The Interwar period in Bulgaria, spanning from the end of World War I in 1918 to the outbreak of World War II in 1939, was a time of profound change and challenge. The nation, burdened by the harsh terms of the Treaty of Neuilly, faced significant economic difficulties, political instability, and social upheaval. Amidst these challenges, Bulgaria sought to rebuild its economy, stabilize its government, and assert its place in the rapidly changing European landscape. This period also saw crucial military, infrastructure, and cultural developments, laying the groundwork for Bulgaria’s future trajectory.

Table of contents

Social Developments, Education, and Culture

During the Interwar period, Bulgaria experienced significant social changes, with educational developments, cultural revival, and shifts in population dynamics, all contributing to the nation’s evolving identity amid ongoing economic and political challenges.

Structure of the Population – Rural, Agrarian, and Urban

During the Interwar period, Bulgaria remained predominantly rural, with about 80% of the population engaged in agriculture. The urban population, though growing, accounted for only about 20% by the late 1930s. Urbanization was slow as industrial development lagged, and many rural residents continued to live in traditional village structures. The rural nature of the society influenced the social fabric, with smallholder farms dominating the countryside. However, land fragmentation due to post-war reforms led to economic challenges and limited the growth of commercial agriculture.

Migration – Internal and External

Internal migration during this period was characterized by a gradual movement of people from rural areas to urban centers, searching for better economic opportunities. However, this migration was limited, as economic conditions in cities were often no better than in rural areas. Externally, Bulgaria experienced significant emigration, particularly to the Americas and Western Europe, as economic hardships pushed people to seek better livelihoods abroad. At the same time, the influx of refugees from regions like Thrace and Macedonia added to the population pressures in Bulgaria.

Refugees to Bulgaria

The Treaty of Neuilly and subsequent agreements resulted in the displacement of approximately 500,000 Bulgarian refugees from Thrace and Macedonia. These refugees were resettled in various parts of Bulgaria, often in rural areas with scarce land. The government struggled to integrate these populations, leading to social tensions. The refugee crisis strained resources, but it also contributed to Bulgaria’s demographic homogeneity, as many of these refugees were ethnic Bulgarians.

Social Movements

The Interwar period in Bulgaria witnessed significant social and political unrest, particularly with the rise of communist and socialist movements. In June 1923, a military coup overthrew Prime Minister Aleksandar Stamboliyski, leading to his brutal assassination by the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO). The communist response culminated in the failed September Uprising of 1923, a nationwide rebellion against the new government led by the Bulgarian Communist Party.

The uprising, though widespread, was poorly coordinated and ultimately crushed by the government. The repression that followed was severe, with thousands of communists and sympathizers being arrested, and many were executed or died in violent clashes. The uprising and its suppression highlighted the deep divisions within Bulgarian society and the extent of the government’s determination to maintain control. The failure of the rebellion significantly weakened the communist movement in Bulgaria, leading to years of political repression and the near destruction of the Communist Party’s influence until World War II. The violence of 1923 left a lasting impact on Bulgarian politics, with the state’s repressive measures sowing the seeds for future unrest and radicalization.

Culture and Events

Cultural life in Bulgaria during the Interwar period was vibrant despite the economic challenges. The period saw a flourishing of Bulgarian literature, with writers like Yordan Yovkov and Elin Pelin depicting rural life and the struggles of ordinary people. In music, composers like Pancho Vladigerov gained international recognition. The government supported cultural development as part of a broader effort to promote national identity and pride, mainly through education reforms emphasizing Bulgarian history and culture.

Notable Buildings and Constructions from This Period

The Interwar period in Bulgaria was a time of significant architectural and infrastructure development. Sofia, in particular, saw a transformation as new buildings and public spaces were constructed. Sofia University Library (completed in 1928) became a key cultural and educational hub.

Significant buildings constructed during this period include the Ministry of Defense Building in Sofia, completed in the 1930s, and the Bulgarian National Bank headquarters, reflecting the nation’s modernization efforts.

