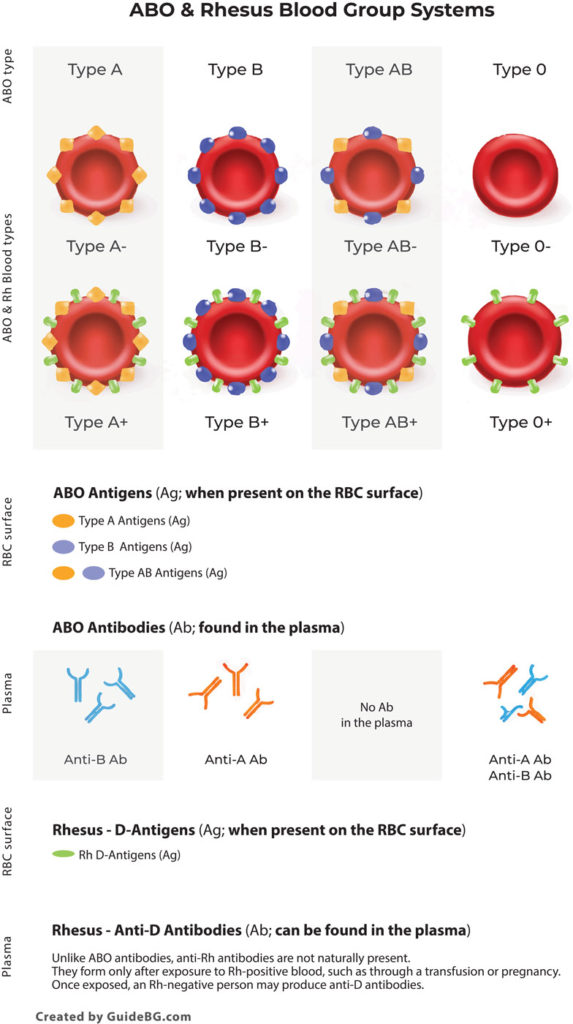

ABO blood groups. Each red blood cell has specific antigens on its surface (A antigens are shown as red pentagons, B antigens as blue diamonds). The plasma contains antibodies (Y-shaped symbols) against the other type. Type A blood has A antigens on RBCs and anti-B antibodies in plasma. Type B has B antigens and anti-A antibodies. Type AB has both antigens and no anti-A or anti-B antibodies. Type O has no A/B antigens and both anti-A and anti-B antibodies.

Why these antibodies are present: Interestingly, people develop anti-A or anti-B antibodies early in life, even without having received a transfusion. This is thought to occur due to exposure to bacteria or to foods containing molecules similar to A and B antigens, thereby training the immune system. Thus, if a person with type A blood receives type B blood, their anti-B antibodies will immediately recognize the B antigens as foreign and attack them.

What Happens in an ABO Mismatch?

If an individual is given the wrong ABO blood type, a potentially dangerous reaction can occur. For instance, imagine a type B patient accidentally receives type A blood. The patient’s anti-A antibodies will bind to the donated type A red cells. This causes red blood cells to clump and lyse. The patient may develop fever and chest and back pain, and blood vessels may become clogged with debris from destroyed cells. Such an acute hemolytic transfusion reaction is a medical emergency – it can lead to kidney failure or even death if not treated. In fact, the most common cause of death from blood transfusions is a clerical error leading to an ABO-incompatible transfusion. This is why hospitals are cautious about blood type matching before transfusion.

ABO Compatibility: Who Can Receive What?

