Why Writing Matters in Science

Writing isn’t just an extra task in science – it’s how you show what you learned. A grand experiment means little if you can’t explain it. In fact, writing a science report helps you organize your thoughts and share your findings, and it pushes you to be precise about scientific ideas. Writing about science can even strengthen your understanding: it improves your scientific reasoning and clarity of thinking. Whether you’re doing a lab or an essay, good writing skills turn your work into knowledge that others (and you) can use.

Lab Reports: The 6-Part Structure

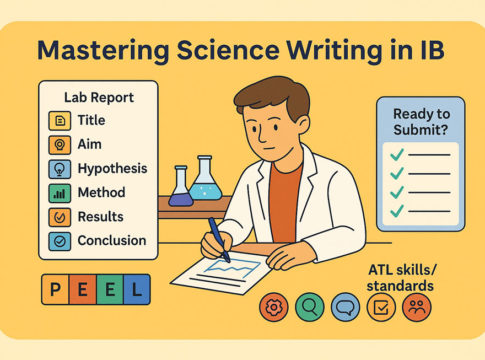

Illustration: Overview of a lab report’s six parts – Title, Aim, Hypothesis, Method, Results, Conclusion (each with a distinct icon).

A lab report is a structured way to record and communicate your experiment. In IB sciences (and science classes in general), a typical lab report includes Title, Aim, Hypothesis, Method, Results, and Conclusion. Here’s what each part means:

- Title: A short, descriptive name for the experiment. It should reflect what you investigated. (Example: “The Effect of Light Intensity on Plant Growth” is more apparent than “Biology Lab #1.”)

- Aim (Purpose): What question or goal are you investigating? This is a brief statement of why you experimented – essentially your research question or objective.

- Hypothesis: Your predicted answer to the question. What do you think will happen? Write a testable prediction (with a reason if possible). For example, “If light intensity increases, then plant growth will speed up,” because you expect more light = more photosynthesis.

- Method: The steps you took to experiment. Include materials, variables, and procedures in a clear, logical order. Someone else should be able to repeat the experiment from this section. Write in the past tense (and usually passive voice) as an objective record of what you did.

- Results: What you observed or measured. This section presents data – often tables, graphs, or observations. Keep it factual: don’t explain or interpret the data here (save that for later). Make sure to label tables/graphs with units and titles so they’re easy to understand.

- Conclusion: What do the results mean, and did they answer the aim? Summarize your findings and state whether they support your hypothesis. Please explain briefly why you got those results and what they imply. You can also mention trends, uncertainties, or real-world implications. A firm conclusion links back to the purpose and says what was learned. (In more advanced reports, this is paired with a “Discussion” section analyzing errors and improvements – but for a quick report, you can combine the analysis in the conclusion.)

Investigation Reports: Inquiry Question, Variables, Data, Analysis, Evaluation

Not every science write-up is a formal lab report. Sometimes you’ll do an investigation report – for example, an IB Internal Assessment or a science fair project. This is less about a pre-set lab and more about designing your own experiment. Key components include:

- Inquiry Question: The driving question or problem you’re investigating. This is like the aim in question form. Please make it clear and focused (not too broad). For example: “How does water pH affect seed germination rate?” This question guides everything in the report.

- Variables: Identify your independent variable (what you change), dependent variable (what you measure), and controlled variables (constants you keep the same). Clearly outlining variables shows you designed a fair test. (E.g., independent: water pH, dependent: germination percentage, controls: same seed type, temperature, light, etc.)

- Data: The observations and measurements you collect. In an investigation report, present your data clearly in tables or graphs. Include units and descriptive titles. If you have a lot of raw data, you might put it in an appendix, but be sure to summarize key results in the report.

- Analysis: This is where you interpret the data. Look for trends or patterns (e.g., “Seeds in neutral pH sprouted faster than in acidic or basic solutions.”). Do calculations (averages, percentages, maybe even statistical tests) to make sense of the results. Discuss whether the data answers your question and how it relates to scientific concepts.

- Evaluation: Reflect on the experiment’s quality and what it all means. Discuss errors or uncertainties and how they might have affected the results. Importantly, consider how confident you are in the conclusions. Suggest improvements: What would you do differently to get better data or to explore further? Finally, connect back to the inquiry question – did the experiment resolve it, or are there open questions? This evaluative thinking shows you truly understand your investigation (and it’s often a separate section in IB reports for scoring).

Extended Response (Essay-Style): Using PEEL to Structure Paragraphs

In science classes, you might also write longer responses or essays – for example, answering an exam question in a few paragraphs or writing an extended essay. Here, clarity and argument structure matter. A handy writing tool is the PEEL method for paragraphs:

- Point: Start with a clear topic sentence. State the main idea or argument of the paragraph (your point). This should directly answer or address the essay question.

- Evidence/Example: Next, support your point with evidence – a fact, data, or example. In science writing, this could be a short quote from a text, a reference to a study, or data from an experiment. The evidence supports your statement and lends it credibility.

- Explain: After giving evidence, explain how it supports your point. Don’t assume the reader will infer the connection. Spell out why this evidence is essential: e.g., “This data shows a clear increase, which means…”. This analysis shows your understanding.

- Link: Finally, link the paragraph back to the overall question or your larger argument. This closing sentence ties your idea into the bigger picture or leads to the next point. It keeps your essay focused.

Using PEEL ensures each paragraph is focused and logical – great for scientific explanations. For example, suppose the question concerns the effects of climate change. In that case, one paragraph’s Point might be about rising temperatures, you’d give Evidence (a statistic or study), explain its significance (impact on ecosystems), and then link back to the question or lead into the next effect. This structure makes your writing clear and persuasive.