Railroads and Infrastructure Expansion

The expansion of Bulgaria’s railway network was a significant focus of infrastructure development during the Interwar period. By 1935, the railway network had expanded by over 1,000 kilometers, connecting more towns and cities nationwide. Key routes included the Sofia-Plovdiv-Burgas line, which improved access to the Black Sea coast, and the Sofia-Vidin line, which enhanced connectivity with the Danube region. These projects were crucial for facilitating trade, supporting economic growth, and integrating the various areas of Bulgaria.

The road network also saw improvements, with new roads constructed to connect rural areas with major urban centers. By the late 1930s, Bulgaria had significantly improved its infrastructure, although financial limitations often slowed progress. The expansion of roads and railways was vital for the movement of goods and people, helping to modernize the economy and promote national unity.

These developments in architecture and infrastructure reflected Bulgaria’s broader efforts to modernize and assert itself on the European stage during the Interwar period.

Postwar Politics and Governments

The Interwar period in Bulgaria was marked by intense political upheaval, with frequent government changes, the rise and fall of influential leaders, and efforts to stabilize the country amid economic and social challenges.

Agrarian Union Policies

The Agrarian Union, led by Aleksandar Stamboliyski, dominated Bulgaria’s political landscape in the early postwar years. The Union’s policies focused on agrarian reform to empower the rural population, which comprised most of the Bulgarian populace. Stamboliyski implemented the Agrarian Reform Law of 1920, which redistributed large estates to smallholders, limiting land ownership to 30 hectares (300 decares). The goal was to create a class of independent small farmers who would form the backbone of the Bulgarian economy. The Union also promoted cooperative farming, establishing rural cooperatives to improve agricultural productivity and support smallholders.

Stamboliyski’s Foreign Policy

Stamboliyski’s foreign policy was characterized by a pragmatic approach to improving Bulgaria’s international standing following its defeat in World War I. He sought to reconcile with neighboring countries, particularly Yugoslavia, to secure Bulgaria’s borders and reduce the threat of further conflict. This led to the Treaty of Niš in 1923, where Bulgaria agreed to suppress IMRO (Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization) activities in exchange for improved relations with Yugoslavia. Stamboliyski also pursued closer ties with the Western powers and the League of Nations, hoping to gain support for Bulgaria’s economic recovery and territorial claims.

The Fall of Stamboliyski

Despite his efforts, Stamboliyski faced growing opposition from various factions, including the military, the monarchy, and nationalist groups like IMRO. His policies, notably the Treaty of Niš, were seen as a betrayal by those who sought the unification of all Macedonian territories under Bulgarian control. On June 9, 1923, Stamboliyski was overthrown in a coup orchestrated by a coalition of military officers, monarchists, and IMRO members. He was captured, tortured, and brutally murdered by IMRO militants, marking a violent end to his leadership.

Communist Uprising

In response to Stamboliyski’s overthrow, the Bulgarian Communist Party organized the September Uprising in 1923. The uprising attempted to resist the new government and establish a communist regime in Bulgaria. However, the rebellion was poorly coordinated and lacked broad support, particularly from the peasantry, who had benefited from Stamboliyski’s land reforms. The government, under the leadership of Aleksandar Tsankov, quickly crushed the uprising with brutal force. Thousands of communists and sympathizers were arrested, and many were executed, leading to a period of severe repression and the near destruction of the communist movement in Bulgaria.

The Tsankov and Liapchev Governments

After the coup, Aleksandar Tsankov took control, leading a repressive government that sought to stabilize the country through authoritarian means. His regime was characterized by martial law, political repression, and censorship. In 1926, Tsankov was succeeded by Andrey Lyapchev, who pursued a more moderate approach. Lyapchev’s government focused on economic stabilization, including securing a loan from the League of Nations to help manage Bulgaria’s war debt and stabilize the currency. Despite these efforts, the government remained authoritarian, with limited political freedoms.