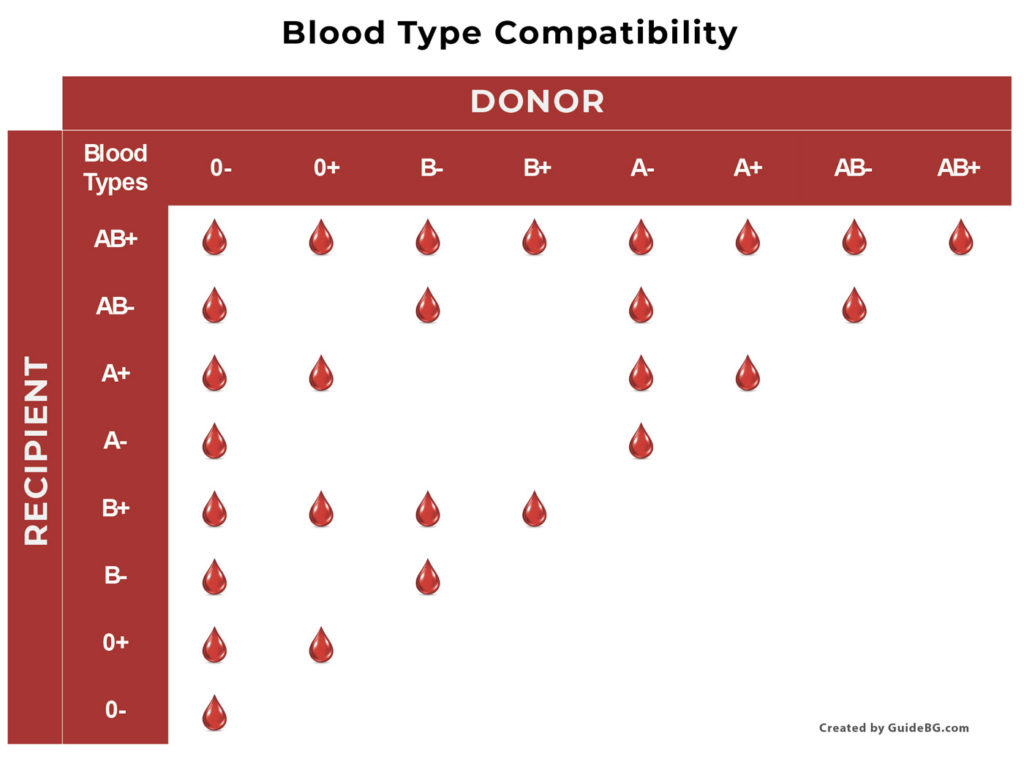

The rule of thumb for ABO compatibility is that you must not present an antigen to someone that their immune system will recognize as foreign. In practice, this means:

- A person with type A blood can safely receive A blood (which has A antigens) because their body is used to A, and also O blood (which has no antigens). They cannot receive B- or AB blood because those blood groups contain B antigens, which would be recognized by anti-B antibodies in the patient’s plasma.

- A person with type B blood can receive B blood and O blood. They cannot receive A or AB blood (they would have anti-A antibodies).

- A person with type AB blood can receive A, B, AB, or O blood. AB individuals are often referred to as “universal recipients” for ABO because they lack anti-A and anti-B antibodies. Their immune system won’t attack A or B antigens, allowing them to accept any ABO type. (However, Rh factor still matters, as we’ll see later.)

- A person with type O blood can only receive O blood. Type O plasma has both anti-A and anti-B antibodies, so it will attack any donated blood that has A or B antigens. Type O people are limited in what they can receive. Still, conversely, their blood has no A/B antigens, so O negative is known as the “universal donor” type for red blood cells – type O blood can be given to anyone with any ABO type without causing an ABO reaction.

Let’s summarize ABO compatibility from the recipient’s point of view:

- Type O: Can receive only type O blood (no A or B antigens allowed).

- Type A: Can receive type A (matches their antigen) or type O (no antigens). Not from B or AB.

- Type B: Can receive type B or type O. Not from A or AB.

- Type AB: Can receive any type (A, B, AB, O) – no ABO restrictions.

Now, the donor’s point of view: The flip side of the above is who each type can donate to:

- O -> can donate to A, B, AB, and O (universal RBC donor).

- A -> can donate to A and AB (recipients who won’t react to A antigen).

- B -> can donate to B and AB.

- AB -> can donate to AB only (since AB blood has both antigens, only an AB recipient lacks antibodies against both).

