What Is Blood Typing and Why Is It Important?

Blood typing is the process of determining a person’s blood group. Humans have different blood types, and not all blood types are compatible. This became clear in the early 20th century when Karl Landsteiner discovered the ABO blood groups in 1901. Before this discovery, blood transfusions were often hit-or-miss – sometimes they saved lives, but other times patients fell severely ill because their blood clumped (agglutinated) when mixed with incompatible blood. We now know that a blood type mismatch can cause a potentially fatal immune reaction. Thus, knowing a patient’s blood type and matching it with a compatible donor is critical before any blood transfusion.

In simple terms, blood typing checks for special markers on red blood cells and antibodies in the plasma that determine a person’s blood group. By identifying these markers (called antigens) and antibodies, physicians ensure that the donor’s blood will “mix” safely with the patient’s blood. If the wrong type is given, the patient’s immune system will attack the donor blood cells, causing them to clump (agglutinate), which can block blood vessels and lead to dangerous reactions. This is why blood typing matters so much: it prevents life-threatening transfusion reactions and has made modern transfusions safe and routine.

Landsteiner’s work earned him a Nobel Prize, and it laid the foundation for safe blood banking. Today, blood typing is a standard procedure whenever someone donates or receives blood.

The ABO Blood Group System

The ABO system is the main classification of human blood types. It is based on whether red blood cells have antigen A, antigen B, both, or neither on their surface. The four ABO blood types are:

- Type A: Has antigen A on red blood cells. (Only the A antigen is present on the cell surface.)

- Type B: Has antigen B on red blood cells. (Only the B antigen is present.)

- Type AB: Has both A and B antigens on red blood cells.

- Type O: Has neither A nor B antigen on red blood cells.

Importantly, your blood plasma naturally carries antibodies (Ab) against any ABO antigen you don’t have on your own cells. This means:

- If you are type A, your plasma has anti-B antibodies (antibodies that will attack B antigens).

- If you are type B, your plasma has anti-A antibodies.

- If you are type AB, your plasma has no anti-A or anti-B antibodies (because your body sees both A and B as “self”).

- If you are type O, your plasma contains both anti-A and anti-B antibodies (because O red blood cells lack both antigens, the body treats both A and B as foreign).

These antigen-antibody (Ag-Ab) relationships are why matching blood types is so important. For example, a type A person’s anti-B antibodies would attack type B blood if it were transfused, causing dangerous clumping of the donor cells. Likewise, a type O person has antibodies against both A and B, so they cannot safely receive A, B, or AB blood without a reaction. On the other hand, type AB individuals have no ABO antibodies at all, so they won’t react to type A or B blood – this makes AB blood the universal recipient type for red blood cell transfusions. Conversely, type O negative blood cells have no A, no B, and no Rh antigens (more on Rh below), so almost anyone’s immune system will accept O− red cells – people with O− are often called universal donors of red blood cells.

Key point: In a transfusion, you must never give someone red blood cells with an antigen against which their plasma contains antibodies. If you do, the recipient’s antibodies will attack the incoming cells. For instance, transfusing type A blood to a type B patient is dangerous because the patient has anti-A antibodies that will agglutinate (clump and destroy) the type A cells. The compatibility rules can be summed up simply:

- Type A individuals can safely receive blood from A or O (O has no antigens to trigger anti-B).

- Type B individuals can safely receive from B or O.

- Type AB individuals can receive from A, B, AB, or O (they are universal recipients because they lack anti-A and anti-B antibodies).

- Type O individuals can only receive from O (they have both anti-A and anti-B antibodies that would react with any A or B antigens).

Fact: In most populations, O+ (O positive) is the most common blood type (about 37–40% in many regions), whereas AB− (AB negative) is one of the rarest (around 1%). This is why O+ blood is often in high demand, and AB− donors are very unique!