The Crises of the 1930s

The global Great Depression profoundly impacted Bulgaria, exacerbating existing economic difficulties. Agricultural prices plummeted, leading to widespread rural poverty and discontent. The financial crisis also heightened political instability, with frequent changes in government and growing social unrest. The situation was further complicated by the rise of fascist and nationalist movements, which capitalized on the economic and social discontent to gain influence.

Foreign Policy in the 1930s

Bulgaria’s foreign policy in the 1930s was shaped by the desire to revise the Treaty of Neuilly and regain lost territories. The government, particularly under Tsar Boris III, sought to align Bulgaria with powers that could support these goals. Initially, Bulgaria maintained a policy of neutrality, but as tensions in Europe grew, it increasingly leaned toward the Axis Powers. Despite this alignment, Bulgaria balanced its relations with neighboring countries to avoid conflict.

Evolution of the Liberal and Conservative Parties

Liberal Party Evolution

The Liberal Party in Bulgaria, which had dominated the political scene in the late 19th century, began to decline in influence during the Interwar period. The emergence of the Agrarian Union, which drew significant support from the rural population, and the rise of the Communist Party, which attracted the working class and disenfranchised groups, eroded the Liberal Party’s voter base. The Liberal Party struggled to maintain relevance as it failed to address the pressing economic and social issues of the time.

Conservative Party Evolution

The Conservative Party, traditionally representing the interests of the monarchy, landowners, and the military, also declined during the Interwar period. Its influence waned as the political landscape became increasingly dominated by new forces, including the Agrarian Union and the growing appeal of socialist and communist ideologies. By the 1930s, the Conservative Party’s role had diminished significantly, with many of its members joining other political coalitions or shifting their allegiance to support Tsar Boris III’s authoritarian regime.

Impact of the Agrarian and Communist Parties

The Agrarian Union, led by Aleksandar Stamboliyski, primarily drew its support from the rural peasantry, which had traditionally supported the Liberal Party. The Agrarian Union’s focus on land reform and rural interests resonated with these voters, significantly weakening the Liberal Party. Meanwhile, the Communist Party attracted urban workers and intellectuals disillusioned with the Liberals and Conservatives, further diminishing their influence.

Formation of the Democratic Alliance

The Democratic Alliance was formed in 1923 as a response to the political turmoil following the fall of Stamboliyski. It was a coalition of conservative, liberal, and nationalist elements that sought to stabilize the country and counter the influence of the Agrarian Union and Communist Party. Key figures in the Democratic Alliance included Aleksandar Tsankov and Andrey Lyapchev. The Alliance gained power following the 1923 coup and was dominant in Bulgarian politics during the late 1920s and early 1930s. However, its inability to address the economic crises of the 1930s and internal divisions weakened its position over time.

Key Dates and Shifts

- 1920: Agrarian Reform Law passed by Stamboliyski’s government, solidifying the Agrarian Union’s power.

- June 9, 1923: Coup against Stamboliyski, leading to the rise of the Democratic Alliance.