ATL: Communication Activity – Explaining ABO Blood Types

Imagine you are a science communicator explaining blood groups to someone who has no background in biology. In a short paragraph or presentation, describe the differences between blood types A, B, AB, and O, including what antibodies each type has. Make sure to explain why receiving the wrong blood type can be dangerous. Focus on communicating clearly and logically. For example, how would you explain to a classmate why a person with type O can donate to anyone, but can only receive type O? This activity will help you practice organizing information and conveying it in simple terms.

Jump into Blood Typing – Forward and Reverse Blood Typing, Logic, Steps, and Transfusions

The Rh Factor (Rhesus System)

In addition to the ABO system, another key antigen divides blood into positive (+) or negative (-) types. This is the Rh factor. When you hear blood types like “A-positive” or “O-negative,” the positive/negative refers to the Rh factor. Rh stands for Rhesus, because it was first discovered through research on rhesus monkeys.

What is the Rh factor? It is a protein antigen that can be present on red blood cells. The most critical Rh antigen is called the D antigen. If your red blood cells have the D antigen, you are Rh-positive (Rh⁺). If you do not have it, you are Rh-negative (Rh⁻). For example, someone with A+ blood has the A antigen and the Rh (D) antigen on their cells; someone with A− blood has the A antigen but not the Rh (D) antigen.

- About 85% of people are Rh-positive, and around 15% are Rh-negative in the general population (these percentages can vary among ethnic groups). Being Rh-negative is not an illness; it’s just a genetic trait, like having a specific eye color.

Antibodies and Rh: Unlike the ABO system, people do not automatically have anti-Rh antibodies in their plasma. A Rh-negative person’s immune system typically has to be exposed to Rh-positive blood to start making anti-Rh antibodies. Exposure can happen through a mismatched transfusion or, commonly, during pregnancy (an Rh-negative mother carrying an Rh-positive baby). Once an Rh-negative person’s immune system has been sensitized (taught to recognize Rh as foreign), they will produce anti-D antibodies.

Why is the Rh factor important? Two major reasons:

- Transfusion reactions: If an Rh-negative person receives Rh-positive blood, their immune system can become sensitized and produce anti-Rh antibodies. The first mismatched transfusion might not cause an immediate reaction (if they’ve never seen Rh before, it takes time to develop antibodies), but it will prime their immune system. A second exposure to Rh-positive blood could then trigger a severe immune response, destroying the donated red blood cells. Therefore, as a general rule, Rh-negative patients should receive only Rh-negative blood, whereas Rh-positive patients may receive blood from Rh+ or Rh– donors. In practice, when matching blood for transfusion, both ABO and Rh are considered to avoid any reaction.

- Pregnancy (Hemolytic Disease of the Newborn): During pregnancy and birth, an Rh-negative mother can be exposed to her Rh-positive baby’s blood. The mother’s immune system may then produce anti-Rh (anti-D) antibodies. These antibodies generally won’t harm the first baby, but they remain in the mother’s circulation. In a subsequent pregnancy with another Rh-positive baby, the mother’s antibodies can cross the placenta and attack the baby’s red blood cells. This condition is known as hemolytic disease of the newborn (erythroblastosis fetalis). It can cause anemia and jaundice in the baby and can be very serious. Thankfully, doctors prevent this by giving Rh-negative mothers an injection called RhoGAM after the first birth (this medication destroys any Rh-positive cells before the mother’s immune system reacts, so she doesn’t become sensitized). Modern prenatal care has made this condition much rarer.

The Rh factor adds another layer to blood typing: every ABO type is either “+” or “–”. For safe transfusions, the Rh status of donor and recipient should be matched whenever possible. A Rh-negative patient should receive Rh-negative blood to reduce the risk of developing antibodies. An Rh-positive patient can safely receive Rh-negative blood (there’s nothing foreign in Rh-negative blood for their immune system to react to), and they can receive Rh-positive blood since they themselves have the Rh antigen and won’t see it as foreign.