The Rhesus (Rh) Factor

In addition to ABO, the other key blood group system in transfusions is the Rhesus factor, commonly the Rh D antigen. Red blood cells either have the Rh D antigen (Rh-positive) or lack it (Rh-negative). We denote this with a “+” or “−” after the ABO type (for example, A+ means type A with Rh antigen; A− means type A without Rh). Combining ABO and Rh, there are 8 common blood types (A+, A−, B+, B−, AB+, AB−, O+, O−).

Rh matching is also important for safe transfusions:

- If someone is Rh-positive (Rh+), they have the Rh D antigen and can receive blood from either Rh+ or Rh− donors (Rh− blood contains no antigen that their immune system would attack).

- If someone is Rh-negative (Rh−), they lack the D antigen and typically do not have anti-D antibodies in their plasma unless they have been exposed to Rh+ blood previously (e.g., through a prior transfusion or during pregnancy). However, if Rh− individuals receive Rh+ blood, their immune system may recognize the D antigen as foreign and produce anti-D antibodies. This sensitization can cause dangerous reactions in future transfusions or pregnancies. For this reason, in transfusions, Rh-negative patients are usually given Rh-negative blood only to be safe. Rh-positive patients can safely receive Rh+ or Rh− blood.

Rh factor is especially significant in pregnancy: an Rh-negative mother carrying an Rh-positive baby can produce antibodies that attack the baby’s red cells. To prevent this, Rh-negative mothers are given a medication (anti-D immunoglobulin) to avoid developing those antibodies. In transfusion practice, matching the Rh type (when possible) avoids these immune complications.

Summary: When determining compatibility, both ABO and Rh are considered. For example, if a patient is B− (B-negative), the ideal donor blood type would also be B−. In an emergency, B− could also receive O− (O negative) blood, since O− has no A, no B, and no Rh antigens – nothing that the patient’s immune system would reject. This makes O− the universal donor for red blood cells in emergencies, and AB+ the universal recipient (since AB+ individuals have all three major antigens and thus lack antibodies against A, B, and Rh).

Forward vs. Reverse Blood Typing: Two Ways to Check Blood Type

When lab technicians or students determine someone’s ABO blood type, they actually perform two complementary tests: forward typing and reverse typing. These are also known as cell typing (forward) and serum typing (reverse). They are like opposite mirror images of each other, and together they ensure accuracy. Here’s how they work:

Forward typing (direct ABO test)

This test looks for which antigens (Ag) are present on the patient’s red blood cells. A technician mixes a drop of the patient’s blood (which contains their red cells) with known antibody solutions: separately, one containing anti-A antibodies and another containing anti-B antibodies. These testing solutions are called antisera. If red blood cells carry the A antigen, anti-A serum will cause the cells to clump (agglutinate) because the antibodies bind to the A antigens. If the red cells carry the B antigen, the anti-B serum will cause clumping. The pattern of agglutination indicates the blood type: for example, if a blood sample clumps with anti-A but not with anti-B, it indicates that the cells have the A antigen only, so the blood type is A. If it clumps with both anti-A and anti-B, the cells have both antigens (type AB). If it clumps with neither, the cells lack both A and B antigens, indicating type O.

Forward typing is basically asking: “What antigen flags are on these red cells?”

Rh (D) typing is usually performed concurrently with forward ABO typing.

In this step, the patient’s red blood cells are mixed with anti-D (Rh) serum. If agglutination occurs, the blood type is Rh positive (Rh⁺); if no agglutination occurs, the blood type is Rh negative (Rh⁻). Unlike ABO typing, Rh typing lacks a reverse (plasma) confirmation test because individuals do not naturally produce anti-D antibodies unless they have been previously exposed to Rh-positive blood.