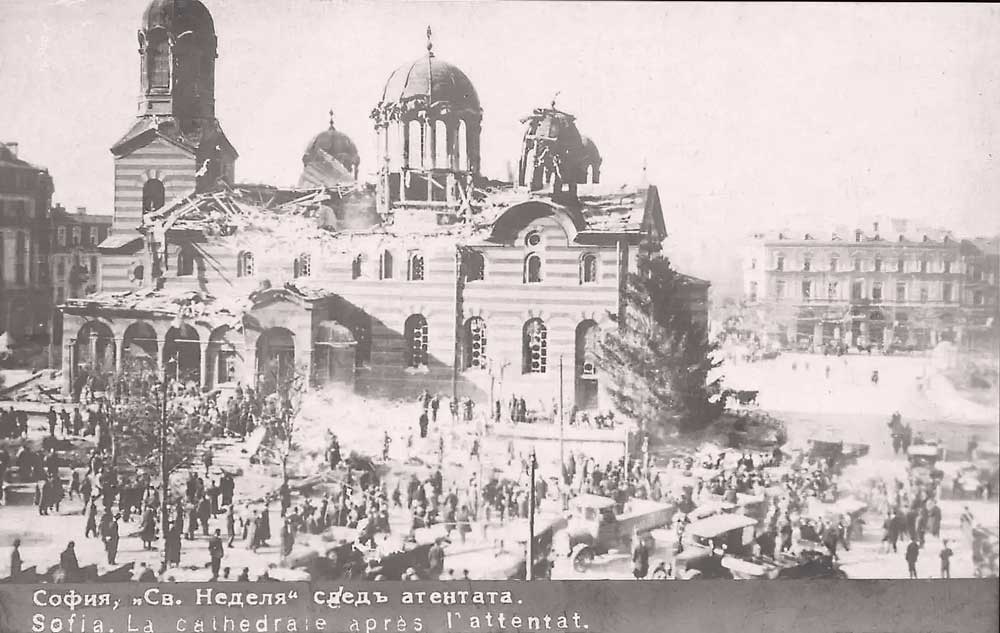

- 1924-1925: Communist Uprising and subsequent repression under Tsankov’s government, including the April 1925 bombing at Sveta Nedelya Church in Sofia, where a failed assassination attempt against the government led to severe reprisals against communists. St. Nedelya Church Today.

- 1926-1931: Andrey Lyapchev’s government represented a more moderate approach within the Democratic Alliance.

- 1931: Elections bring a coalition government to power, marking a shift towards greater political diversity, although instability continued.

- 1934: Military coup by the Zveno group, marking the end of traditional party politics and the rise of Tsar Boris III’s royal dictatorship.

Elections and Governments

The period between 1923 and 1940 saw several elections and frequent changes in government. The struggle between the Agrarian Union, the Communist Party, and conservative forces dominated the political landscape. Elections were often marred by violence, voter intimidation, and fraud. Notable elections include the 1927 election, which solidified the dominance of Andrey Lyapchev’s government, and the 1931 election, which saw the rise of a coalition government led by the Democratic Alliance. Throughout the 1930s, political instability continued, with frequent shifts in power and increasing authoritarianism under Tsar Boris III.

The Role of the Monarch

King Boris III played a pivotal role in Bulgaria during the Interwar period, using diplomacy and strategic alliances to maintain stability and navigate the country through political challenges.

King Boris III’s Leadership

King Boris III’s leadership was marked by a strategic and diplomatic approach to foreign policy, particularly during the turbulent 1930s. Following the chaos of World War I and the Treaty of Neuilly, Boris III prioritized restoring Bulgaria’s international standing. He skillfully navigated Bulgaria’s foreign relations, aligning cautiously with neighboring countries and major European powers.

In the early 1930s, Boris sought to strengthen ties with Italy and Germany, recognizing their growing influence in Europe. His efforts to align with these nations were evident in Bulgaria’s accession to the Balkan Pact in 1934, a defensive alliance to stabilize the Balkans. However, Boris remained wary of fully committing to any power bloc, understanding the risks involved.

During the global economic crisis, Boris III’s diplomatic engagements helped secure favorable trade agreements, particularly with Germany, which became Bulgaria’s primary trading partner. By the late 1930s, Bulgaria had effectively aligned with the Axis Powers, although Boris maintained a degree of independence. Notably, he resisted German pressure to declare war on the Soviet Union, reflecting his cautious diplomacy and concern for Bulgaria’s long-term interests.

Further, Boris III’s foreign policy achievements were also seen in his efforts to resolve territorial disputes peacefully. His pragmatic approach helped Bulgaria regain Southern Dobrudja from Romania through the Treaty of Craiova in 1940 without resorting to military conflict. This success bolstered his popularity and reinforced the monarchy’s authority during widespread instability in Europe.