Combining ABO and Rh: Complete Blood Types and Compatibility

Every person’s blood type has two components: the ABO type (A, B, AB, or O) and the Rh type (positive or negative). For example, someone might be B+, meaning type B and Rh-positive, or O-, meaning type O and Rh-negative. In total, there are eight common blood types (A+, A-, B+, B-, AB+, AB-, O+, O-).

When considering blood transfusions, both ABO and Rh compatibility are considered. Here are some essential points about combined compatibility:

- O-negative (O−) blood is the universal donor for red blood cells. O-negative has no A or B antigens and no Rh antigen, so it’s the least likely to cause any immune reaction in an emergency. This is why, in trauma situations or when a patient’s blood type is unknown, O- blood is often used. However, O- is relatively rare (only about 7% of people are O-), so it’s precious.

- AB-positive (AB⁺) blood is the universal recipient type. An AB+ person has A and B antigens (so no anti-A or anti-B antibodies) and also has the Rh antigen (so they won’t make anti-D). This means an AB+ patient can receive red blood cells of any type (A, B, AB, or O, positive or negative) without their immune system attacking the donor cells.

- Rh-negative patients (of any ABO type) should ideally receive Rh-negative blood. For example, if someone is A-, they should get A- or O- blood, not A+ or O+.

- Rh-positive patients can receive Rh+ or Rh- blood of the appropriate ABO type. For instance, a B+ person can safely get B+ or B- (and O+ or O- if needed, since O is ABO-compatible with anyone), because Rh- poses no threat to an Rh+ individual.

- For ABO, as discussed earlier, matching the letters is key (with O as a wild-card donor and AB as a wild-card receiver). A+ can get A or O (with appropriate Rh), B+ can get B or O, etc. A- can get A- or O-, and so on.

It’s a lot to remember, but medical staff use the Blood Type Compatibility Chart to check these rules.

Inheritance of Blood Groups

Blood groups are inherited traits, just like eye color or hair color. Each biological parent passes down genes that determine the child’s blood type. Let’s look at how inheritance works for the ABO system and the Rh system:

Inheritance of ABO Blood Types

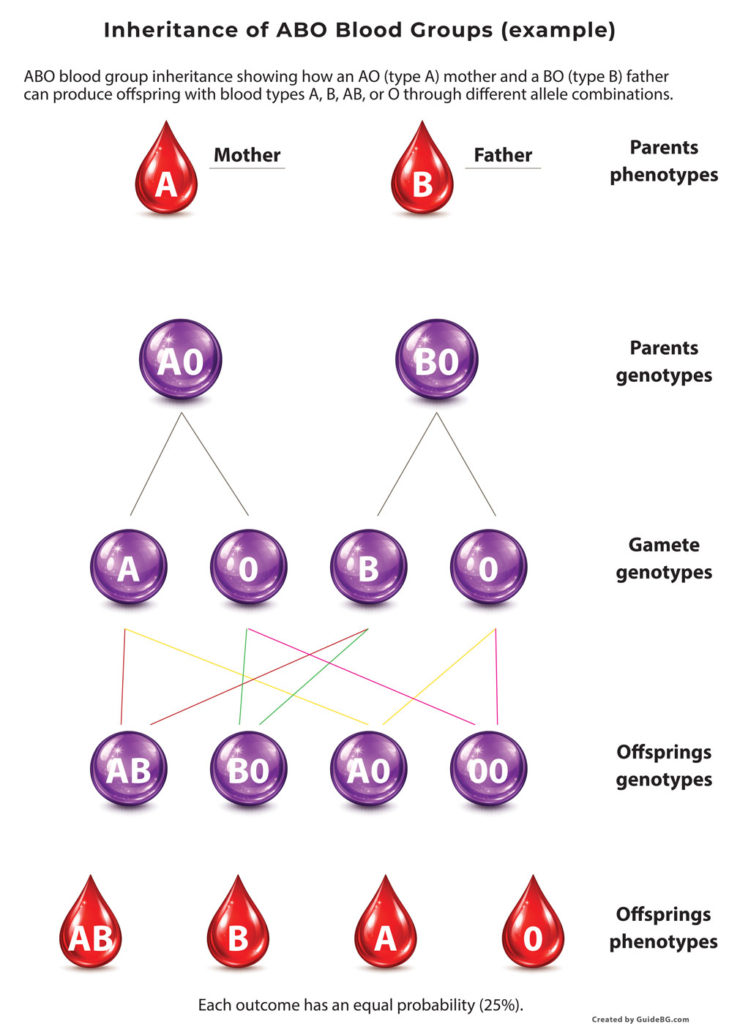

The ABO blood type is controlled by a single gene (called ABO). This gene comes in three versions (alleles): A, B, or O. Every person has two copies of the ABO gene – one inherited from their mother and one from their father. The combination of the two alleles determines the blood type:

- The

Aallele codes for the A antigen. - The

Ballele codes for the B antigen. - The

Oallele doesn’t produce a functional antigen (essentially, it means “no A or B antigen”).

Inheritance pattern: The A and B alleles are codominant, which means if you have one of each, both antigens will be expressed. In contrast, O is recessive, meaning it doesn’t produce an antigen and is hidden if paired with A or B. In simpler terms:

- A and B dominate over O. If someone inherits an

Afrom one parent and anOfrom the other, their blood type will be A (because the O doesn’t add any antigen). Similarly,B+Oyields type B. - A and B together (A + B) result in type AB – both antigens show up.

- O + O yields type O (no A or B antigen at all).

Here are the possible genotype combinations and their resulting phenotypes (blood types):

- AA or AO genotype -> Type A blood (A antigen expressed; O is silent).

- BB or BO genotype -> Type B blood.

- AB genotype -> Type AB blood (both A and B antigens expressed).

- OO genotype -> Type O blood (no A/B antigens).

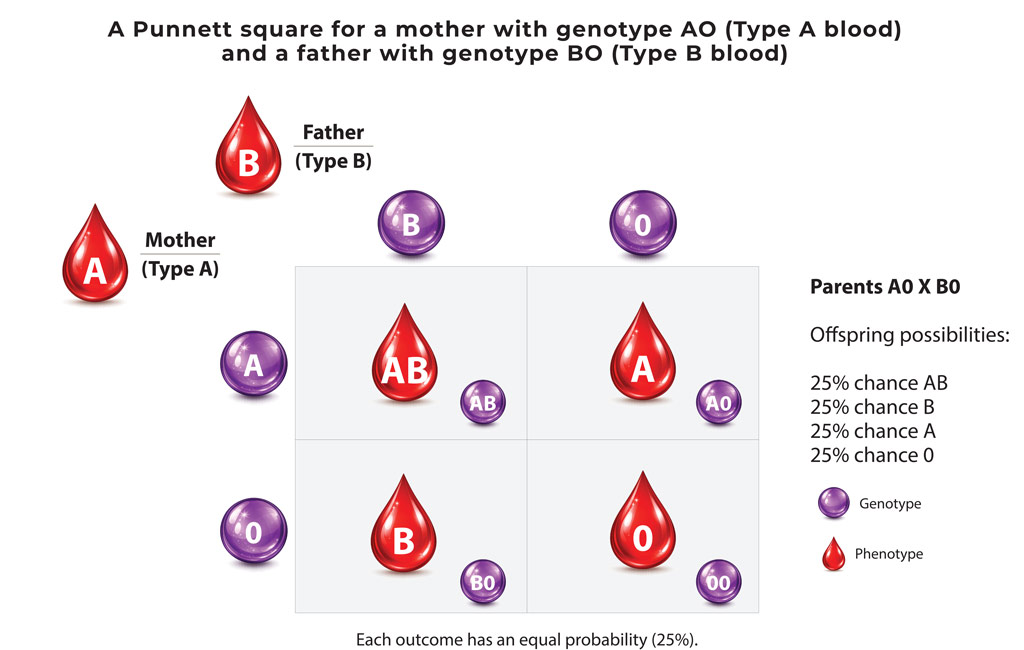

For example, if a mother is type A and a father is type B, their genotypes can determine the children’s blood types. Let’s say the mother’s genotype is A O (she’s type A, carrying one O allele) and the father is B O (type B, carrying O). We can use a Punnett square to predict their children’s possibilities:

Using the example above:

- There is a 25% chance for a child with the genotype

A B(one allele from each) which would be type AB. - 25% chance for genotype

A Owhich is type A. - 25% chance for genotype

B Owhich is type B. - 25% chance for genotype

O Owhich is type O.