Reverse typing (indirect confirmation test)

This test identifies which antibodies (Ab) are present in the patient’s plasma to confirm the forward type. The plasma (the liquid part of blood without cells) contains the natural ABO antibodies we discussed earlier. In reverse typing, the technician mixes the patient’s plasma with known type A and type B red blood cells (prepared reagent cells with known antigens). Note that plasma will agglutinate any red blood cells that have an antigen the patient’s own blood lacks. A type A person’s plasma contains anti-B; when mixed with type B cells, it causes clumping, whereas with type A cells, it does not. A type B person’s plasma has anti-A and will clump type A cells but not type B cells, and so on. For example, if our patient’s plasma agglutinates the B test cells but not the A test cells, this confirms the patient is type A (their plasma contains anti-B antibodies that react with B cells, and no anti-A antibodies). Reverse typing is basically a double-check: the result should mirror the forward type. Both tests must agree before the ABO blood group is confirmed.

Reverse typing asks: “What antibodies does this person’s plasma already have, and what do they attack?” It should align with the antigens identified in forward typing.

To make this clearer, consider each blood type’s expected reaction pattern in forward vs. reverse tests:

- Type A blood: Forward test – clumps with anti-A serum, no clumping with anti-B. Reverse test – patient’s plasma clumps B cells (because it has anti-B), no clumping with A cells.

- Type B blood: Forward test – clumps with anti-B, not with anti-A. Reverse test – plasma clumps A cells (have anti-A), not B cells.

- Type AB blood: Forward – clumps with anti-A and anti-B (both antigens present). Reverse – no clumping in either A or B cell test (plasma has no antibodies against A or B).

- Type O blood: Forward – no clumping with anti-A or anti-B (no antigens on RBC). Reverse – plasma clumps both A and B test cells (since type O plasma has both anti-A and anti-B antibodies).

If forward and reverse typing do not match (an ABO discrepancy), it indicates an issue that requires investigation before transfusion. In practice, laboratories will not report a blood type until both the direct and reverse tests match.

It’s important to understand the concept rather than the minutiae: forward typing identifies the blood cell’s ID tags (antigens, Ag), and reverse typing checks the immune system’s watchdogs (antibodies, Ab) to make sure the identification is correct. They are complementary tests that should yield the same final blood group result.

Comparison of Forward and Reverse Blood Typing (ABO System)

| Feature | Forward Typing (Cell Typing) | Reverse Typing (Serum Typing) |

|---|---|---|

| Main purpose | Identifies which antigens (Ag) are present on the patient’s red blood cells | Identifies which antibodies (Ab) are present in the patient’s plasma |

| Key question asked | “What ID tags (antigens) are on the red blood cells?” | “What antibodies does the plasma already have, and what do they attack?” |

| What is tested | Patient’s red blood cells | Patient’s plasma (serum) |

| What is added | Known antisera: Anti-A and Anti-B | Known reagent red cells: Type A cells and Type B cells |

| What causes clumping (agglutination) | Antibodies in the antisera bind to matching antigens on red cells | Antibodies in the plasma bind to antigens on the reagent red cells |

| Agglutination means | The tested antigen is present on the red blood cells | The corresponding antibody is present in the plasma |

| No agglutination means | That antigen is absent from the red blood cells | That antibody is absent from the plasma |

| Role in blood typing | Primary test to determine ABO group | Confirmation test that must match the forward result |

| Antibodies in the plasma bind to antigens on the red cells | Identifies the blood group directly | Double-checks accuracy before transfusion |

| Laboratory rule | Must agree with reverse typing | Why is it needed |

How Blood Typing Kits and Trays Work in Practice

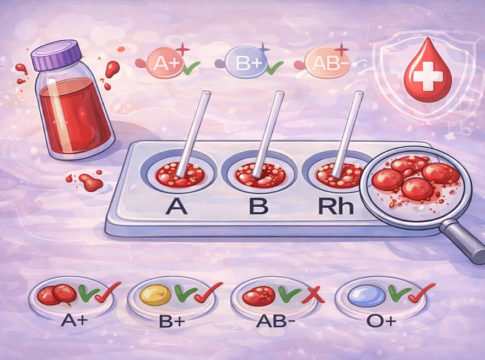

In laboratories and classrooms, blood typing is often performed using a blood typing kit with a plastic tray (or slide) containing small wells or circles labeled A, B, and Rh. These labels correspond to the tests for A antigen, B antigen, and the Rh factor (forward blood typing). The design of the tray helps organize the test so we don’t mix anything up. Here’s how a typical blood typing procedure is carried out (often as a hands-on activity in science classes, using simulated blood and reagents):

- Label and Prepare the Tray: Obtain a blood typing slide or tray and label the three wells: A, B, and Rh. If you are testing more than one sample, label each tray with the person or sample name (for example, “Patient X”) to keep track.