Royal Involvement in Political Affairs

Under Boris III, the monarchy played a central role in stabilizing Bulgarian politics during periods of crisis. Boris frequently intervened in political affairs, particularly during times of governmental instability. For instance, after the military coup in 1934, which brought the Zveno group to power, Boris III maneuvered to diminish their influence and restore the monarchy’s authority gradually.

By 1935, Boris III had established a royal dictatorship, bypassing traditional party politics and ruling through a controlled parliament. During this period, the king exerted significant influence over government appointments and policy decisions to stabilize Bulgaria during economic and political uncertainty.

Boris III’s involvement in political affairs was not without controversy. While his actions helped maintain order, they also suppressed political pluralism and entrenched authoritarianism. However, his popularity among the nation remained relatively high, partly due to his efforts to protect Bulgaria from the worst excesses of the political turmoil that characterized much of Europe during this period.

The Role of the Church

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church played a vital role in shaping the nation’s identity during the Interwar period, providing spiritual guidance and preserving cultural heritage amid political and social changes.

Influence of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church

During the Interwar period, the Bulgarian Orthodox Church was central to national life and pivotal in shaping societal values, education, and national identity. Following the national trauma of the Treaty of Neuilly, the Church provided spiritual support. It helped maintain a sense of continuity and resilience among the Bulgarian people. The Church’s influence was decisive in rural areas, where it was often the leading institution providing guidance and cohesion.

During this period, significant developments in the Church included the canonization of St. John of Rila in 1925, an event that reinforced national pride and spiritual unity. The Church also saw the restoration of key religious sites, such as the Rila Monastery, a symbol of Bulgarian Orthodoxy. The Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Sofia, completed in 1924, became a national symbol representing religious and national identity.

Key figures during this time included Exarch Stefan I, who led the Bulgarian Orthodox Church from 1945 to 1948, and Metropolitan Neophyte, who was influential in the church’s educational and cultural activities. Their leadership helped the Church navigate the challenges of the period, including the rise of secular ideologies and the political instability of the 1930s.

Church-State Relations

The relationship between the Bulgarian Orthodox Church and the state was marked by cooperation and mutual influence. The Church supported the state’s efforts to maintain social order, particularly under the reign of King Boris III, who saw the Church as a crucial ally in promoting national unity. The monarchy provided financial support to the Church and upheld its authority in religious and educational matters.

A key event highlighting this relationship was the dedication of the Shipka Memorial Church in 1934. The church symbolizes the Russo-Bulgarian friendship and reminds Bulgaria of its liberation struggle. The Church also legitimized government policies, particularly during times of crisis, such as the global economic downturn of the 1930s.

However, the Church also faced challenges, particularly from the rise of communist and socialist movements, which were often critical of religious institutions. The failed communist uprising of 1923 and subsequent repression saw the Church align more closely with the state, as both sought to counter the influence of leftist ideologies.

Overall, the Bulgarian Orthodox Church remained a stabilizing force during the Interwar period, playing a critical role in preserving Bulgaria’s cultural and religious identity while maintaining a close relationship with the state. This period saw the Church continue its mission of spiritual leadership, even as it navigated the complexities of a rapidly changing world.

Interwar Economy

The Interwar economy in Bulgaria focused on stabilizing the nation after World War I, managing debt, modernizing infrastructure, and supporting agriculture and industry despite significant challenges.

Economic Policies

During the Interwar period, Bulgaria’s government, particularly under Prime Minister Andrey Lyapchev (1926–1931), implemented policies to stabilize an economy severely affected by World War I. By 1924, inflation had reached alarming levels, dramatically rising prices compared to pre-war levels. Bulgaria faced a significant national debt, primarily due to reparations imposed by the Treaty of Neuilly. The Lev Stabilization Act of 1928 was a critical measure that aimed to control inflation and stabilize the currency, setting a fixed exchange rate. Despite these efforts, Bulgaria remained economically vulnerable, especially during the global Great Depression, which further strained its recovery.