Indeed, an A (with O hidden) and B (with O hidden) couple can have children of any of the four ABO types – this is a classic example. On the other hand, some pairings have more limited outcomes. For instance, if one parent is type O (OO) and the other is type AB (AB), the children will either be type A or type B. (The AB parent can only pass an A or a B allele, and the O parent can only pass O. The combinations would be A O (type A) or B O (type B). You would get 50% A and 50% B, and no AB or O child in that specific cross.)

Another example: Two type O parents (OO x OO) can only have type O children, since both always pass the O allele. And two type AB parents (AB x AB) cannot have an O child either (since neither parent has an O allele to give – their children can be A, B, or AB). Genetics can sometimes yield surprises, but these basic patterns hold as long as we’re only dealing with the normal ABO alleles.

Inheritance of the Rh Factor

A different gene determines the Rh factor. For simplicity, we’ll discuss the gene that controls the presence of the D antigen (there are multiple genes in the Rh system, but D is the primary one for the +/– type). Each parent gives one version of this gene to the child:

- Let’s use

Rto represent the Rh-positive version (the allele that does produce the D antigen). - And

rto represent the Rh-negative version (allele that produces no D antigen).

The R allele is dominant over r. This means:

R Rgenotype -> Rh-positive (obviously, has D antigen).R rgenotype -> Rh-positive (has D antigen, because the one R allele is enough to produce it).r rgenotype -> Rh-negative (no D antigen, since neither allele produces it).

So a Rh-negative person must be r r (two negative alleles). A Rh-positive person could be either R R or R r. Approximately 85% of people carry at least one R and are Rh+.

What combinations are possible? If both parents are Rh-negative (r r and r r), then all children will be r r Rh-negative. If one parent is Rh+ and the other Rh-, it depends on whether the Rh+ parent is R R or R r. For example, suppose the mother is Rh-negative (r r) and the father is Rh-positive. If the father is genetically R r (heterozygous), he has a 50% chance of passing R and 50% chance of passing r. The mother can only pass r. The children could be R r (Rh+) or r r (Rh-) with equal probability (50/50). If the father were R R (homozygous dominant), then all children would inherit an R from him and be Rh+.

Notice from the figure and explanation: Two Rh-positive parents can indeed have an Rh-negative baby, but only if both parents are carriers of the recessive r allele. In everyday terms, both parents might be “+” but each carries a hidden “-” that can pair up in the child. On the other hand, if both parents are Rh-negative, none of their children will be Rh-positive (since they have no R allele to pass on).

ATL: Critical Thinking Exercise – Solving a Blood Type Puzzle

Scenario: A baby is born with Rh-negative blood, but both of the parents are Rh-positive. How is this possible? Using what you know about genetics, explain or draw a Punnett square to show how two Rh⁺ parents could produce an Rh⁻ child. (Hint: Think about the R and r alleles.) Now consider ABO blood types: For example, if a child is blood type O but the father is type AB, what does that tell you about the mother’s genotype? Write a short explanation for each situation. This will test your ability to apply inheritance patterns to real-world cases, an essential critical-thinking skill in genetics.

Through this exploration, you should now be able to explain why a patient’s blood type matters so much, determine compatibility for transfusions, and even work out family blood type genetics with a Punnett square. Blood might be red everywhere, but it’s the subtle differences at the microscopic level that make each type unique and essential to identify. This knowledge is not only fundamental to science classes but has also saved millions of lives by making blood transfusions safe and effective.

Terms & Dictionary

Gene

A gene is a section of DNA that contains instructions for making a specific trait or characteristic.