- Add the Blood Sample: Using a dropper, put one drop of the blood sample into each of the three wells on the tray. For real lab tests, this would be a diluted blood sample; in class kits, it might be synthetic or animal blood. Each well now contains the person’s blood.

- Add Anti-A Serum to the A Well: Add a drop of Anti-A antibody solution to the well labeled “A”. This reagent contains antibodies that specifically target A antigens. In many kits, the anti-A serum is colored blue for easy identification.

- Add Anti-B Serum to the B Well: Add a drop of Anti-B antibody solution to the “B” well. (Often, this reagent is colored yellow in kits.) This serum has antibodies that bind to B antigens.

- Add Anti-Rh (Anti-D) Serum to the Rh Well: Add a drop of Anti-Rh antibody solution to the “Rh” well. This tests for the Rh D antigen (the tray may label it “Rh” or “D”). The anti-Rh serum is usually clear or colorless.

- Mix and Wait: Gently stir each mixture in its well with a clean mixing stick or toothpick. (It’s important to use different stirrers for each well to avoid cross-contamination—we don’t want to accidentally transfer antibodies from one well to another.) Ensure the blood and serum are well mixed. Then, let the tray sit for a minute or so.

- Observe for Agglutination: Inspect each well to determine whether agglutination (clumping) has occurred. Agglutination can appear as grainy or gel-like clumps in the liquid, whereas no agglutination means the mixture remains uniformly red and liquid. Sometimes, gently tilting the tray can help you determine whether the red blood cells have clumped.

- Interpret the Results: Determine the blood type based on where you see clumping:

- If you observe clumping in the A well, it indicates that the blood cells have A antigens (the anti-A serum has found its target and caused clumping). If no clumping in A well, no A antigen. If you observe clumping in the B well, it indicates the presence of B antigens. No clumping means no B antigen. Clumping in the Rh well means the Rh antigen is present (Rh positive); no clumping in the Rh well means Rh negative.

- Clumping in A and Rh wells (but not B) = A+ blood type (A positive).Clumping in B and Rh wells (but not A) = B+.Clumping in A and B wells, but not Rh = AB− (A and B antigens present, Rh antigen absent).Clumping only in Rh well (and not in A or B) = O+ (no A/B antigens, but Rh present).No clumping in any well = O− (no A, no B, and no Rh antigens).

After interpretation, students or technicians will often record the results in a table (e.g., marking “agglutination: yes or no” for each well) and then record the determined blood type. The tray can be washed and reused if it’s a plastic kit, or disposed of if it’s a single-use card. In professional laboratories, the same principles apply, but tests may be performed in test tubes or specialized gel cards. Regardless of the format, the core idea is the same: mix blood with known reagents and observe clumping.

Before a Transfusion: Ensuring a Safe Match (Pre-transfusion Testing)

In a hospital setting, determining a patient’s blood type is just one part of making sure a blood transfusion will be safe. Hospitals follow strict procedures before any blood unit is administered to a patient. This process is often referred to as “type and crossmatch”. It includes:

- ABO and Rh Typing of the Patient: First, the laboratory performs full blood typing to identify the ABO group (forward and reverse typing) and the Rh status (positive or negative). For example, they conclude “This patient is B+” or “A−”, etc. It’s important to get this right as a foundation for the next steps.

- Selecting Compatible Donor Blood: The patient’s blood type is then used to choose donor blood units that are ABO/Rh compatible. Ideally, they will pick the exact same type for the transfusion (e.g., give an A− patient A− blood). If that exact type isn’t available, they will use the compatibility rules described earlier (for instance, O− blood can be given to almost anyone in an emergency, since it’s the universal donor type).