Banking Sector

During the Interwar period, Bulgaria’s banking sector underwent significant development, with the Bulgarian National Bank (BNB) continuing to play a central role in managing the nation’s finances. The BNB and newly established state-owned banks like the Bulgarian Agricultural Bank (BAB) provided crucial financial services to the population. The BAB was particularly important in addressing the credit needs of the rural population, offering loans to farmers at a time when the agricultural sector was vital for Bulgaria’s economy.

In addition to state-owned institutions, the period saw the rise of private banks. By 1911, there were 58 private banks in operation, with a total capital of 45 million levs, 30% of which was foreign investment. Despite the presence of foreign banks like Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas and Deutsche Bank, their contribution to financing the domestic industry was relatively limited. These banks primarily focused on servicing the government’s foreign loans and providing credit for import-export activities rather than supporting internal economic growth.

Development of Agriculture, Infrastructure, and Trade

During the Interwar period, Bulgaria focused heavily on revitalizing its agriculture, which remained the backbone of the economy. By the 1920s, approximately 80% of the population was engaged in agriculture. The Agrarian Reform Law of 1920 redistributed land, benefiting over 200,000 smallholders but leading to fragmented landholdings, which hindered large-scale farming.

Subsequent governments prioritized infrastructure development, particularly in transportation. Between 1920 and 1935, Bulgaria expanded its railway network by over 600 kilometers, enhancing trade routes domestically and with neighboring countries. Significant projects included the Sofia-Plovdiv railway and the modernization of port facilities in Varna and Burgas, boosting Bulgaria’s trade capabilities.

Trade policies focused on increasing exports of agricultural products, particularly tobacco, which accounted for nearly 50% of Bulgaria’s exports by 1930. However, the global Great Depression of the 1930s severely impacted trade, leading to a 30% decline in export revenues between 1929 and 1933. Despite efforts to diversify, the economy remained vulnerable to fluctuations in global markets.

Taxation and Fiscal Changes

In response to the severe financial challenges after World War I and the reparations mandated by the Treaty of Neuilly, Bulgarian governments, particularly under Prime Minister Andrey Lyapchev, implemented several significant taxation reforms. The Agrarian Reform Law of 1920 increased taxes on land, targeting properties over 30 hectares, which affected wealthier landowners. By 1923, land taxes had risen by 25%. Additionally, customs duties were increased by 15%, and excise taxes on essential goods like tobacco and alcohol saw a 10% hike. These measures aimed to generate revenue for debt repayment and economic stabilization.

Despite these efforts, the increased tax burden led to widespread dissatisfaction. The higher taxes, ongoing reparations payments, and the global economic downturn placed immense strain on the population, particularly in rural areas. Economic hardships exacerbated social tensions, leading to unrest and opposition against the government’s fiscal policies.

Debt Positioning, Loans, and Banks

Bulgaria’s national debt soared during the interwar period, primarily due to war reparations and the need to finance reconstruction. By 1923, Bulgaria’s public debt had reached over 3 billion levs, with foreign debt making up nearly 80%. The Bulgarian National Bank (BNB) played a central role in managing these debts, securing loans from international banks such as Deutsche Bank and Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas.

In 1926, the Bulgarian government negotiated a stabilization loan of 1.5 billion levs from the League of Nations to restructure the economy and repay outstanding debts. This loan was instrumental in stabilizing the lev and controlling inflation, although it came with strict conditions, including international experts overseeing Bulgarian finances.

Learn more about debt and its impact on Bulgaria’s foreign policy.

Reparations, Indemnities, Repayment

The Treaty of Neuilly imposed severe reparations on Bulgaria, initially amounting to 2.25 billion gold francs, payable over 37 years at a 5% annual interest rate. This burden was later reduced in 1923 to 550 million gold francs, payable over 60 years after Bulgaria negotiated a reduction citing its limited ability to pay.