In the ABO blood group system, the ABO gene encodes the antigens that appear on red blood cells.

Allele

An allele is a version of a gene.

The ABO gene has three common alleles: A, B, and O. Each person inherits one allele from each parent.

Genotype

A genotype is the combination of alleles a person has for a particular gene.

Examples:

- AO

- BO

- AB

- OO

Genotype refers to the genetic makeup, not the observable phenotype.

Phenotype

A phenotype is the observable trait that results from a genotype.

In blood groups, the phenotype is the blood type:

- Genotype AO → Phenotype A

- Genotype AB → Phenotype AB

- Genotype OO → Phenotype O

Gamete

A gamete is a reproductive cell (sperm or egg) that carries only one allele for each gene.

Gametes are formed by meiosis and combine during fertilization.

Example:

- A parent with the genotype AO produces gametes that carry either A or O.

Homozygous (Homozygote)

A homozygous individual has two identical alleles for a gene.

Examples:

- AA (type A)

- OO (type O)

Heterozygous (Heterozygote)

A heterozygous individual has two different alleles for a gene.

Examples:

- AO (type A)

- BO (type B)

- AB (type AB)

Inheritance

Inheritance is the process by which genes and alleles are passed from parents to offspring.

Blood types are inherited according to specific genetic rules.

Dominant

A dominant allele is expressed in the phenotype even if only one copy is present.

In the ABO system:

- A and B are dominant over O.

Recessive

A recessive allele is expressed only when two copies are present.

In the ABO system:

- O is recessive (blood type O appears only with genotype OO).

Codominant

Codominance occurs when two different alleles are both expressed in the phenotype.

In blood groups:

- A and B are codominant, producing blood type AB.

Punnett Square

A Punnett square is a diagram used to predict possible genotypes and phenotypes of offspring based on parental genotypes.

Each box represents an outcome with equal probability.

Antigen (Ag)

An antigen is a molecule on the surface of a cell that can be recognized by the immune system.

In blood groups, antigens are found on red blood cells (A, B, and Rh antigens).

Antibody (Ab)

An antibody is a protein found in blood plasma that binds to specific antigens.

Antibodies help the immune system recognize and respond to foreign cells.

Compatibility

Compatibility refers to whether donor blood can be safely given to a recipient without causing an immune reaction.

Compatibility depends on antigens on donor red blood cells and antibodies in the recipient’s plasma.

Probability

Probability is the chance that a specific outcome will occur.

In a 2×2 Punnett square, each possible genotype has a 25% probability.

Key Takeaway

Genes have different alleles; alleles combine to form a genotype, which determines the phenotype, and these combinations are passed to offspring through gametes.

References and Further Reads

- American Society of Hematology (ASH) – Blood Basics: Components of Blood and Their Functions

Use for: clear definitions of blood components; strong medical authority. - American Society of Hematology (ASH) – Blood Basics: Blood Types / Matching (ABO & Rh overview)

Use for: ABO/Rh fundamentals in a patient-friendly but accurate format. - NHS Blood and Transplant (UK) – Blood types (ABO and Rh)

Use for: straightforward explanations of blood groups and why they matter. - NHS Blood and Transplant (UK) – “What’s your type?” (who can give blood to whom / compatibility guidance)

Use for: clear donor/recipient rules and transfusion logic by type. - Canadian Blood Services – Blood type compatibility (donor–recipient compatibility)

Use for: compatibility charts used in educational settings; apparent organization. - OpenStax (peer-reviewed open textbook) – Multiple alleles & codominance (ABO inheritance support)

Use for: explaining ABO inheritance (A and B codominant; O recessive) and Punnett squares. - MedlinePlus (U.S. National Library of Medicine / NIH) – Blood typing (blood type test)

Use for: student-accessible medical explanations; good for confirming basic statements. - Stanford Blood Center – Rh inheritance (“Can two Rh+ parents have an Rh− child?”)

Use for: a clear, commonly used Rh inheritance explanation with Punnett-square logic.