- Antibody Screen (Indirect Coombs Test): Often, the lab will do an antibody screen on the patient’s plasma. This checks if the patient has any unusual antibodies against other blood groups (beyond ABO/Rh). Note that ABO and Rh are the major antigens, but there are many minor blood group antigens (e.g., Kell, Duffy). If the patient has, for example, an antibody to one of these, the laboratory must ensure that the donor blood doesn’t have that antigen. (For Grade 8, it’s enough to know there are extra checks for other less common blood incompatibilities; you don’t need to memorize the other antigen names.)

- Crossmatching (“Trial transfusion” test): This is the final safety test before transfusion. In a crossmatch, the lab tech mixes a small sample of the patient’s plasma with a small sample of the donor blood cells in a test tube (or on a card). This simulates what would happen if that donor’s blood were infused into the patient, but on a small, controlled scale. The mixture is observed to see if any agglutination or reaction occurs. Cross-matching is a laboratory procedure used to assess compatibility. If the patient’s antibodies attack the donor cells in the test tube (i.e., clumping or other signs of a reaction), the donor blood is incompatible and will not be used. If there is no reaction in the tube, it’s a good sign the transfusion will be safe. The crossmatch serves as a final confirmation that the patient’s and donor’s blood are fully compatible.

- Transfusion: Only after all the above steps are clear does the actual transfusion proceed. Even then, the medical team will start the transfusion slowly and monitor the patient closely for any unexpected reaction.

These steps align with a hospital’s safety protocols. Determine the patient’s and donor’s blood group types and verify that they match. Modern blood banks also use computer systems to verify matches, but the crossmatch test is a crucial safety net – it’s the last defense against any mismatch that might not have been obvious from typing alone. (For instance, it can catch rare antibodies in the patient’s blood that weren’t part of routine typing.)

If there’s ever an extreme emergency where there isn’t time to fully type and crossmatch (say a patient is bleeding critically), doctors will use O-negative blood as an emergency supply, because O− is unlikely to cause an immediate reaction in any patient (no A, B, or Rh antigens). This is only done when absolutely necessary; otherwise, they wait for proper testing.

Connecting to Our Classroom Understanding: In class, we learned to determine ABO and Rh type using a tray, corresponding to step 1 above (forward typing and a basic Rh test). We also discussed how antibodies work, which relates to the idea of crossmatching (step 4) – you’re essentially checking whether the patient’s antibodies will attack donor cells. So, the science you learn in Grade 8 about antigens and antibodies is directly applied in the blood bank to design tests (Criterion B: Inquiring and Designing) that ensure a patient gets the right blood (Criterion A: Knowing and Understanding). By understanding these concepts, you could even design a simple experiment to simulate a crossmatch – for example, mixing two samples of known types to predict whether they’d be compatible.

Blood typing may initially seem like just memorizing A’s, B’s, and O’s, but it is a life-saving application of biology and chemistry. It combines an understanding of antigens and antibodies (scientific knowledge) with a clear procedural method (laboratory technique) to solve a real-world problem: how to safely share blood between people. In an IB MYP Science context, it’s a perfect topic to apply Criterion A (Knowing & Understanding) by learning why certain blood types can’t mix, and Criterion B (Inquiring & Designing) by exploring how we test and ensure compatibility.

By mastering blood typing, Grade 8 students not only learn about cell biology and immunology, but also appreciate the importance of careful experimental design and data interpretation. Whether in a forensic investigation (determining whether blood at a crime scene matches a suspect) or in a hospital emergency department (identifying the correct blood type for a patient), the principles remain the same. Blood typing is a concrete example of science that directly impacts human lives. It’s why a discovery from 1901 still matters every day: it enables transfusions to be performed safely, saving millions of lives worldwide.

So next time you hear about blood donors or a transfusion, you’ll understand the careful typing, matching, and cross-checking happening behind the scenes. It’s all about those tiny antigens and antibodies – a small difference that makes a big difference when it comes to saving lives.