Bulgaria made payments totaling 173 million gold francs by 1922 and continued to service its reparation debt until 1932. Following the Lausanne Conference, Bulgaria’s reparation obligations were abandoned mainly due to its economic difficulties, though the country remained under financial strain from the remaining debts.

Military Developments

Following the devastation of World War I, Bulgaria faced severe restrictions on its military capabilities due to the Treaty of Neuilly in 1919. The treaty reduced the Bulgarian army to just 20,000 troops, focusing on border defense and internal security. Despite these constraints, Bulgaria initiated significant reforms to modernize and restructure its military forces. The army was reorganized into compact, efficient units, including infantry, cavalry, and artillery divisions. Particular emphasis was placed on maintaining a well-trained and disciplined force that could be rapidly mobilized.

Military Equipment

During this period, the Bulgarian military primarily relied on infantry weapons like the Mannlicher M95 rifles, manufactured by Steyr in Austria, and Maxim machine guns, produced by Vickers in the UK. These weapons, remnants from World War I, were still adequate for Bulgaria’s defensive needs. In terms of artillery, Bulgaria maintained its arsenal of Krupp cannons, initially acquired from Germany during World War I. The military took steps to modernize and sustain these artillery pieces to ensure their effectiveness.

Bulgaria’s military aviation was modest but showed growth during the Interwar period. The Bulgarian air force fleet included aircraft such as the Dewoitine D.27 fighters and Potez 25 bombers, primarily sourced from France. By the late 1930s, the air force had expanded to include Bristol Blenheim bombers and Dornier Do 11 transport aircraft. These additions marked a significant step in establishing a more capable and modern air force.

Military Leadership

Military leadership during this period was crucial in guiding these developments. General Nikola Zhekov, a prominent figure from World War I, continued to influence military reforms. Colonel Damyan Velchev, a key figure in the Military League, played a significant role in the 1934 coup and subsequent military activities. His leadership was instrumental in reorganizing the army and promoting a more modern military doctrine. General Ivan Valkov, who served as Minister of War during the early 1930s, was responsible for substantial military reforms and rearmament programs that prepared Bulgaria for potential conflicts in the late 1930s. These leaders’ efforts were pivotal in ensuring that, despite restrictions, Bulgaria maintained a capable and strategically positioned military force.

Final Words

The period between the liberation and the end of World War II, often called the Third Bulgarian State, was marked by significant transformation and struggle in Bulgaria. Emerging from the devastation of World War I, the country grappled with the immense challenges of economic recovery, political instability, and social change. Efforts to stabilize the nation during this time set the stage for Bulgaria’s involvement in the complex and turbulent events leading up to World War II. As Bulgaria navigated these years, it planted the seeds of future conflicts, ultimately positioning the nation for its eventual involvement in the global upheaval of World War II.

References and Sources

- Jelavich, Barbara. History of the Balkans, Vol. 2: Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press, 1984.

- Crampton, R.J. A Short History of Bulgaria. Cambridge University Press, 1984.

- Crampton, R.J. A Concise History of Bulgaria. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Lampe, John R. The Bulgarian Economy in the Twentieth Century. Croom Helm, 1986.

- Bell, John D. Peasants in Power: Alexander Stamboliyski and the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union, 1899-1923. Princeton University Press, 1977.

- Pundeff, Martin V. Bulgarian Nationalism, in Sugar, Peter F., and Ivo J. Lederer. Nationalism in Eastern Europe. University of Washington Press, 1969.

- Nedelchev, Lyubomir. The Role of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church in Shaping National Identity during the Interwar Period. Sofia University Press, 1940.

- Post-war Economies (South East Europe), 1914-1918 Online International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Growth without Development: The Post-WWI Period in the Lower Danube. Perspectives and Problems of Romania and Bulgaria, 1920. Read more

- “Bulgaria: A Country Study,” Library of Congress, 1989. Read more