Tip: In any science essay or extended response, always connect your evidence back to the main claim. Don’t just dump facts – explain why they matter. And use proper terminology, but in a way a fellow student could understand.

ATL Skills in Science Writing

Approaches to Learning (ATL) skills aren’t just buzzwords – they’re the skills that make you a better learner and a better science writer. When writing lab reports or essays, you actually practice many ATL skills:

- Thinking Skills: Critical thinking is huge in science writing. You analyze data, identify patterns, and draw conclusions. You also use creative thinking to design experiments or explain concepts in new ways. For example, evaluating an experimental method or determining why an anomaly occurred demonstrates higher-order thinking.

- Research Skills: Writing in science means you might need to gather background information, cite sources, or compare findings with literature. Knowing how to find reliable scientific information (and reference it) is key. Citing a source for your introduction or using a known theory to justify your hypothesis are good applications of research skills.

- Communication Skills: Obviously, writing is communication! This includes organizing your report clearly, using scientific vocabulary appropriately, and even choosing the right graph to present data. Communication skills also cover knowing your audience – writing an explanation a peer can understand, for instance, rather than copying complex text from a journal.

- Self-Management Skills: A well-written science report often reflects good self-management. Planning your work (e.g. designing the investigation, then setting aside time to write it up), meeting deadlines, and proofreading your own work are all self-management. Keeping a lab notebook and turning it into a structured report takes organization and perseverance.

- Social Skills (Collaboration): Yes, writing can be collaborative, too. In labs, you might work with a partner or team – sharing data and ideas before each person writes their own report. Peer editing is another collaborative aspect: asking a friend to review your draft or giving feedback to someone else. Using polite, constructive feedback to improve scientific writing is a great social/communication crossover skill.

By developing these ATL skills, you don’t just write better reports – you become a more independent and effective learner in science. For example, being organized and analytical will help not just in one lab, but in any research task you tackle in the future.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Even good students slip up in science writing. Here are some common mistakes and how to avoid them:

- Copy-Pasting Instructions or Sources: Don’t just copy your teacher’s lab handout or a website into your report. It’s obvious and doesn’t show your understanding. Lab instructions are NOT written in report style, so you must paraphrase and write the method in your own words. Always aim to write in a way you understand and could explain aloud.

- Missing the “Why”: A report with results but no explanation is just half done. Avoid simply listing data without analysis, or giving a conclusion without reference to the hypothesis. Always tie it back to the science concept or question. (For example, why did you get those results? Did they support the hypothesis? What do they mean in context?) Leaving out this discussion will cost you points.

- Using Vague Terms like “human error”: Be specific about errors or uncertainties. Writing “human error” doesn’t tell the reader anything. Instead, say “We might have measured the length inaccurately because the ruler was worn” or “The solution temperature may have dropped during transfer, affecting the reaction rate.” Specifics show you understand what happened and how it impacts results.

- Claiming you “proved” something: Science rarely proves a claim absolutely. Saying “I proved my hypothesis” is a red flag. It’s better to say “The results supported the hypothesis” or “did not support” it. This shows you grasp that one experiment supports or refutes an idea without declaring ultimate proof.

- Poor Structure or Presentation: Another mistake is failing to follow the expected format or writing messy sections. For example, mixing up where you place information (such as discussing results in the Method section) can confuse readers. Also, watch out for unlabeled figures or tables, no units on numbers, or sloppy grammar/spelling. These make your report hard to read. Always double-check that each section has the right content and that your data is clearly presented (with labels, units, titles) – clarity counts!

- Informal Language or Personal Reflections: While you should write in a natural, clear way, avoid colloquial language, texting abbreviations, or diary-style comments. Phrases like “I learned a lot” or “this was cool” are too informal for a formal lab report. Stick to objective descriptions in reports, and save opinions for reflection sections if required. Essentially, write in a scientific tone: clear, concise, and objective.

Quick Checklist: “Ready to Submit?”

Before you turn in that lab report or science essay, run through this quick checklist. It can save you from easy mistakes:

- All sections included? (For labs: Title, Aim, Hypothesis, Method, Results, Conclusion – each clearly labeled. For essays: proper introduction, body, and conclusion structure.)

- Was the data presented clearly? Tables and graphs are titled, labeled (with units), and referred to in the text—no raw data lingering without context.

- Analysis done? Did you explain what the results mean and link back to the hypothesis or question? (No unexplained numbers or “floating” quotes.)

- Conclusion answers the question? Make sure your conclusion actually addresses your aim or inquiry question and says if the hypothesis was supported. It should feel like a satisfying wrap-up, not a dead end.

- Language check: Spelling and grammar reviewed? Scientific terms spelled correctly and used in the right way? (Tip: the word “data” is plural – e.g., “the data were recorded,” not “was”.) Write in the past tense for methods and use a formal tone.

- Citations/References done (if needed)? If you used information from other sources (books, websites, etc.), did you cite them in the text and list them at the end? Avoid plagiarism by giving credit.

- Formatting & guidelines: Lastly, ensure you met any specific requirements (word count, format, font, etc.). Little things like line spacing or naming conventions can matter if your teacher provided guidelines.

If you can check off all those boxes, then take a deep breath – your science write-up is ready to shine! Good luck, and remember that every report or essay is a chance to improve your science communication skills. Keep writing, keep experimenting, and you’ll keep getting better.